Based in Fribourg, Switzerland, artist Alfatih’s work brushes against interaction, in all forms and senses of the word. Sometimes, he works within the world of a game engine: he’s collaborated with clothing designers Party Chat to ‘hack’ GTA with their collection; he’s filmed his own vlog diaries within the Los Santos environment. In other projects, he creates ‘ping-pong’ between the digital and the physical realms—elements like 3D-printed wearable prosthetics, screens rolled on wheels, or Alfatih-themed AR face filters. Though ever-expanding, the core of Alfatih’s body of work lies in the following question: How are identities formed and conditioned between the physical and the digital? “This back and forth [between the physical and digital] is what’s interesting to me,” the artist notes.

Alfatih made time to speak with us about the non-neutrality of the web (and of his homeland), what it means to be working on the fringes of games, fashion, and fine art, and the theory of ‘Strange Familiarity’ as it relates to the digital avatars he creates.

NON-NEUTRALITY

Can you start by talking about your childhood, your origins, and your upbringing? When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

It was a cliche childhood. I was constantly drawing on a board. I didn’t think much of it at the time. I was just drawing and creating things. I became curious about architecture, industrial design, and animation as a pre-teen. This was the time I started working more with CGI and 3D software. I started by creating speculative buildings or objects, and later got into making characters. I was also interested in this idea that 3D softwares offered a lot of freedom but incorporated constraints as well, in that it borrows characteristics from the physical world—you can apply physics rules or simulate materials and lighting. I then went to ‘visual communication’ school, which I thought was art school, but realized it was an advertising program once I started. It wasn’t that bad. a lot of what informs my practice today comes from there. Before diving into contemporary ads and campaigns, we were studying art history—not just as a set of references, but how images actually communicate and their effect on a given audience. Then I went to pursue a BA in interaction design, which is quite an open program. Some people come out of the BA and go into ‘startup mode,’ building apps or IoT. But you can also create installations and other free projects. This is where I met Jamie from Party Chat at the end of last year.

How has growing up in Switzerland shaped your worldview as an artist?

Where I live isn’t exactly the countryside. It’s more like a locality, but still five minutes away from farms and cows. There is a vending machine that pours fresh milk [laughs]. That kind of environment. I spent a lot of time on the internet as a kid.

Switzerland is a place where a lot of wealth is flowing. It makes you aware of your privilege. There’s also this narrative of Switzerland being a neutral country. In a similar way, I think of this myth about the digital space, where you can be and do whatever you want—but this is not true. Because you’re conditioned, and it’s not neutral. Each platform, each website, even the network itself—it’s so-called neutrality isn’t true.

At school, were you faced with the choice of attending the media interaction program versus a more traditional Fine Arts program?

I attended that program to have the actual knowledge of the tools and media theory. During the second year, there was a point where I had a clearer idea of the work I wanted to make, but it didn’t always fit the program. Whether it’s at school, at a job or any institution, you’re always conditioned within the rules and definitions given by that place. One needs to find ways of navigating and negotiating these boundaries. Sometimes, it’s better to quit and go somewhere else. I wasn’t going to leave six months before the end of the BA. My graduation project was rather informed by these experiences—so is the rest of my work.

Which video games did you play growing up?

I grew up as an avid gamer. I would say mostly, my first experience was playing on Nintendo 64 at some friend’s place, and Game Boy. The first console I owned was the first PlayStation. I was also interested in PC gaming; I didn’t have a type. Growing up, the game that marked me the most was Metal Gear Solid. Because it felt so different at the time, the way it was breaking the fourth wall and had a lot of narrative content. I got it when I was five years old, even though it was intended for a mature audience. I remember loving the cover at first sight in the gaming shop. I finished it many years later. Hideo Kojima was a fascinating figure growing up.

I’ve been playing less lately, but tried instead various games that focus more on gameplay or specific topics. I became interested during the last few years in games like Gone Home or The Stanley Parable, where the player is treated as a subject, with the emphasis put on the exploration of the space.

THE WORLD OF GRAND THEFT AUTO

What drew you to work within Grand Theft Auto as a medium or as an environment?

The internet was created with utopian ideals—with it came the idea that you can do or become whoever you want in it, which turned out to be less true over time. It’s still early for me to draw any conclusions of what has changed during the current pandemic in that regard, but I felt there was a greater shift in collective consciousness, where even more people realized that this utopia isn’t true. This GTA work was done before the pandemic and flirted with these ideas. I chose to work within GTA as it is an open world, exposing all the possibilities offered to the player and giving the illusion of agency. It takes place in a contemporary setting that mirrors the physical world. I considered the act of modding as a way of challenging the boundaries in a given game, and find alternative ways of navigating through it. With that, I explored performative behaviors that take place in digital spaces. It is interesting to explore the game as a social space and not just as a game anymore. As an example, when we used to play too much as kids, my mom could simply tell us, « Stop playing and go outside ». It was fine since we mostly played offline. But now, games are social spaces on their own in the mainstream. — My little brother is constantly connected with his friends when playing Fortnite. If I tell him to shut the game down, I’m in a way telling him to stop being with his friends, which can cut him off from his group.

