As you walk into Gallery 625 of the European Paintings department in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you confront a rather puzzling work. Madonna and Child, by Italian painter Duccio di Buoninsegna, is much smaller than its neighbours, barely the size of a standard US letter. While its peers float in ethereal realms of shining gold, Duccio’s gilding lacks lustre, the tracery of cracks on its surface evincing the painting’s extreme age. Even the colors are not as bright. Mary’s dress, which dominates much of the scene, appears to be painted in somber azurite, rather than the brilliant ultramarine that joyously adorns her virgin frame throughout most of the museum. It is certainly a beautiful piece, just not as arresting as many of the Met’s masterworks. Why then, does it warrant a private glass case, placed in the most prominent and accessible part of the gallery? Why did the Met, according the New York Times, spend $45 million, the highest value it has ever paid for a single piece of art, on a seemingly unremarkable depiction of the Madonna?

Before Duccio, depictions of children in Western art were always symbolic of the divine

The answer lies not in how Duccio’s famous work looks, but what it represents. Take a look at how the infant Jesus and Mary interact and gaze at each other. Before Duccio, depictions of children in Western art were always symbolic of the divine. A stern baby Jesus with adult features (such as a full beard) would regard the viewers with an imperious air, sitting on a Mary whose sole purpose was often literally that of a seat, a sedes sapientiae or “Throne of Wisdom”. To Susan Douglas at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, this particular painting is a departure from the norm because it “expresses the emotions of love and tenderness between mother and child.” This is arguably the first time in Western art that a child is allowed to simply be, and not just act as a stand in for some moral or spiritual higher purpose. Duccio paved the way for other artists, writers, and thinkers to become much more interested in depicting children.

Which brings us to today, where adults regularly consume media originally meant for a younger audience, especially the young adult audience. Be they books, movies, or games, adults are unabashed about their interest—and often obsession—with YA (Young Adult) media. To explore where the appeal lies, let’s first take a look at what children’s media actually is.

Children in Art

While Duccio’s legacy allowed artistic luminaries to depict children, understanding them was another matter. Indeed, the depiction of children in western art has rarely given much agency to children themselves. In Pictures of Innocence: the History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood (1998), art historian Anne Higonnet claims that until the mid-18th century children were considered “faulty small adults, in need of correction and discipline.” At that moment in time, society shifted and, instead, as the University of Virginia’s online project ”Age of Lost Innocence” describes, “Society adopted the idea of the ‘blank slate’ and beginning life in a state of unconsciousness. Art reflected the transition: no longer vessels of psychological and sexual awareness, children became asexual, physically neutral, and psychologically unaware.”

Duccio’s Madonna and Child via the Met

Complicating matters, of course, is the fundamental question of “who is a child?” Scholar of children’s literature Mavis Reimer, in her article “Readers: Characterized, Implied, Actual,” questions our very notion of a child. “Both child and the term in opposition to which it is defined, adult,” she writes, “are understood to index positions within a system rather than to have intrinsic content in and of themselves.” Our concept of the 18-year-old as an adult is fairly arbitrary, recent, and far from universal. Biologically, a 13-year-old that can reproduce is considered an adult.

The history of what is considered “childhood” and how to depict it is complex. Regardless, as Roy Lowe contends in his 2004 article “Childhood Through the Ages,” it was only at the turn of the 19th century and the advent of universal education in Britain, that mainstream Western artistic content transitioned to being “about children, and for them.”

the fundamental question of “Who is a child?”

Where we once had little material to entice those considered too “immature,” we have a whole industry. In the last few years especially, the market for children’s media has exploded. In 2015, Publishers Weekly stated that “children’s print book sales around the world in the last couple of years have been nothing short of fantastic” and that “total print sales in the US rose 2%, but children’s was the key driver, with 13% growth.”

