2013: The Year Social Games Grew Up

They came into the world like screaming babes, vying for our constant attention and garnering the coos of neighboring strangers. For lack of a better term, “social games” like FarmVille latched onto our existing networks and wouldn’t let go: The weaning child was hungry, their grip strong. These games sought a new kind of reverence from their players, a need to soak up not only your time but those of acquaintances, co-workers, and high school buddies. They were good at feeding addiction and manipulating our loyalties. They weren’t all that good at being games.

But now the child has grown. What began in infancy has matured; we now have games built out of an increased understanding of the way we move through our always-on world. They don’t beg and plead for our and our friends’ attentions; instead, they build a sense of community. On their own, disconnected from the masses, they’d still be compelling. Let us call them Social Games 2.0. Like teenagers, problems still exist. But the needle has moved. They can survive on their own. The big evolution here, the reason to celebrate? That Social Games 2.0 are games at all.

To create something new, the old must first be eradicated.

We find this growth in unexpected places. The Simpsons Tapped Out acknowledges the shift while at the same time hewing to its forebears’ inescapable tendencies. During the opening cutscene, we see Homer at his nuclear powerplant job ignoring the flashing red lights at his desk, signifying catastrophic danger, for the flashing lights on his tablet’s brain-draining Elf Town app, signifying worthless rewards. We’re supposed to see Zynga’s FarmVille and laugh (or shed a tear or two) in recognition. When the plant explodes, taking Springfield with it, we’re left with a barren field and our hapless donut-loving hero to prod into rebuilding his life. The image fits: To create something new, the old must first be eradicated.

Yet Social 2.0 games don’t start anew so much as build onto pre-existing territory, like Tapped Out and its blatant, self-aware aping of Zynga’s world-builders. The first time I played Supercell’s Clash of Clans, I was struck by how immediately familiar everything felt, until realizing I was basically playing Warcraft 2. In 1997, if you had told me the game I was playing on my PC with friends everyday after school would, in fifteen years, be playable on my phone—and not only that, but would be connected to every other person playing this shrunken war sim—I would have laughed over the sound of my whirring 28.8 modem.

Clash of Clans still relies on some of mobile’s necessary footholds, with buildings built and soldiers trained over time (shortcuts available—at a price), but the foundation is strong enough to weather our attention’s attrition. There’s even something like verisimilitude here: Rome was not built in a day, nor should your clans become strong with a few finger taps. The time or money spent becomes part of the game, a challenge to overcome. Even at its most surface level, Clans is a beautiful game: stirring animation, well-drawn art, the primal satisfaction of defending your land and attacking an enemy’s stronghold. Remove the reward cycle of FarmVille or its ‘Ville descendents and what’s left is barren, silent: All that was ever really there was the clicking.

It’s not the games that need evolving, but the players.

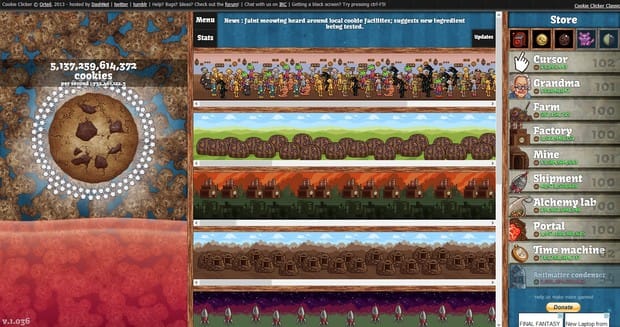

Ian Bogust’s Cow Clicker sunk its udders into the phenomenon when the designer and game theorist created an app that left the underwire bare for all to see. The motive and result were the same: You are here to click. Even his pointed satire couldn’t escape the centripetal force of mobile’s social whirlpool; the “game” was a massive hit. More recent examples Candy Box and the nefarious Cookie Clicker continue this trend of experiments made accidentally whole. Their success reveals a most unsettling truth: That it’s not the games that need evolving, but the players.

Until we’re ready, there’s plenty on which to cut our teeth. Social Games 2.0 abound: Triple Town mates the simple Match-3 formula with resource management and forest critters for a charming, cerebral time-sink. The world-beating Candy Crush Saga out-duels the reigning champ Bejeweled with a refined dripfeed of serotonin and rainbow power the likes of which haven’t been seen since Peggle. GungHo’s Puzzle & Dragons is sweeping through Japan like Mothra’s radiated breath, destroying all comers with its mix of collectible monsters and surprisingly nuanced strategy. The studios behind these improved mobile games have noticed each others’ efforts: GungHo has bought (alongside Softbank, a Japanese tech firm) 51% of Supercell, makers of Clash of Clans.

In their original state, social games’ life span was that of a dust mite. They burned too hot only to flare out.

Will 2.0 plus 2.0 equal 4.0? Only the future knows. The present is a graveyard of past supernova hits; when Zynga bought OMGPop, the studio behind Draw Something, the Pictionary-lite was a phenom, the It Game. Less than eighteen months later, a tiny fraction of its audience remained and the studio was shuttered. In their original state, social games’ life span was that of a dust mite. They burned too hot only to flare out. To survive, Social Games 2.0 have needed to evolve, become more sustainable than their fragile origins. Less reliable are the wavering loyalties of an audience spoon-fed more and more choices each day.

As social games mature, so will the players who tend to them, like an Empty Nester must deal with renewed independence as their once-little one goes off into the world. For now, Social Games 2.0 are still reliant on us, and we on them. But the newborn, that screaming malformed alien, has filled out, resembling more closely what it was always meant to be. We see patches of ourselves peeking through. We want to see them grow up. What happens next? If the stereotypical teenager storyline is true, get ready for a rocky patch of rebellion, dismissiveness and experimentation. Sounds fun to me.