You’re working within game engines and with code. What do you see are the significant differences between these two modes of construction?

I worked more with Unreal than Unity lately. Unity has an advantage when it comes to creating quick prototypes.

I like using code because of the way it connects to many different mediums. When you work with code, you can create interactive content, music, or visuals, and so it blurs the line between disciplines. Some artists define themselves as painters, sculptors, etc. I can use code and integrate it into an installation or a sculpture and not define my practice by a medium, but rather by some processes or intentions. I then use the right tool for it.

THE DIGITAL GARMENT

You also have work that provokes very kinetic or physical interaction with the viewer. How are you thinking about how wearing a garment might be an interaction?

We used to upcycle clothes with a group of friends, or play with random found objects that we used as garments. There are aspects of fashion that interest me, like the way it’s constantly evolving and tries to forget previous collections. There’s this perpetual question, What is fashion? that keeps coming up, as something that is constantly looking for itself and is always redefined.

Later, it collided with the work in GTA, which was generally more about the myth of becoming anyone in the digital space, but also how one’s identity is built and conditioned. Fashion in that context was used as a bearer of value and relating to one’s identity and status. I consider that a physical garment is already digital in a way because it already has a kind of digital value. When buying a luxury shoe for example, it has a certain value online with the ‘clout’ it brings you.

We spoke to the designer Gareth Wrighton who designed a video game within Unity, and showed his fashion collection in the game. He hand knit a sweater for hours so that he could render it in unity. His whole thing was the fashion scene or sphere is inherently virtual; he’s interested in the image of objects too. Does this resonate with you? What draws you to creating virtual garments?

That’s what’s interesting—not to consider only physical, only digital, but see how both interconnects and one influences the other. This back and forth actually is what’s interesting to me.

I was telling you previously that I was ‘trapped’ in advertising school—but it was very valuable to have studied branding, communication, semiotics, and how content flows. The circulation has evolved greatly—before, it did so in a unidirectional way via a limited number of media channels. Now on the web, users are both consumers and producers of content.

What’s the first step in your general creative process?

It varies. I keep doing research on the side, that can sometimes end up in a project, but not necessarily. I’m interested in how tools and technology evolve. I try to keep up and observe when a new algorithm appears, what it does, and what are its effects in a given social or political context. When working on projects—usually ideas can come through prior experimentation, or can be more conceptual… it then takes the form that it needs to take.

Is collaboration a big part of your process?

I like collaborating with people with complementary skills and knowledge—musicians or sound designers, for example. Most of the time, collaborations don’t happen as collaborations per se, but can simply start from discussions and exchanges I have with people. Sometimes, ideas can stem from everyday situations, like a photo taken during vacation, or an object given by a friend. I try to stay open for new inputs from my surroundings—keeping it organic.

BETWEEN THE PHYSICAL AND THE DIGITAL

BASE Services contains both a physical and a digital component as layers in space—physical screens are utilized as ‘windows’ to ‘scan’ tangible garments. How did the project BASE Services come to be?

There were certain expectations that needed to be met at the end of my design program. Working with fashion enabled me to be more fluid—it can work in both an art and a design context.

BASE Services was presented as a fictional fashion service that operates between physical and digital spaces. Garments were presented through different forms. Second-hand clothes were placed on stands. Clothing mods were available to be used in games. And there was a screen on wheels pushed by performers—a window to valorize the thrifted clothes. So [the project] is always about negotiating all these subjects that we’ve been speaking about—the ping-pong that happens between spaces.

I wanted to break down some of the ideas of that project, and that led me to first start working with shoes. They’re these very cheap slippers with a 3D printed prosthetic on top. Again, it’s this idea of colliding this digital prosthetic that becomes physical through 3D printing, which maybe gives it a different dimension to the already existing shoe. You don’t need to understand the whole process behind it, even though it’s a process-driven work. It can also be appreciated on its own as a sculpture. Works can have different layers in the process through which they’re created, but I also like it when you can appreciate them at first sight. I don’t have a recipe for that, but it’s something I always keep in mind how accessible a work should be.

Can you expand how you are thinking of these prosthetics in terms of utility? Do you view the act of wearing a garment or performance as a form of interaction?

