A people’s history of PlayStation Home

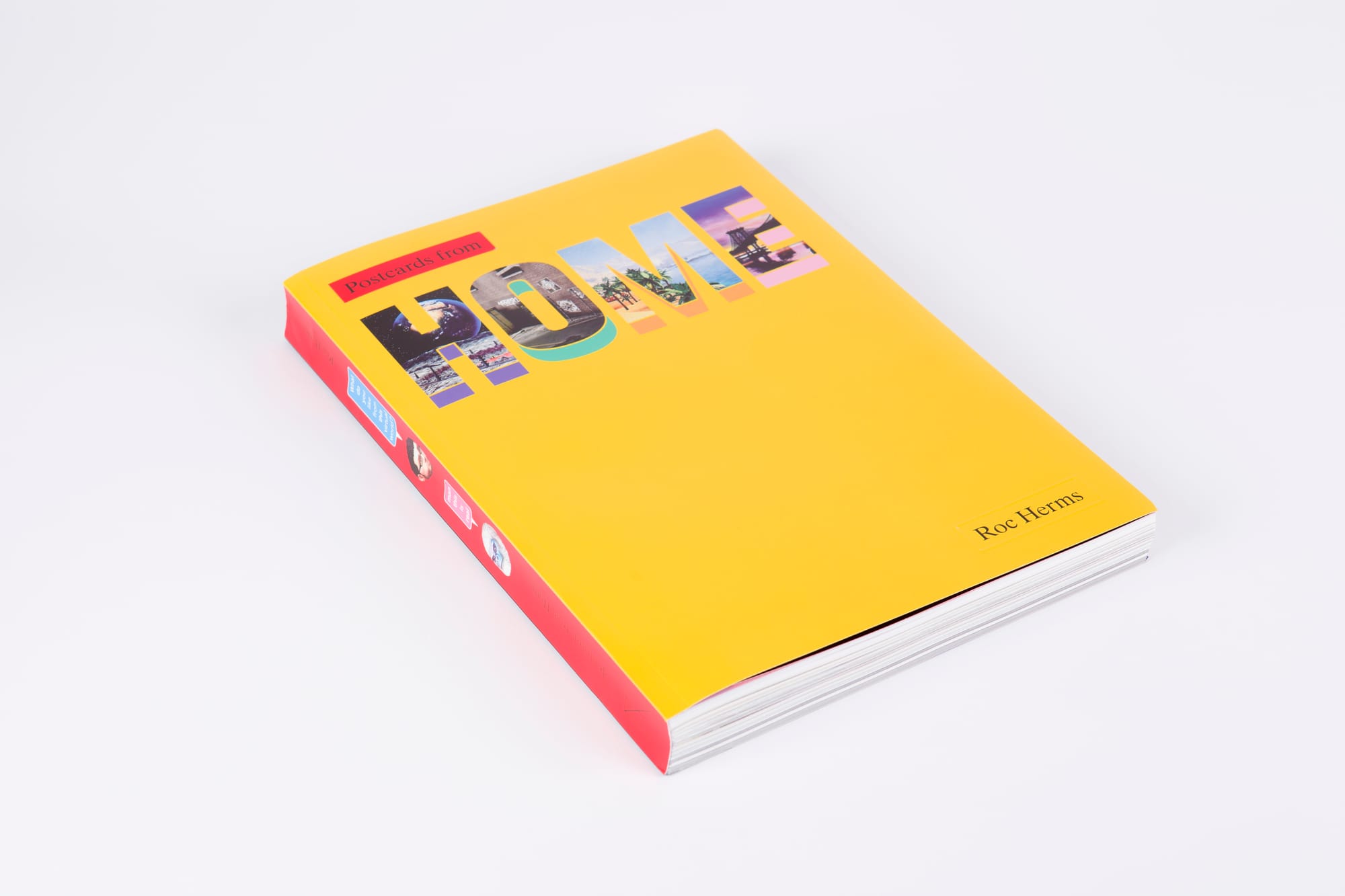

Released at the end of last year, Postcards from Home has the feel of a curio: a weighty tome assembled exclusively from images captured within Sony’s discontinued virtual world, Home (2008-2015). Its author, the Spanish photographer Roc Herms, has explored games before, whether making absurdist use of the Game Boy camera or documenting an enormous LAN party from the perspective of the hardware. But it only takes a few pages for the scope of Postcards from Home to reveal itself as something much more empathetic, even human, full of penetrating longform interviews that explores the digital architecture of Home as well as the emotional lives of the people filling it. The result is something like embedded reporting within a virtual world, assembled into a frequently moving graphic novel that doubles as a people’s history of a dying world.