Notwithstanding the fuzzy definition of “childhood,” it’s undeniable that young humans do have different tastes than adults. If common sense weren’t enough, let a 1993 study by Barbara Lehman and Patricia Scharer convince you. In their experiments and subsequent paper titled “Children and Adults Reading Children’s Literature: A Comparison of Responses,” the two researchers conclude that, while “children are capable of analytical, interpretive and evaluative thinking,” “children tended to take the book more at ‘face value’” as compared to adults, and “child readers made few comments about themes”.

But, of course, it’s precisely those fuzzy boundaries—those contested realms under whose twilit skies “juvenile” and “adult” media froth and swirl in an endless maelstrom—that invite exploration.

Young Adult Literature

The world of “Young Adult” content is one such area that sits in the middle. While the term tends to mean teenagers aged 13-17, Young Adult content tends to have a far bigger reach. It’s not even surprising any more to hear that Young Adult media is consumed more by adults than by teenagers themselves. Jim Milliot at Publishers Weekly reported (along with the cold, hard numbers) that between December 2012 and November 2013, “The single largest demographic group buying young adult titles in the period was the 18- to 29-year-old age bracket” (and it might also be worth noting, in case the word “adult” was thrown around lightly, that the average age of marriage in the US is around 28).

This trend hasn’t gone on without drawing some ire. In 2014, Ruth Graham at Slate lamented the falling literary standards of grownups. “We are better than this,” she bellowed in loud pull quotes, maintaining that “adults should feel embarrassed about reading literature written for children”—the emphasis is hers. The backlash was swift and widespread, with authors, critics, and librarians coming to the defence of indignant YA fans, condemning Graham’s arguments as simplistic and short-sighted. Indeed, literary agent Sarah Burnes argues in The Paris Review’s blog that “the binary between children’s and adult fiction is a false one, based on a limited conception of the self.”

the binary between children’s and adult fiction is a false one

If Burnes’s statement seems at odds with the previously mentioned study by Lehman and Scharer, it’s worth perusing professor of Library Science Amy Pattee’s cogent article “Is it Time to Move the Books: Considering Your Library’s YA Fiction Collection,” where she proposes that “we might begin to think about young adult literature as a genre rather than an audience designation… like horror, romance, fantasy and science fiction that teens and adults enjoy reading.” To Pattee, YA literature is not lesser, merely different, and possessing tropes and common themes just like any other genre. “Young adult books, then,” she continues, “are distinguished by their attempts to capture an authentic teen voice that may, by virtue of the teen character’s lack of a teen character’s lack of time spent on earth…be ‘linguistically narrow’.”

Steven Universe, Transformation, and Fantasy

Underscoring Pattee’s thesis are media that unabashedly cater to a dual audience: children as well as their adult guardians. Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe (2013-present) is one such example. As Emily Gaudette writes for Inverse, “Steven Universe…is not quite a children’s show that appeals to adults as a secondary demographic; it satisfies both groups.”

Steven Universe is an animated TV show about a preteen boy, the titular Steven, and his three monster-fighting, alien aunts, The Crystal Gems. Created by Rebecca Sugar, Cartoon Network’s first solo female show creator, the show has garnered numerous awards and much critical praise.

The show certainly has a lot going for it. Its pastel interpretation of a (semi-) post-apocalyptic Earth dominated by pinks, purples, and aquamarines is gorgeous. Its original music, much of it composed by Sugar herself, is sublime, ranging from charming folksy numbers about Steven wanting to see his aunts’ superpowers, to hip-hop anthems about the power of mutual love.

But it’s the writing that really speaks to adults. The world of Steven Universe is a rich stew of fantasy and science-fiction, its sweet overtones masking surprisingly bitter notes of longing and sadness that waft out when you least expect it. But as any good piece of speculative fiction, the fantasy elements are a metaphor for something much more real and relatable. In this case, that something is the idea of growing up and transforming.