I was playing with the language of utility by presenting them as products. There’s a website where you could download the prosthetics. I was extracting parts of luxury shoes, like the Tabi boots by [Maison] Margiela or the Jugo boots by Comme des Garçons. Basically, applying a fragment of luxury on existing footwear, like a partial bootleg. Once this language was put in place, I opened up the designs a bit. I took some other shapes like the scorpion. At the show’s opening, instead of being installed, I invited performers to wear them. They were just walking around and out of the gallery. They weren’t ‘performing’, per se, or doing anything crazy. Their performance was them just hanging around and having this shoe on their foot. But with all that, the shoes weren’t very usable. We needed to have straps to attach them properly. So there’s also this humorous contradictory dimension of not really being shoes you can wear, but sculptures in the end.

Can you talk about On Vacation and what it meant to recreate a personal archive, little memories from your phone, through GTA?

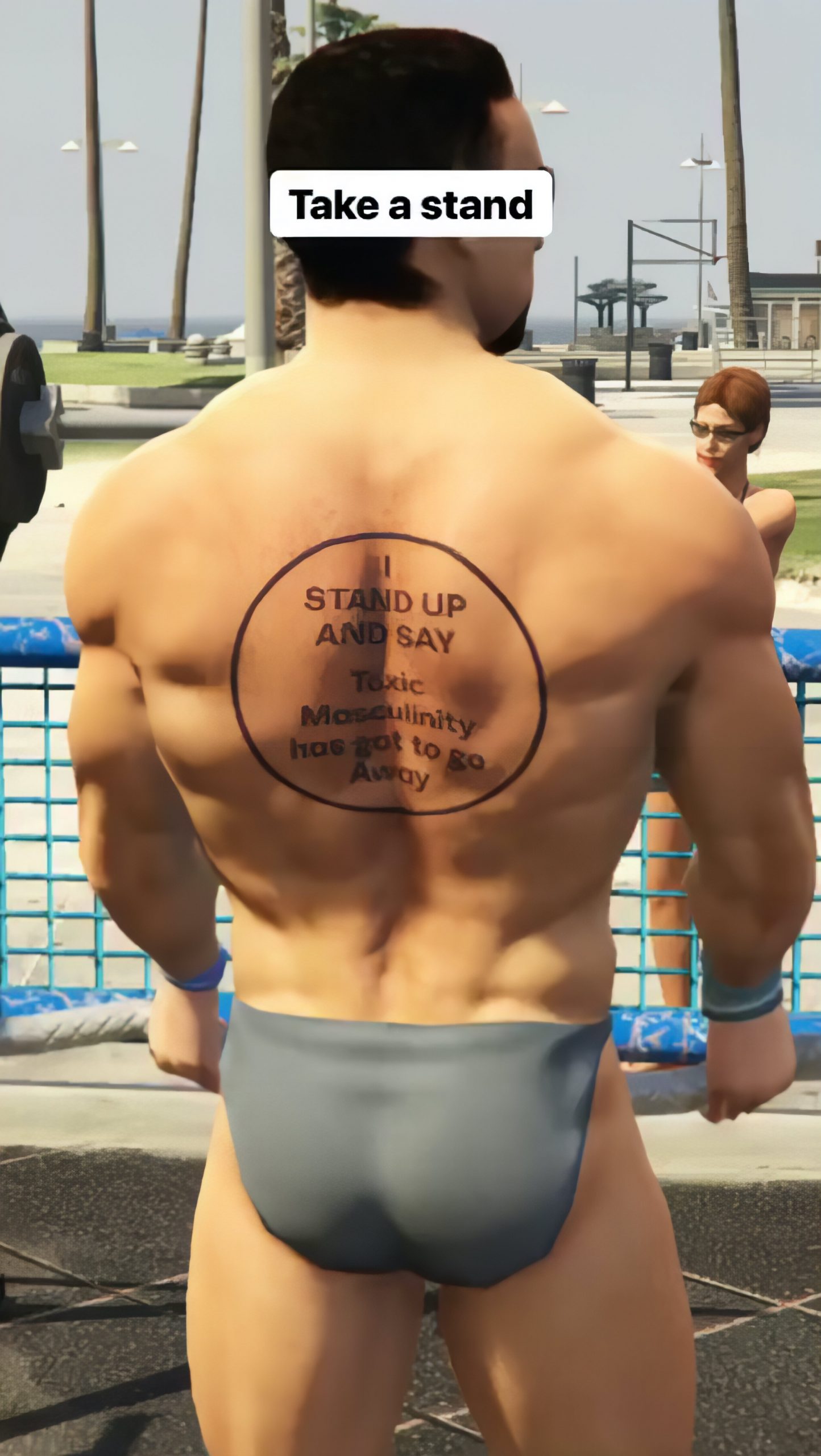

That was the first project where I modded GTA. I modelled myself and integrated in the game. I was recording within GTA and then uploading to Instagram actually every few days for a total of five weeks. For those weeks, my only Instagram stories were ‘digital’ adventures within Los Santos. I had plane shots, then arriving in the city, and existing within it. So the project was about GTA as a platform, but it was also about Instagram as a platform. There was a mix of things that were staged in the environment, and some elements captured from just walking through the game and capturing things ‘as they are’. And maybe, my avatar’s reactions to them. I was also reenacting performative gestures that are done in the digital space. Things like selfies, giveaways, e-begging, performative activism, footage of protests, those kinds of videos that are quite common on Instagram stories today.

I would also take into consideration people’s reactions in terms of how the continuity of the story was built up. It was interesting to make some observations about many subjects because people were confronted with the videos. Some people even thought my videos were of events that really happened! For me, it’s easy to recognize, Okay. These are screencaps from a game. Even one month ago, someone asked me, “Oh, so you really tattooed someone on the back?” It’s reactions like these that also inform how, on the smartphone, things can seem more real since they’re less detailed and seen through a small screen.

Of course, we’re not all trained visually in the same way. If you’re used to playing games, it’s easy to recognize this footage as CGI. If not, then maybe some shots can feel more photorealistic than others—the same way all the games from the past looked so ‘realistic’ or advanced at the time. That wasn’t planned or part of the project at all.

STRANGE(R) FAMILIARITY

Perhaps it’s making a comment on labor as well. Everything thinks Instagram stories of as fleeting moments you film on your phone. The fact that you’re putting in all the effort to create and film a world and then go through the trouble to make it the right dimensions to upload onto Instagram really reveals how narrowly people view the ways social media can be used.