Perhaps befitting of an exploration of digital space, Postcards from Home is a playful physical object, riffing on paperstocks and page layouts, and the imperfections of an in-game camera. In one passage on the afterlife, Herms utilizes a soft, transparent paperstock, making each frame fade into the next; later, an honest-to-god centerfold flips out of the book. I spoke with Herms from his home in Barcelona about the years-long process of constructing the book, as well as transhumanism, Facebook, and his infiltration of the cult-like Homelings.

Kill Screen: Let’s talk about how you started the book. Which came first: You getting into PlayStation Home or you starting the book?

Roc Herms: The book is quite autobiographical. In the beginning of the book, there’s a history between me and Alex, my best friend. His nickname is aBeBoy. He was living in Barcelona, but then there was one winter where he got a girlfriend in Madrid and he went to live in Madrid. On weekends, we spent many hours with me on my sofa and him on his sofa with headsets and microphones playing Call of Duty, playing Minecraft (2011). [We stayed] together inside different kinds of virtual worlds and online games. Not just playing, but talking about, “How was your week, your day?” etc.

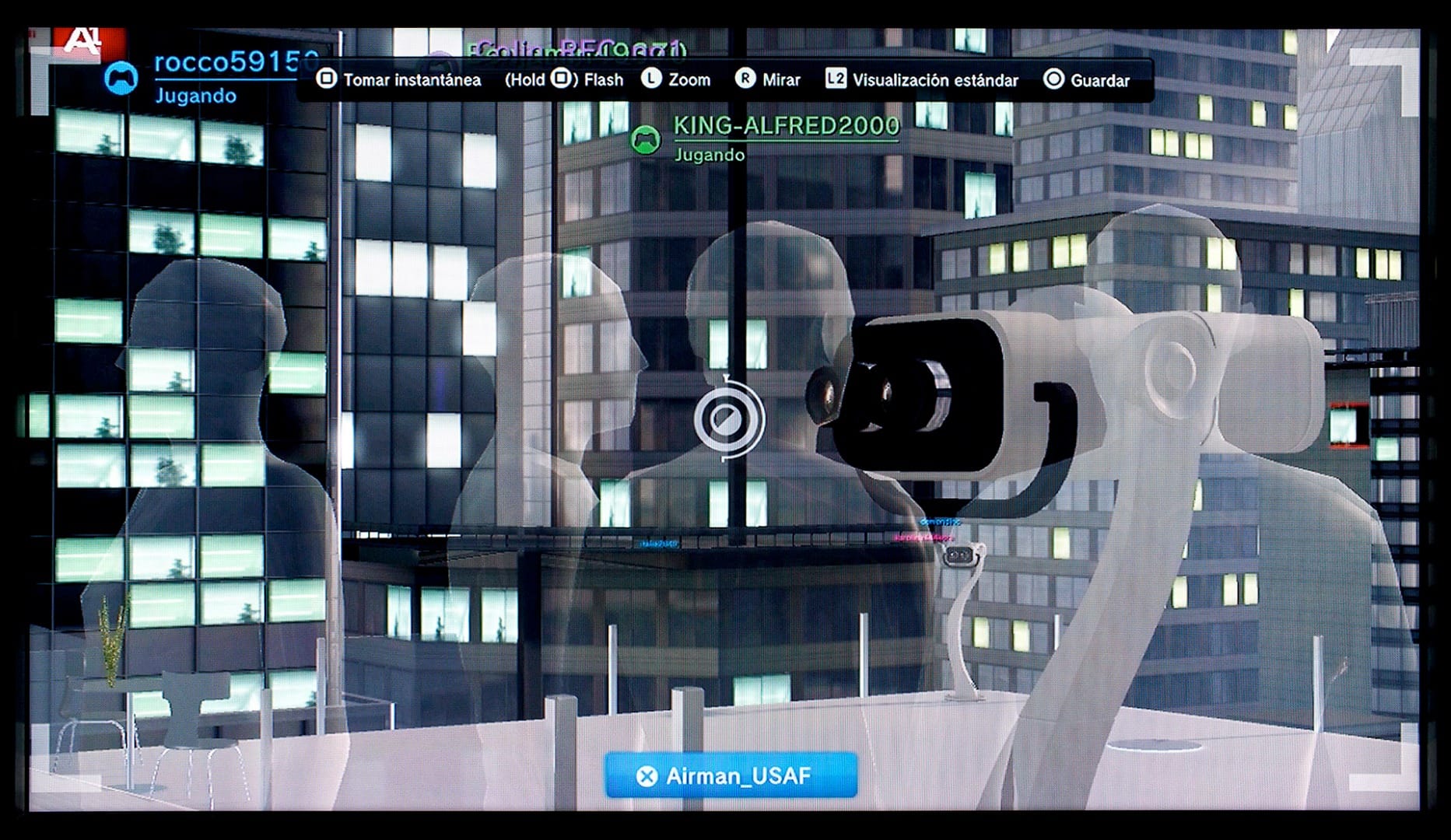

At some point, more or less at the time, I realized that all those 3D environments—where I have control of the movement of the character and the point of view—[provided the two variables] I needed to be able to work as a photographer. You can move around, you can look, and then whenever you want, you can take a screenshot and capture what you’re seeing. I [did go online] on New Year’s Eve, we made a dinner [inside] Home, and I realized that there were many people celebrating with New Year’s Eve displays. And it was like “Woah, that’s not a game, there’s people doing important things for them [in here].” I thought: “Now I may as well try to document the lives of those people that are standing inside this place.” That was the beginning.

KS: What year was this New Year’s Eve experience?