Much of YA fantasy deals with transformation. As YA novelist and English professor Marie Rutkoski puts it for i09, “Transformation is fantasy’s bread and butter. Magic, new creatures, new worlds—all either show transformation in its very act or transform a perception of reality. Fantasy is deeply invested in the liminal.” Steven longs to grow up and transform into a fully-fledged Crystal Gem. He’s often troubled by how his alien mother, in order to birth him, sacrificed herself and essentially transformed her essence (her gem) into the boy named Steven. His brief foray into seeing the future in the episode “Future Vision”, to quote Wired’s Eric Thurm, “makes literal the terrifying, exhilarating epiphany of childhood growth.” And he’s fascinated by how his aunts can fuse into one powerful being and even sings about it in the episode “Giant Woman,“ which Kendra Beltran of Cartoon Brew surmises is a “a symbol for a growing boy going through some changes.”

Fantasy is deeply invested in the liminal

Most notable is the episode “Alone Together,” where Steven himself gets to fuse with his crush and best friend Connie Maheswaran, and experience a real transformation. The two’s combined and transfigured self, the older, gender-ambiguous Stevonnie, serves both as a vehicle to experience the anxieties and exultations of adulthood, and as a gentle metaphor for burgeoning sexuality, a literal “coming together as one.” Sugar herself has commented on Stevonnie as “a metaphor for all the terrifying firsts in a first relationship, and what it feels like to hit puberty and suddenly find yourself with the body of an adult, how quickly that happens, how it feels to have a new power over people, or to suddenly find yourself objectified, all for seemingly no reason since you’re still just you.”

Rutkoski argues that it’s the idea of transformation in YA media that draws in so many enthusiasts of all ages. “Readers—of any kind of book—want to behold a transformation,” she writes. “First experiences draw us in because they are the crucible for change. And while of course we expect adult characters to cope with change… it is not patently the essence of the adult experience in the same way it is of youth.” Rutkoski’s final statement is probably the most significant: that change is the essence of the young adult experience, and therefore YA fiction is the best medium to depict it. In On Three Ways of Writing for Children (1946), preeminent author C.S. Lewis notes that sometimes, one writes a children’s story purely “because a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say.” Through Steven’s naïve eyes, the complications of life are simplified and flattened, the rose-tinted shadows a very literal depiction of his worldview. As such, acts of transformation are felt more strongly by the viewer, who shares in his gaze and naiveté.

“The medium is the message,” Marshall Macluhan’s famous quote from his 1964 book Understanding Media: the Extension of Man, is often cited by game designers as a guiding principle of good design. Steven Universe shows that the principle holds true for any medium, and that for certain themes, children’s literature and programming really is the most potent medium for conveying the message.

Oxenfree, Escapism, and Nostalgia

Once Macluhan has been invoked, it’s inevitable to fall down the rabbit hole: can we exploit an even better medium to convey our message? Certainly: videogames. Growing up and transforming aren’t mere abstract entities, they are processes that one undergoes. And as influential games scholar Ian Bogost makes the case for almost ad nauseum in his book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (2007), gameplay is exceptionally well-suited to convey messages about procedural concepts. “When we recognise gameplay,” he says, “we typically recognise the similarities between the constitutive procedural representations that produce the on-screen effects and controllable dynamics we experience as player.”

Which may explain why the gaming industry seems to have been taking a keener interest in YA narratives, with well-received teenage-centric titles such as Life Is Strange (2015) and this year’s Oxenfree. It’s good to note that some of these titles might not actually be targeted at teens, which would make for a further blurring of the arbitrary divisions between “Adult” and “Young Adult”, and yet another point in favor of Amy Pattee’s “YA-as-a-genre” idea. Life is Strange, for example, whose plot follows a (albeit super-powered) teenage girl, was deemed “Mature” by the ESRB (which is one step above “Teen”).

Oxenfree is an interesting example because it performs little of the “escapist” work that is so often attributed to YA media, and to its appeal in the adult market. In an article in The Guardian titled “Why are so many adults reading YA teen fiction?” Goergina Howlett writes that “the fantastical worlds and sheer inventiveness and imagination of YA is rarely rivalled by adult literature.” This stance is debatable. Writers such as Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, and China Mieville have painted us highly detailed pictures of fantasy worlds geared originally to an adult audience (their diverse readership, notwithstanding). The argument that credits the popularity of YA literature merely to escapism robs the literature in question of much of its complexity.

