Aragami is a shadow of what it could be

In 1995, the Guinness World Records Committee officially decreed that a parakeet named Puck had the largest vocabulary of any bird in the world. Puck knew 1,728 words, and like others of his species, was able to assemble them into phrases and sentences appropriate to the situation he was in. “It’s Christmas,” he was heard to say on the proper day in 1993: “That’s what’s happening; that’s what it’s all about.” Puck might have been exceptionally literate, but he was only one voice in a diverse avian chorus. Amazon and African Grey parrots are known for their conversational skills, as are corvids, magpies, and mockingbirds. Starlings are often mistaken for real people. And Mynahs are perhaps the greatest mimics of them all—provided that we don’t include that rarest of breeds, the Matthew McConaughey fan.

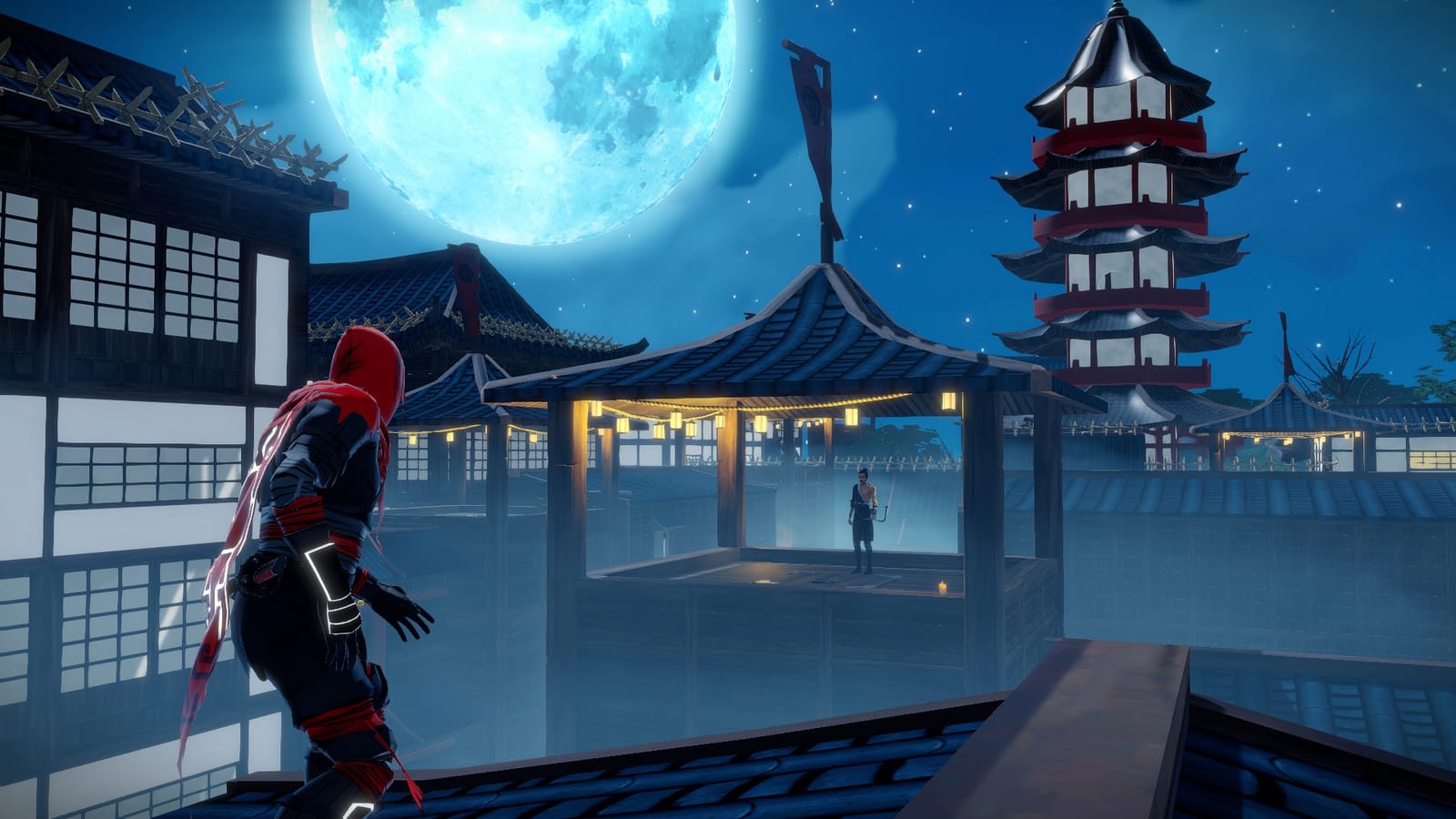

There is a bird in Aragami whose introduction promises great things. This raven, Kurosu, is locked up in a pagoda that is as heavily and incompetently guarded as every other pagoda in the game’s mythical version of ancient Japan. Yamiko, your guide and telepathic companion, tells you that this captivity was arranged so Kurosu doesn’t fall into the wrong hands. Kurosu is, admittedly, a stylish fellow, with a purplish tinge to his down and one wing tipped with crimson. But compared to Puck, he’s a dunce: no speech, no songs, no existential musings on the Christmas spirit.

