Playing Aban Hawkins & the 1001 Spikes is a bit like watching Bill Murray relive Groundhog Day. The protagonist replays the same scenario over and over. Each guy wants to impress someone (just replace Andie MacDowell with an absent father) and both dudes start out pretty confused. But things start to get clearer after a few reruns. Over time, repeated attempts bring new realizations, and through repetition they each get the chance to improve. Eventually, recurrence becomes a gift, a way to understand what it is that they are supposed to do. Over numerous relivings, Bill Murray and Aban Hawkins learn to navigate a familiar environment with precision. Through that process, they achieve progress, and, in the end, reach something close to perfection.

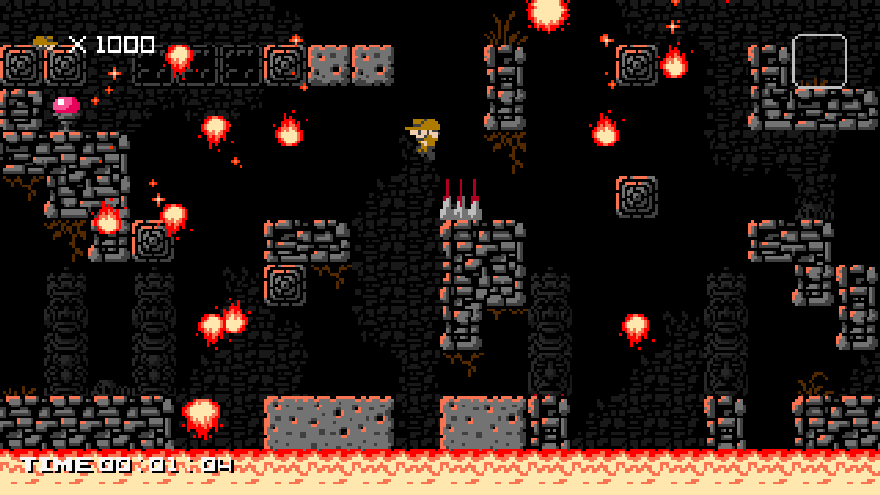

But Bill Murray never had to contest with deadly spikes, lava pits and sliding ice puzzles in Groundhog Day, if I recall correctly. And Aban Hawkins’ is not here to become a better person, learn how to play the piano, or get the girl. He is here to get the treasure. Deadly temples are his February 2nd, and to survive them, he needs to become a flawless, death-defying acrobat. He’ll fail, repeatedly, undoubtedly, but as Ernest Hemingway wrote, “A man can be destroyed, but not defeated.” When you finally witness him thwarting impending doom by the skin of his teeth, deftly leaping between crumbling rocks and blood-soaked spikes, answering flying daggers with more flying daggers, the satisfaction and relief that arise upon completion is intoxicating. Then, like a glutton, you come back for more.

Cycles of death and success are present in many video games, but in few do the lessons feel so deliberate. Every time the game informs you in capital letters that you have died, it is telling you that you missed the point. There is a very explicit path that needs following, and if you stray one step off of it, chances are you’re toast. This isn’t a game where you get to “play your way.” 1001 Spikes is a very particular cat, and there is only one way to skin it.

Learning your way through a level takes persistence, because in many cases, the only way to know what traps lie ahead is to witness them destroying you. Discovery becomes the most arduous, necessary, tense and exciting element of 1001 Spikes, because annihilation reveals precisely what not to do. Figuring out where death lies is only half of the equation, though. You also have to perform your calculations. The simple actions the game allows—jump, high jump, projectile and duck—must be executed with exact precision. Unresponsive controls kill games designed for difficulty, and 1001 Spikes makes sure there is no excuse for failure. Movement has heft and accuracy, and the levels are finely tuned to reflect this. You can jump just far enough, throw barely fast enough and duck in a nick of time to somehow make it out alive. You memorize layouts, study patterns, develop timing and attempt your technique, slowly earning progress by inches, not levels.

The “skip level” option can feel like the only way out. But don’t do it.

When nearly every step forward feels like progress, overcoming an entire stage becomes more than an accomplishment; it’s a celebration, a triumph of the human spirit. Perfection becomes addiction. The designers have squeezed danger into nearly every corner of the game, but you have to learn to trust your ability to overcome. At times you’ll turn hopeless, lose faith, and the “skip level” option taunting you from the pause menu can feel like the only way out. But don’t do it. You’re better than that. You can do this. And when you do, you will know true joy.

Belief is magic. When there’s no guarantee you’ll make it out of this thing alive, drunk-like self-assurance is the only ticket out. Looking back on my conquest, I see how heavily the odds were stacked against me. I finished some levels with a 100-plus death count, bringing my chance of survival to under one percent. But somehow I persevered. Forget the old college try; I require blind will.

When I was a boy, I loved to sled. My favorite spot was called suicide hill, a drastic incline that sent small children plummeting towards a frozen abyss at breakneck speeds. One winter, my spendthrift parents handed me down my father’s old work boots, rather than purchase new ones for my rapidly growing feet. Hideously worn-out and too large for me, the sole had been reduced to a smooth, flat rubber. Ascending suicide hill was hard enough, but getting up there without traction felt impossible. Trying to mount that steep, snow-ladened hill in those crappy boots was infuriating. I repeatedly slipped back down as squealing kids whizzed by, laughing. But I was determined. I’d hit the bottom, buck up, and find a way to get a little bit higher, angling the soles of my feet at sharp angles into the snow, discovering roots to grasp and intermittent respite from the incline. I finally made it up.

I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed a sled ride more in my life, because I’ve never had to work as hard for one. A task which once felt insurmountable had been met. That’s not a feeling I’ve had with games for a long time—not even in Dark Souls. But somehow, the small scale trials found in the levels of 1001 Spikes bring me back. Grabbing the key and making it inches from the stage door before dying carries a similar weight, and makes realizing the far-fetched goal all the sweeter.