Unless your escapist fantasy is to return to your adolescent youth, Oxenfree’s core tenet, one could argue, is precisely the opposite of fantasy escapism. Rather, the game focuses on the real, on nostalgia, and returning to what it felt like to be a teenager. While the horror elements of the game are certainly important, they aren’t the heart or even the best-executed parts of the game. “Oxenfree is absolutely a game about teenage bullshit,” Chase Ramsey wrote in his Kill Screen review, while to ZAM’s Nate Ewert-Crocker, “Oxenfree feels very authentically a game about being an adolescent, as though someone had scrubbed all the awkward teen-isms from Life is Strange and replaced them with more realistic dialogue.”

Oxenfree’s core tenet is precisely the opposite of fantasy escapism

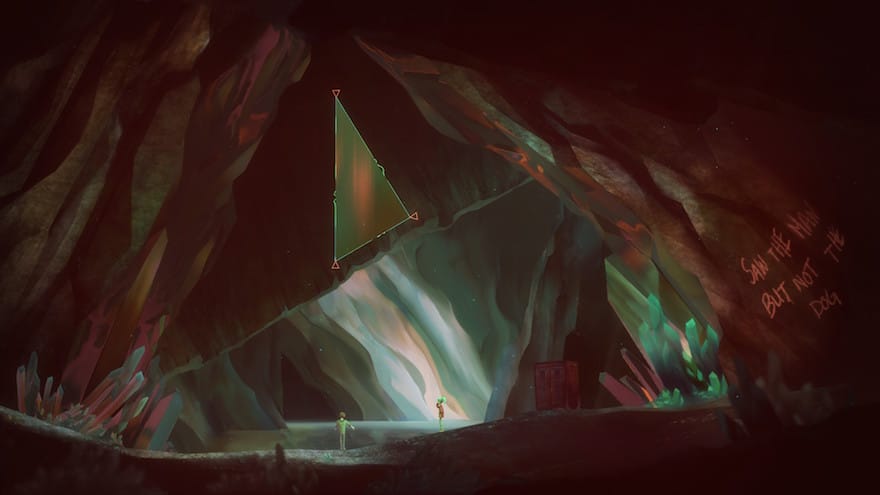

That’s not to say that escapism is bad, or that Oxenfree eschews all forms of escapism completely. On the contrary, the game begins with your protagonist Alex, along with her new stepbrother and her best friend, reifying the idea of escape as they head to a lonely island to indulge in what they hope to be Dionysian revelries with fellow classmates, complete with drugs, booze, and sexual tension. And it’s easy to get drawn into the striking art. Where Steven Universe engages you with soft, warm tones and quirky charm, Oxenfree intrigues you with haunting but wonderfully detailed backdrops and moody lighting, lighting that casts more shadows than it dispels, birthing patches of darkness pregnant with sinister possibilities.

While the narrative progression and the puzzle-solving in Oxenfree is fairly linear (and in the case of the puzzle mechanics, somewhat tedious), it’s your interactions with the well-rounded characters that constitute the emotional core of the story. It would have been fairly easy for Night School Studio to inject high-school stereotypes and teen angst into the game’s story, but they display admirable restraint, focusing on believable dialogue and tense shifts in relationship dynamics. Much of the game involves you choosing what to say next, and while it doesn’t always alter the plot drastically, it does affect your emotional experience of it. Will your Alex be stubborn, silly, selfish, or sullen? Or even silent? It’s entirely up to you.

And yet, much like in the Mass Effect and Dragon Age games, the dialogue options you choose aren’t exactly what Alex says. No, she expands and elaborates, sometimes not entirely in ways you intended. To Ewert-Crocker, “the dissonance between prompt and response actually works to the game’s advantage.” It forces you to think of Alex as a separate character, not completely under your control.