the game oversells its weakest ideas at the cost of the strongest

The raven’s ostensible role is to help you navigate your way through the game’s 13 missions, most of which require you to sneak through groups of enemies by disabling proto-digital “light barriers” which block your way. Occasionally, Kurosu will screech at one of these barriers to give you its location. But usually his telepathically relayed directions are maddeningly vague: “Reach the next area,” or “Find an exit,” or “Infiltrate the pagoda.” You wonder: is a pagoda really something to be “infiltrated?” And where is that exit, anyway? But Kurosu only caws, and leaves you to figure it out on your own.

Kurosu the raven is symptomatic of a persistent problem in Aragami: the game oversells its weakest ideas at the cost of the strongest. At its core, Aragami is a very straightforward third-person stealth adventure. You’re a ninja; you sneak around in the shadows; not infrequently, you assassinate people. Everything else should be window dressing. But while the game makes a lot of noise about the magical bird and (admittedly cool) shadow dragons that you can summon to consume your enemies, the core stealth experience feels frustratingly underdeveloped.

The quality of a stealth game is invariably defined by the responsiveness of its enemies, and your foes in Aragami—the Kaiho army, which uses mystical light weapons against your shadowy assassin—barely qualify as sentient. They’re always surprised to see you, even in the missions where they are supposed to be looking for you, and yet they’ll forget about you after a few seconds if you jump back in the shadows. You can stab one in the back, and it will barely register with his friend standing five feet away; you can run across a room in the center of someone’s sightline, and you’ll have diced them before they can even manage to draw their sword. When you’re in a building with enough walls, you can drop the pretense of stealth altogether and just run from room to room stabbing your hapless enemies; the game promises you 100 points for every one of these “stealth kills.”

Aragami’s central addition to the genre is that it lets you manipulate shadows instead of just hiding in them. Your character is able to teleport from one shadow to the next, and create new ones by using your expendable “shadow essence.” In addition to being a neat thematic twist—what are stealth games about if not sneaking around in the dark?—it is a creative way to represent a ninja’s characteristic lightness of movement. But the execution of this idea is nothing but frustrating: the jump range is small to begin with, and often it simply doesn’t work when it should, leaving you stranded. If you create shadows, the game inexplicably makes you wait and watch until the shadow shrinks to a certain size before it will let you jump. This makes graceful movement across open stretches impossible, and forces you to crawl along the edge of every map so you can afford to wait for your abilities to work properly.

the game inexplicably makes you wait and watch

These kinds of imprecise mechanics might matter less if Aragami was more like, say, The Last of Us (2013), which incorporated stealth tactics as one of many approaches to telling its story. Perhaps it is unfair to compare Aragami to one of the great games of the decade, but it is no compliment to any piece of art to say it is merely good for what it is. And Aragami does give signs of wanting to exceed its own self-imposed boundaries. The game allows you to wield a small variety of weapons as you go on, for example, including projectiles and the aforementioned dragons—but since one hit from any enemy kills you, you are forced to wield these devices from the cover of darkness. Even when you’ve obtained the available supplements, open battle remains impossible. The game thus retains its stealth focus, which means that the tiny hiccups in core movement patterns obstruct the very continuity of the experience.

The Last of Us took a boring idea and made everything about it sublime; Aragami takes a lot of good ideas and neglects to make any of them great. Even the story feels uninterested in itself: the cutscenes are mostly under 10 seconds, and the characters habitually preface expository statements with phrases like “By the way” and “In case you were wondering.” When you reach a destination, your guide Yamiko has a way of exclaiming “Finally!” as if she couldn’t wait for the mission to be over. But a good game, like any good work of art, should make you wonder; it should give you a reason to care about what happens, just as it should give you reasons to enjoy what it asks you do. Aragami feels only half-invested in doing both of those things, so it does neither. By failing to follow through on its own best ideas, it leaves us with nothing but a shadow of the game that could have been.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.