During the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado I handed out American flags to important people.

You know how the camera pans over the audience during a large convention and everyone is holding up the same sign or flag and you’re at home thinking, “Did these people come with those flags? How does everyone have the same sign?” Well, it’s thanks to people like me. Those flags help to create good optics. In the world of politics, optics is a catch-all phrase which roughly translates into, “How does this play on camera?”

I’ve just returned from my first Electronic Entertainment Expo, better known as E3, where optics of a different kind were on display.

Badges and Lanyards

If you ever want to see how power and class structures in a society operate, hand out badges. No. Hand out lanyards with badges attached to them.

The badge represents more than just physical access to a location. It represents someone’s devotion to a cause, their life’s work, and ultimately, their acceptance into a community of like-minded individuals.

People love their badges, often holding them tenderly

This past Tuesday, as I walked a few blocks to the Los Angeles Convention Center to pick-up my own badge, I noticed the brightly-colored lanyards and badges flapping in the wind. People were wearing their E3 badges blocks from the convention. I smiled to myself. I remember passing out badges to community members at the field office in Golden, Colorado. People love their badges, often holding them tenderly. I’m no different. My 2008 DNC badge is packed away in a dark drawer. I don’t display it because I’m afraid it will get sun-faded.

When someone puts on a badge a number of physical changes occur: they stand a bit taller and their chests puff out just a bit more. They belong, and now no one can tell them otherwise because they have the proof dangling from their neck.

As I waited in the badge pick-up line outside of the South Hall of the Los Angeles Convention Center, I took out my printed confirmation sheet and handed over my California State ID to security. I watched my badge as it was printed out and placed in a protective plastic pocket.

As the security personnel handed my badge to me he said, “Have a great show!”

I nodded enthusiastically, ‘Yeah, YEAH! I will have a great show,’ I thought.

I placed the lanyard around my neck and repressed the urge to take the requisite “here’s me with my badge on” photo, instead opting to read the list of rules and regulations on the back of the badge.

The entire ceremonial presentation of a badge makes you feel just a little bit important. But, as I’ve come to find out, you’re only as important as your badge indicates.

Convention organizers are methodical folks. What may at first glance appear to be a merely decorative element is likely there to aid in speedy identification.

Red at the bottom? Oh that’s press. They are press. I am not press.

Wait, why is their badge orange? Does my badge have orange? Why isn’t mine orange, what does orange mean?

This damn sticker, what does this sticker mean? Should I be worried about this sticker?

Badges invoke an unspoken social transaction between people. First, someone identifies the markings and symbols on the badge and then, if further inspection is required, the person will go the additional step and read the person’s title and name.

The badge allows everyone to avoid the social niceties of “Who are you? What do you do?” Instead it allows for the question mostly everyone at these events cares about anyway, which is “What can you do for me?”

