A model for referencing videogames in literature

Generally when literature alludes to other media—Facebook, texting, film, the song “Hey, Soul Sister” by Train—my first reaction is to cringe. At its worst these mentions feel unnatural, lazy—the author’s gawky attempt to connect to the modern world or to an artistic tradition by simply referencing it. But even good media references can be jarring. Haruki Murakami’s thoughtful incorporation of jazz and classical music into his work, for instance, still has a weirdness to it.

Perhaps this can be pinned down to degrees of separation from reality. When reading a work of fiction, it is typically odd to see mentions of real-world media, because we then have to reconcile the fact that this media exists in a fictional world as well as reality. The fiction no longer exists within its own self-contained bubble, but rather one with the same kinds of consumable culture that we interact with every day in real life. That realization is a lot for the reader to take in.

The problem is that literature needs to be more contained than reality. Things cannot happen at random or without consequence. Events, dialogue, and narration need to connect to the greater thematic elements of the work. They need to serve a purpose. Otherwise, why are we reading?

Alex Gino’s George is a young adult novel centered around the eponymous ten-year-old trans girl. It reads like an analogue to Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Just as Blume’s work concerns Margaret’s cisgender experience of settling into her identification as a young girl, so Gino’s work concerns George’s parallel trans experience.

A quick word on George as a novel. I’m always apprehensive about “coming out” queer literature because authors tend to either martyr their protagonists for moral purposes or else make the narrative so unbelievably optimistic that it is difficult to connect to on a personal level. George, thankfully, is neither. It leans toward the optimistic, but within a more believable context. There are no strawmen villains, nor are there people who accept George at first reaction without question. It is written for queer young adults rather than the parents of queer young adults—a novel meant to show these young people that they aren’t alone, rather than help those parents process the young person’s plight. By this I mean that Gino doesn’t condescend to George; they treat her point of view with respect, on an equal level. And that really makes all the difference with queer young adult literature.

I’m always apprehensive about “coming out” queer literature

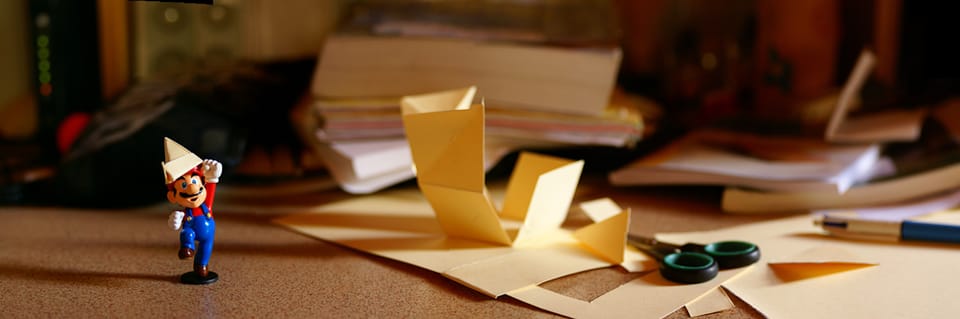

Now, George has one particular passage that shows exactly what well-implemented media references look like. This passage involves our titular character playing Mario Kart with her brother Scott. Although extremely different people—Scott is a stereotypically gross teen boy, unwilling to shower regularly, obsessed with gory horror movies and violent first-person shooters—they are able to bond over playing this videogame together.

The passage begins with Scott, in an uncharacteristically mellow mood, invites George to play Mario Kart with him. It establishes the current state of Scott and George’s relationship, suggesting that they used to spend a lot more time together.

“Scott hadn’t asked George to play video games in months. They used to play almost every day. George would come home after school to find Scott on the couch, watching wrestling and ignoring his homework. They would play until Mom got home and yelled at them to turn off the TV and get their homework done. Now Scott usually came home just in time for dinner, if not later.”

From here the two play the game together, enjoying the competition and the camaraderie. The ensuing passages work well because they smooth Scott and George’s relationship over, illustrate how they can get and have in fact gotten along despite how opposed their personalities are. Gino describes how they laugh together, work together to defeat the computer opponents and compete against each other in jovial sibling rivalry. This makes the coming reaction that Scott will experience regarding George’s identity much more believable.

But Gino doesn’t use Mario Kart solely as a device to show the unspoken affections shared between the two. They take it a step further by actually having the characters that George and Scott play as reflect and deepen their development. Whereas Scott chooses the bulky, brusque and evil Bowser, George selects Toad. To quote:

“She liked the happy sounds the little mushroom made. When she was alone, she sometimes drove as the princess, but she didn’t dare choose her in front of Scott.”

These character choices further enforce the dichotomy between the two characters, reveal how drawn toward femininity George is, and how drawn away from masculinity. This is pushed further by the final paragraph of the chapter, in which Scott persuades George to switch the a first-person shooter. George is quickly bored with the game, unenthused by its macho violence. Without condemning masculinity or violent games outright, Gino stresses their character’s repulsion from such stereotypically male attributes, emphasizing George’s feminine inclinations.

YA authors are fond of referencing media, perhaps as a way to foster a love of culture in its readers. But it often doesn’t feel organic. John Green is guilty of this, for instance referencing Gabriel García Márquez’s The General in His Labyrinth in Looking for Alaska. The character Alaska has many great works of literature on her bookshelves, General among them. References to General are apparently meant to connect Alaska to García Márquez’s philosophical musings. While not misguided, the connection feels forced, in essence borrowing literary import to beef up Alaska‘s message. Green’s references to General neither invite more character development nor bring much to the table aside from the name of an interesting novel. It is a barely veiled literary device used to make Alaska appear deeper than it is.

references media as a means to develop characters and their relationship

George instead references media as a means to develop characters and their relationship with one another. George is able to incorporate media into its story without using it as just another literary pretension, without the sense that the author is making lazy attempts to try to connect to the modern world. It is a natural-feeling occurrence of media within George‘s fictional world, one whose perfect sense and intelligent implementation prevents it from jarring the reader.

In the scheme of George, this Mario Kart section is a quiet interlude within the larger story. Yet it speaks volumes about the character of George and the dynamics in her home. That is why it works so well as a media reference. Without bringing too much attention to itself, making sure to make perfect sense within the context of a suburban child’s life, Mario Kart operates as a helpful tool to further articulate the author’s fictional world.