RH: 2010. 2009 to 2010. At the beginning, I was just walking around and taking pictures. And then one day I realized that in this place, when people talk, you don’t hear the conversations because that will be so messy in a public environment. But conversations are displayed at the top, and I was holding in my hands the only camera able to capture those conversations. I could be in a place and I could not just be looking, but seeing what people were saying. Maybe the most important thing for me was finding the pictures of what people were saying to each other.

KS: How did people respond in interview?

RH: In the beginning it was like “Can I take your picture?” and many people said no. Then there was one of them that said, “Yes, okay” and then I took a picture. I was telling them that I was a photographer in real life—well, now I don’t like to use that word, “real,” because maybe [it would make too much of a] distinction between physical and digital. I did learn that both of them are “real” in a way. Things happen in [PlayStation Home], relationships can be “real” in [its virtual] streets [as they are] in a physical environment.

KS: What’s the big difference between using a traditional physical camera and the one inside PlayStation Home?

RH: I got into photography quite late, when digital cameras arrived and almost everyone became a photographer. In the beginning, I was using it as an excuse to travel with my parents—I left them at the hotel. But little by little, I started to use photography to learn about histories or make small projects to go with my work. And I focus on subjects that interested me before photography. I grew up with a Game Boy and Super Nintendo, making LAN parties with my friends. I always related to videogames and computer technology.

I have another book that [physically looks] like a laptop. I’ve been documenting a huge LAN party in Spain, something around 8,000 people are connected for a week, and they spent a full week inside this place. The idea is to travel from the black to the inside of the computer. The idea that the black is where it starts in a way, and then closer to the screen it’s like collecting all the desktops of the people that were there. That was the first project. That ran for five years.

KS: You spent five years on that book and then five years on this one?