Carpeting

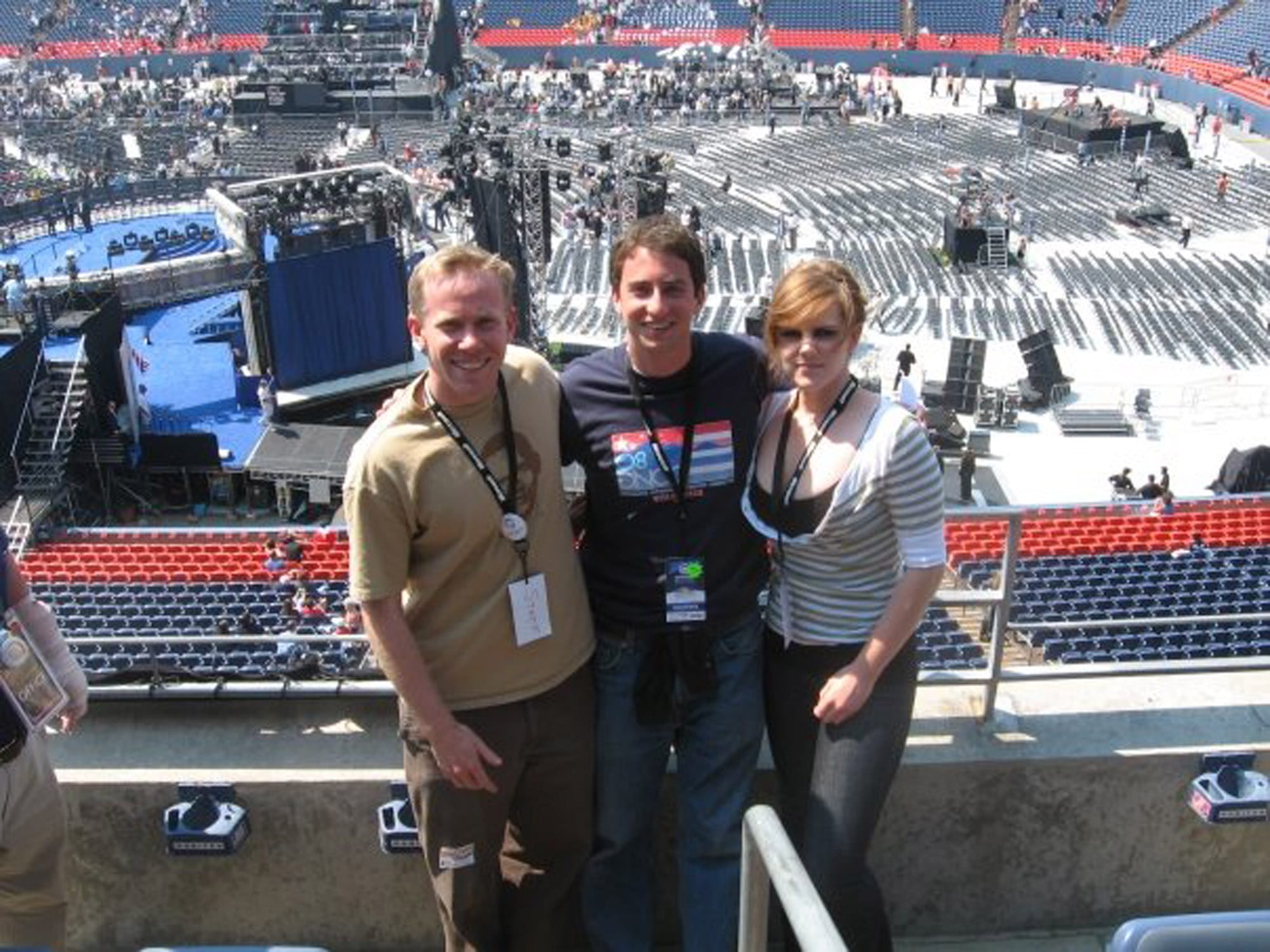

On August 28, 2008, I walked onto Invesco Field, where the final day of the DNC would be held, and I was overwhelmed. The sheer size of the space, the effort that had gone into transforming it was on a scale the likes of which I had never seen. The space would ultimately hold 84,000 cheering people.

Being overwhelmed is an important part of any convention. It’s supposed to feel larger than life, and in this E3 wildly succeeded.

I walked through the giant glass doors of the south hall and saw this:

Again, I found myself taken aback by the spectacle of it all. I made my way up the stairs of the towards the exhibit space itself. Security glanced at my badge and ushered me inside where I was bombarded with lights, sounds, and people walking in every possible direction. Banners and displays towered above me.

Most convention floors are either cement or cement covered with the sheerest possible suggestion of carpeting. The presence of plush carpeting is a luxury of a significance that should not be overlooked.

Blue carpeting at the DNC was there to indicate where the VIPs were located. There are different levels of VIP, but these were the VIPs who wanted (or needed) to be seen. So the visually identifiable VIPs were to sit on the blue carpeting, in the padded chairs.

After spending most of my day standing on concrete, I had somehow ended up near the VIP section, where the bottom of my foot brushed against the supple blue looped-fiber carpet. “This is it,” I thought to myself, “This is what it means to have arrived.”

The major game publishers at E3 clearly understood this. They had upgraded from the standard convention floor covering to some of the plushest pile carpeting my foot has ever had the privilege of stepping on. It was a subtle reminder to all those present who had the extra money to spend, and who didn’t.

Swag

As I continued to meander through the hallways of E3 I noticed people had started to accumulate swag. Back in 2008, when I ran out of flags, people were furious with me.

“What’s the real reason you don’t have any more flags?”

“Why does that person over there have a flag and I don’t? Shouldn’t everyone have a flag?!”

Humans possess within them a special reserve of anger for the precise moment they are denied swag.

their social equity is elevated thanks to the convention bump

Still, just before a convention someone, somewhere, will ask what the purpose of swag is and whether it is worth the added expense. Convention veterans already know the answer to this question: Of course it is.

Swag helps people form personal connections. It’s a tangible, physical reminder of their participation and unlike a badge (which everyone is obligated to wear) swag is unique, limited, and is therefore a prized and coveted status symbol.

Lapel Pins

The lapel pin is nearly ubiquitous in the field of politics but also by any person looking to indicate some level of influence and authority. Never underestimate the power a carefully placed lapel pin on a shirt or blazer.

Lapel pins are all about impression management—it’s how people at conventions engage in the presentation of self. The pin says, “I want you to know I am a part of this very big thing but I am not defined by it.”

These pin-wearers never stay in one place for too long. They walk purposefully from one end of the convention hall to the other, usually with one or two other people. Those people are buffers who protect the pin-wearer from the general public. Your existence will not be acknowledged unless they know you, or unless their minders whisper in their ear that you are someone they should know.

All of this is done to position the individual above the plainclothes attendees or branded t-shirt-wearing booth workers. These people want you to know—they need you to know—that they are ready at a moment’s notice to partake in a meeting or a business deal.

Press

The relationship any organization has with the press can usually be summed up as tenuous but necessary. Each media outlet paid as much deference as their influence and reach allows.

I’ve always thought about press at conventions as being treated like a neighbor who you don’t really fancy but want to be on friendly terms with because they make really good cookies. Every holiday season you get a box of those cookies and you don’t want to find out what it’s like to not get a box of those cookies. So you treat them kindly and respectfully, and maybe you plow their driveway when it snows a few inches, but not anything substantial. Certainly, nothing that would indicate that you are all actually friends.

So, the press have their meetings with the lapel-pin people, while the branded t-shirt wearers herd the crowd and work the convention floor. Deals are made, pitches are pitched, and attendees are sufficiently swagged out.

At conventions, people whose names are rarely spoken by those passing by on the street become de facto celebrities. Everyone wants to be seen with them and for a few days their social equity is elevated thanks to the convention bump or, in political terminology, the big mo’ (momentum).

Conventions aren’t about a political candidate or a particular video game, they are about crafting messages and creating narratives which can be sold or voted for.

I know all of this, yet still I am drawn to them, to places where people, for all their disparate reasons, find themselves united by something larger than themselves.