This is an important point. Instagram Stories are ephemeral and used to be limited to content made in the past twenty-four hours. This unconsciously implied that they were ‘authentic’, made ‘in the moment’ and were not staged. But no—it’s all staged. I was staging it even more by making these gestures behind my computer screen, from a computer game. I think a lot about these digital avatars that appeared in the last few years like Lil Miquela and so on. And it’s interesting to see how people react to them and think, Oh, no, this is fake. Hatsune Miku was an earlier example too and maybe Gorillaz to a certain extent. I don’t know if they realize that everything is constructed anyway whether it’s CGI or physical. There are nuances, of course, but in the grand scheme of things, however, it’s content that is produced. You’re operating within platforms that condition you in the ways you interact with and present yourself. It’s maybe a generational shift that will slowly happen. Younger people are already less into this constant ‘self-branding’ dynamic.

Thinking about the identity of the avatar and self-branding—could you speak about the AR filters that you create and Decentralised Identity? What does it mean for you to have your friends and strangers appear as yourself in digital form?

Projects like these don’t take themselves seriously but are still done in a serious way. This began as a joke among friends—I’ve had the same look every day for the past four years now with my hat, my glasses, and my braids. It became associated with me. Before Instagram filters existed, I made some related projects, coding the look by myself. I was interested in how things become icons through repetition.

Eventually, it was launched as a filter. When you put something online, it sometimes takes an unexpected path. What was interesting was when complete strangers were using it because they have no idea about what it is or where it comes from, but they’re still using it so casually. This was the funniest reaction—of my friends sending me the Instagram stories of strangers from around the world ‘dressed’ like me.

I was reading a paper by Theresa Senft on this idea of ‘Strange Familiarity.’ She writes about how in the physical space, there is a specific term [‘Familiar Strangers’ by Stanley Milgram] for people that you know—maybe from your commute to work, or maybe you see them at art openings. You might see the same people all the time, but you’ve never actually spoken to them. They’re still familiar faces, and the existence of these is registered for you. You both acknowledge each other’s existence, even though you don’t really know each other.

In the digital space, something similar happens. On Instagram or Twitter for example, there are people that are not so far physically from you—you don’t know them, but you acknowledge their existence through the screen. When you meet physically for the first time, something happens because you think if you have a pre-existing knowledge of who they are. So this extends to digital space; this happened with the filter I made. People were using it, not even knowing that it was related to me, and the first time they met me physically, they said, Oh, you look like that filter on Instagram.

What are you currently working on?

I’m usually working under pressure with multiple projects at once, but trying to slow down now and take more time for personal work. I’m planning a residency next year. I also want to take time to question not just [the] subjects [I work with], but also my own way of working, my own way of conceptualizing things. I want to come back to making interactive physical objects.

Credits

Condensed and edited for clarity.

Interview conducted by Alex Westfall in October, 2020.