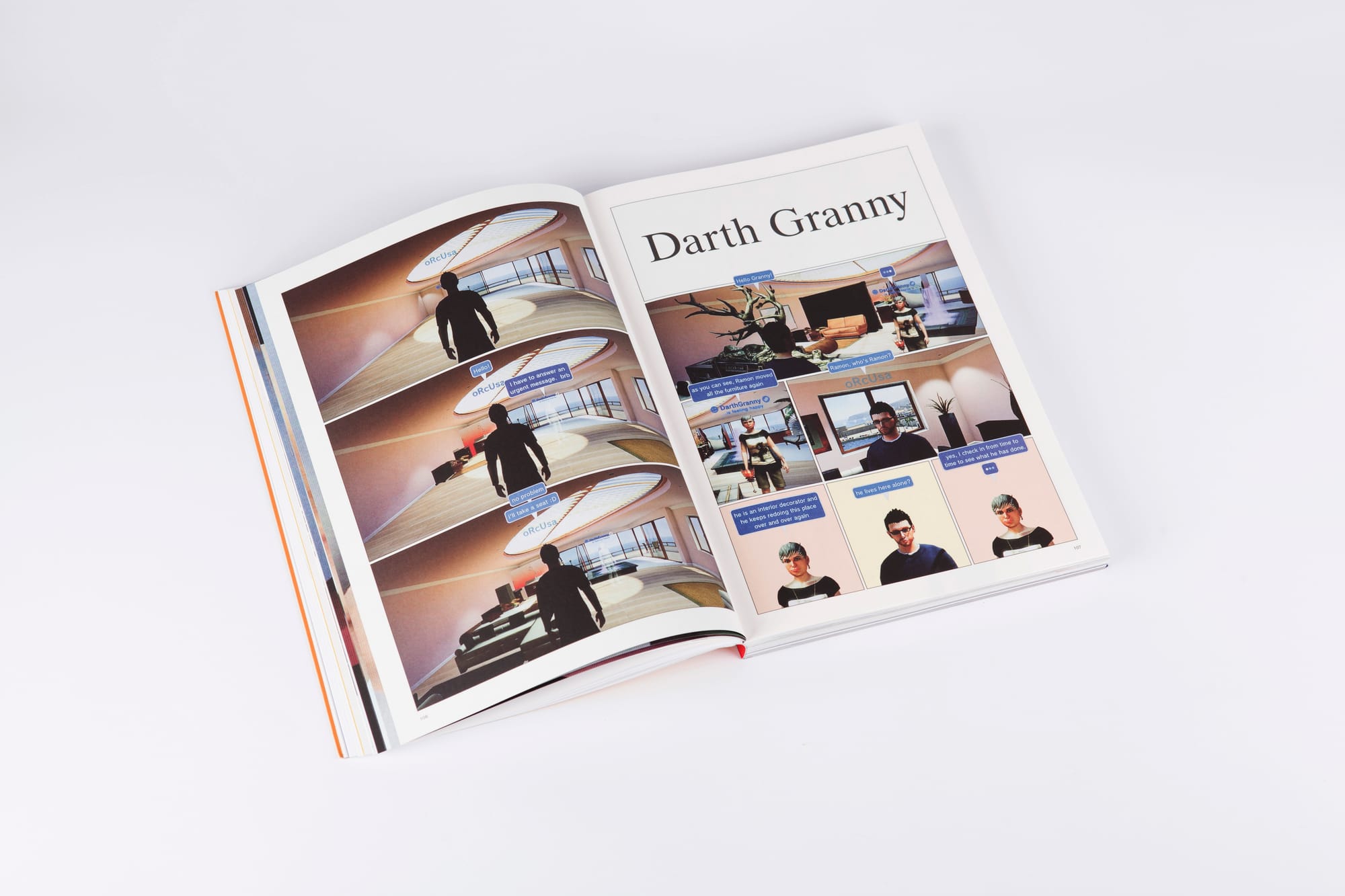

RH: Same time, or less. Five to six. When I realized that I was making this book of interviews, when [it came to putting] them on paper, I thought I could use a comic book or graphic novel style. In graphic novels, you go, you write, and then you mix it. And here, the words and the graphics come at the same time. Graphic novels in a sense are always fiction. And this is like, the same. [It was right in that] moment of time and space, and there was a lot of work on design, putting things on the pages.

