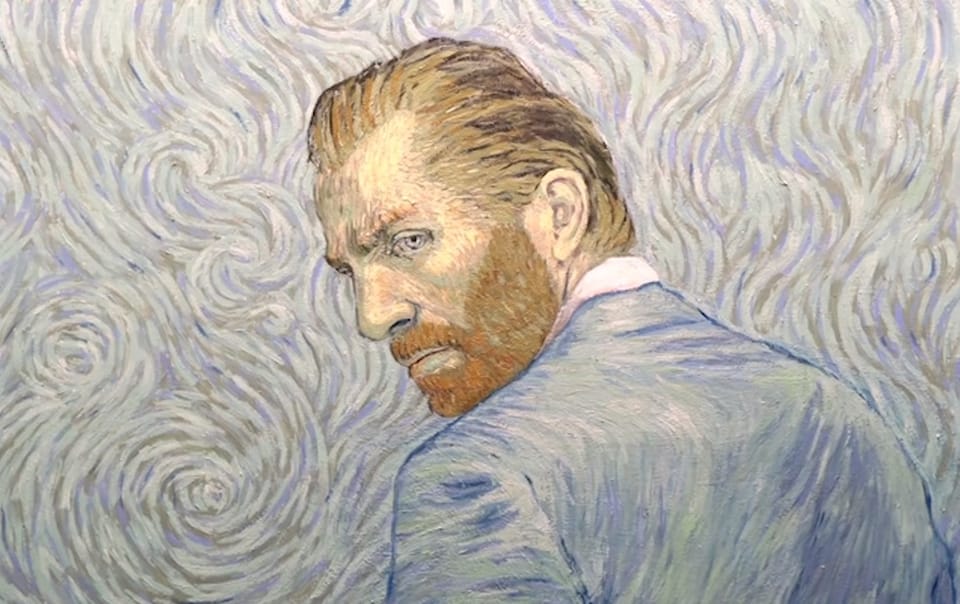

Animated Van Gogh film is made entirely with paintings

Vincent van Gogh occupies a special place in the Western psyche. His legacy mythologized the idea of the tragic artist who nevertheless makes beautiful art. The Starry Night (1889) is so iconic the painting was used to symbolize Cory and Topanga’s fraught relationship at the height of Boy Meets World’s popularity. It’s not surprising, then, that Van Gogh’s life is the subject of a new animated biopic called Loving Vincent.

When Variety reviewed 1956’s Lust for Life, based on a novel by Irving Stone and starring Kurt Douglass as van Gogh, it called the film “a slow-moving picture whose only action is in the dialog itself.” The screen adaptation was considered faithful but flat, and colorless by many, seemingly the opposite of van Gogh’s dazzling work and conflicted life.

the film uses thousands of paintings in the style of Van Gogh

Loving Vincent takes an altogether different approach. Directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman commissioned an army of over 100 painters to tell the story of van Gogh’s life based on hundreds of his personal letters. Running at 12 frames per second, the film uses thousands of paintings in the style of Van Gogh to create a space around the artist’s life and monumental works that can be explored visually.

It’s an unusual approach that seems well suited to the unique flow and texture of Van Gogh’s paintings. While Bedroom in Arles (1888) might make for the perfect movie set, it fails to capture the dynamic brush strokes and movement of something like Road with Cypress and Star (1890). The same eccentric style and kinetic interplay of colors that make Van Gogh’s work so beloved and accessible are also what make it so uniquely untranslatable into other media. Rather than re-imagine his work, Loving Vincent serves instead to extend it.

The art critic Arthur Danto considered Van Gogh, along with Paul Gauguin, to be one of the first truly modern painters. In After the End of Art (1997), Danto wrote that modernism was “marked by an ascent to a new level of consciousness.” Instead of focusing purely on representing their subjects, Van Gogh and those who proceeded him were more concerned with the “means and methods of representation.”

Loving Vincent gives this theory a sort of visual clarity by helping to bring Van Gogh’s idiosyncratic style to the forefront. What slowly becomes clear while flipping through a book of prints takes on a new immediacy when the artist’s work is fleshed out into a continuous whole: the thick, gloppiness of the paint, the swirling nature of its contours, the menacing instability of the compositions.

In Van Gogh’s work, ego supersedes the subject by relying on a level of conspicuous artifice that would have offended painters from generations prior. No doubt it’s a significant part of the appeal. Café Terrace at Night (1888) just wouldn’t be the same if the bright yellows and deep blues of its city life weren’t juxtaposed with our knowledge that the man who painted them also chopped his ear off and later killed himself.

Loving Vincent is currently being shepherded to completion by Breakthru Films, the studio founded by Welchman, previously a producer on the Oscar winning animation short Peter and the Wolf (2006). You can find ongoing updates on the project at its Kickstarter page.