Which makes sense for adult players. You aren’t a teenager, and playing as one won’t change that. But that’s not the point. YA media isn’t meant to be a fountain of youth, but a way for adults to rethink what it means to be a teenager, how teenagers view the world, and what grownups can learn from that. As Meg Wolitzer at the New York Times reflects in “Look Homeward, Reader: A Not-So-Young Audience for Young Adult Books”, with YA media, “I’ve been given access to a pure form of the complications involved with being young, now filtered through the compassion, perceptions (and barnacles) of my older self… it’s broadening to spend time around the losses and transformations of young characters without having to cast myself in the role of a parent or authority figure.” The gaze of a fictional teenager is alien enough to challenge adults and force them into confronting new perspectives, yet accessible, universal, and intensely familiar.

Monsterhearts, Exaggeration, and Emotion

On the opposite end of the spectrum from grounded portrayals of teenage interactions lies Joe McDaldno’s 2012 tabletop role-playing game Monsterhearts. In Monsterhearts, players take on the role of teenage monsters (such as vampires, ghosts, werewolves, and ghouls) in a modern-day setting. Like in any tabletop RPG, and unlike in most digital games, Monsterhearts players actually inhabit their characters, trying to determine precisely how their characters would think, act, and react to certain situations, even sometimes speaking in their characters’ voices. This doesn’t mean that they lose their sense of reality and become these characters (despite what the moral police of the 80s say): as scholars Dennis Waskul and Matt Lust argue in their paper “Role-Playing and Playing Roles: The Person, Player, and Persona in Fantasy Role-Playing,” a key part of playing any RPG involves separating and negotiating boundaries between the player and the character they’re playing.

But as discussed, playing a character can be a powerful tool to understanding different points of view, and a tabletop role-playing game intensifies this by allowing players to actually get inside a character’s head. Not that these characters are necessarily realistic. In her New York Times article, Meg Wolitzer clarifies that “The point of these books [or other media, in our case] isn’t just (or even necessarily ever) ‘verisimilitude.’ (If verisimilitude were the aim, then why not only read Y.A. novels written by 13-year-olds?)” In fact, Monsterhearts revels in exaggeration. In its world, teenagers are dark and mysterious, seductive and cruel, wielding both sex and violence as mere tools.

You play to get lost, and to remember

But the exaggeration is used for a purpose. As sociologist Gary Allen Fine wrote in Shared Fantasy: Role Playing Games as Social Worlds (1983), “by simplifying and exaggerating, games tell us about what is real.” Yes, Monsterhearts is about the supernatural, but it’s more fundamentally about the complexities of human emotion and action. The game’s introduction highlights this point: “You play because the characters are sexy and broken. You play because teen sexuality is awkward and magnetic, which means it makes for brilliant stories. You play because despite themselves, despite the world they live in, despite their fangs and their bartered souls and their boiling cauldrons, these aren’t just monsters. They’re burgeoning adults, trying to meet their needs. They’re who we used to be—who we still are sometimes. You play to get lost, and to remember.” So while a player might spend one scene negotiating a price with a demon (which could act as a metaphor for addiction, perhaps), they may spend the next agonizing over a prom date.

Monsterhearts allows adults to explore difficult emotions, emotions which they may have encountered in the past but still give them pause. In an interview with the blog Giant Fire-Breathing Robot, MacDaldno himself illuminates this further: “[As adults] we hit a point in our lives when we stop giving ourselves permission to be irrational, volatile, to live life in the moment. But those impulses don’t just vanish because we want them to.” And to truly understand this and the power of the RPG, it’s important to remember that a tabletop role-playing game is a collaborative experience. No single authorial voice controls the actions and the players themselves (helped by the game master) decide where the narrative takes. RPGs, and Monsterhearts especially so, hand players authority to decide what emotions to delve, what impulses to give into, and what temptations to fight. And if young adult stories are most conducive to such exploration, then so be it.

///

It’s nice to think of Duccio as a rebel. He defied liturgical convention to depict the actual human relationship between a mother and child. True, his piece was destined for a private home or chapel, far from the prying eyes of the clergy, but he nevertheless took a risk. Through Duccio’s legacy, people began to really think about what it means to be young, how youth relates to age, and what adults can take away from paying attention to and understanding younger generations. And there’s really no reason for us to be embarrassed by that.