KS: One thing that sticks out in Postcards from Home is how you spent a long time talking to a person’s avatar, and then sort of shockingly cut to an image of the person from the real world. How did those moments come about?

RH: I often thought of how much to include the physical reality. Actually, there’s this chapter of [a user named] Joanna Dark where she loves fashion and she wears all different stuff. For that, I thought “oh, maybe I can go to United States, and [try to portray her] with all the clothes that she has in the physical world.”

In the end, it was like, maybe I don’t need to include their physical lives. I think the first one is all grainy from Hawaii. There’s a [very old] picture of a [young woman], after I’ve shown all her avatars. One time I asked if I could have a picture of her, and she sent me this old picture, telling me that if I want to see one picture of her, she would like to show [her younger self]. But, right now, maybe she doesn’t feel comfortable with her physical appearance. [She talked] about identity and how in these places you feel detached from your physical body.

KS: The next real-world picture is of you, on vacation, when PlayStation Network was shut down.

RH: Yeah, like four years ago, the servers were down for like 52 days. At the time there was a disconnection. But the idea of my built wall was shut down, because the servers were down. So it’s time to go into the physical world and enjoy some sun and mojitos, etc.

KS: Toward the end you infiltrate a group called the Homelings. It has an ideology, a uniform, and even a leader named Mother. They say they’re not a cult, but they do admit that they look a lot like a cult. And then you show a real-world picture of Mother, who is a member of the US military. Did you talk to her in-game?

RH: I talked to Mother in a chat on the forums they have outside of Playstation Home. But she was on duty—I’m not sure exactly where—and I could not interview her properly. But I did talk a lot with her that in a way was like Jesus Christ. Like, there’s God and there’s Jesus Christ, everyday they’re just organizing a lot of stuff. But no, no I could not talk to Mother much.

KS: What drew you to the intersection between the digital and physical worlds?

RH: It’s the interest to learn. I can play online games for a long time, but they will always be games. They’ll be quick, running and shouting from one to another. Maybe I did not realize before this project, that when we were inside Quake (1996), that we would actually be living inside Quake. We would be sitting in front of the screen, but my mind was inside that wall, and we were being chased. You could be scared, you could be happy. I connected to Second Life (2003) when it was on top, but I did not make it anywhere there, and I did not understand what people were doing in there.

I think also that maybe while writing the book, with almost everything having happened inside of Home, it made me think of virtual worlds in general. I was thinking about where this kind of stuff can go in, I dunno, 20 or 50 years. And I think, in the end, everything is in the hands of the program. In Playstation Home, for example, it’s for all ages, and you will not see naked [bodies] or sex, as it’s deleted. But afterwards, I checked and there are some virtual worlds that have sex—I mean, during the process I did study [a few of the other] virtual worlds. And it also made me read about science, and how maybe one day you will be able to disconnect your physical senses and connect to digital ones. Maybe we will be able to connect and disconnect from the digital and physical. Then the next step is maybe trying to reach a point where intelligence will be restored like human life. Maybe we will be able to live inside one of those kind of environments.

I did learn that both of them are “real” in a way

KS: What did you do when Home closed? I guess was it about a year ago.

RH: Yes, more or less, one year ago.

KS: What were you doing?

RH: I was in the process of designing the book, and from the beginning I knew that Home was gonna die some day. I was lucky for it to be exactly when the book was finished, because I think it’s a nice ending for the book. But in the beginning, I knew that those lifespan of those environments was very short, because technology advances at such an incredible rate and speed. When the PlayStation 4 came out, all the people in Home went away, so they decided to close it. So when Home died, I was in the process of doing the book and it was like, “Okay, now I have a proper ending.” The last page of the book is the last frame of one of the last parties that were being held inside the world before the pop-up message that said, “Unable to connect to the server.”

KS: What were you doing specifically when it happened?

RH: Actually, I had a very long day. And after all those years of going inside and after knowing that that was an important day, that maybe I could have stayed there in the party, and make another short chapter from it, I did not connect that day. Because I had traveled with my girlfriend and I already knew that there would be many people recalling this event. And I thought to explain it in the book I could use the people who there to actually show it.

I think inside Home itself, I didn’t really make any friends, [not] any real friends, [no] personal attachments with which to connect. I would go inside to work and learn, but I wasn’t connecting in Home that matched. Actually, I think that Playstation Home was not the most interesting virtual world of recent times. There are others that are more interesting. But this one gave me all the tools I needed to work as a photographer. This single thing about seeing what people were saying in such a graphical and direct form, was much better than what was offered in Second Life.

KS: What other virtual worlds do you think are more interesting than Home? Are you involved with any of them?

RH: I think the next step is Facebook. Maybe it’s not a 3D environment where you can build your house and buy a nice sofa, etc. But it’s a digital environment where all of us are living a huge part of our lives. It’s a place where I can work, where I can meet people. I think that social networks, in a way, are like an escalation of those online 3D worlds.

In Spain, today, we spend about seven and a half hours in front of a computer—for me it’s more, of course, and for my mother less, I guess. But I think that when we stay in front of the computer, we are inside the computer. We still have to connect. When I’m sitting here, I can be working, I can be talking to someone. And I think everything is going on inside this 2D environment on the screen. I think that everyone is spending a lot of time of their life already working, socializing, or living inside the Internet or this digital world. Other examples could be Minecraft, or World of Warcraft (2005), or Eve Online (2003).

KS: Something you get at in the book is that Home was like a big shopping mall. A consistent part of the experience was consuming stuff. How did that strike you as a space to live in? When I’m in a shopping mall, after a while I start feeling claustrophobic, I wanna get out. What did it feel like to live there?

RH: At the beginning, after New Year’s Eve, and after working around there a bit, I thought it was quite difficult to find someone to do something interesting, because it’s more focused on shopping. But afterwards I discovered that, even with those restrictions, I found two proper people in this place. One of those is the guy who writes for a magazine and spends four hours a day inside Home, socializing with his friends, but then spends another four hours writing for a magazine that talks about this environment. In a way, it’s almost like living inside this place, because his work and his friends are in this place.

But maybe one thing is that with Second Life, for example, you have to access it through your computer. And maybe the people who were into that were more nerdy or geeky [than the console players of PlayStation Home]. I think Sony sold around 50 million units [of the PlayStation 3] worldwide or something. Maybe many people that didn’t know anything about these types of virtual worlds had found Home by accident, because it was already connected on the console. Like the grandma from Hawaii, for example, she told me that she never knew about any of this, and her grandson was playing one day and she found it by accident. Maybe it opened up this environment to people who didn’t know anything about it before.

KS: So you found that people’s naivety counteracted the commercialized nature of the space?

RH: Even being in a place more focused on shopping, they wanted to try you to do this stuff. [But] they did not give you as many tools as other places, where you can construct things, you can build things; it was a limited space. But as I write in the book, people saw through the restrictions and managed to construct things of their own. They found their own way to enjoy the place.

KS: Yeah, the Homelings were a very interesting example of that. They created a culture around specific things that you can consume, like having an outfit you were supposed to wear.

RH: The beginning of the Homelings, Mother joined when the beta was out, when there was only the one stage—it was the bowling alley. At the bowling alley there was this machine, that if you beat the game they give you this outfit, and then you have to beat the machine to dress like them. The idea of the Homelings was more or less this one. [Despite being located] in just one stage, they managed to construct a group of people, or friends, of more than one thousand. And they had their own rules and their own culture.

people saw through the restrictions and managed to construct things of their own

KS: What are you working now that Home is gone?

RH: After a long travel inside the digital world, I got a big motorcycle, and I’m now leaving my apartment in Barcelona. From Barcelona I’m going to the Middle East, and then I don’t know where we’ll end up going. My plan right now is to get away from keyboards for some time and watch the mountains.

I’m pretty sure that if I end up in Kazakhstan, or some kind of away-from-keyboard country, that I will still have my eyes on how the people there relate with technology. Maybe there will be some projects for me to [pursue] there that talks a little bit about the use of technology in another environment. I will not make a project about the flowers of Kazakhstan, I’m pretty sure.