I obsessed over the movie Alien and its entire world as a kid. And, moreso than anything else, that’s what the impending release of Alien: Isolation means to me: an excuse to revisit that world. It was—is—transgressive, scary, and strangely beautiful. The sequels have their merits—James Cameron’s full-bore action flick Aliens (1986) smartly avoids rehashing its predecessor, but David Fincher’s Alien 3 (1992) and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Alien: Resurrection (1997) serve mostly as footnotes to careers that have gotten (slightly) more and less successful, respectively.

But Alien contains multitudes. There’s grace to it, empty space that allows the imagination to thrive. You can’t, in the words of the film’s ruthless villain Ash, help but “admire its purity.” It hints at a massive future world, interstellar mining companies and androids that can pass as human, but leaves it all flickering at the margins. The alien itself is presented without explanation; there is an egg, and inside that egg is a monster.

Concretely speaking, Alien is Michael Myers as a penis-headed carnivore dripping with semen, stalking six humans through a haunted-house spaceship before meeting defeat at the hands of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley. But it’s also Forbidden Planet (1956) and Planet of the Vampires (1965) and EC Comics and The Thing from Another World (1951)—writer Dan O’Bannon said he “stole [the film] from everybody.”

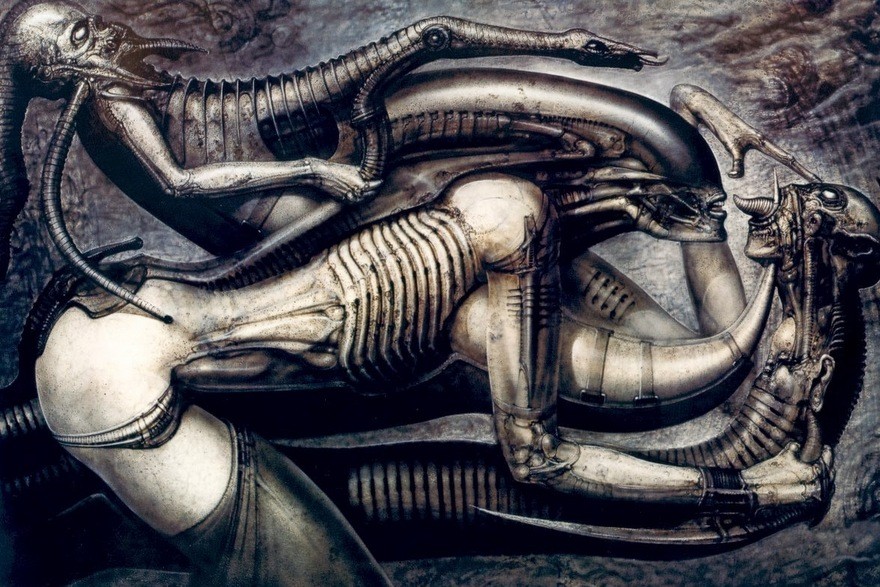

And then O’Bannon and eventual director Ridley Scott got damn near everybody to work on the thing. Alien’s improbable constellation of collaborators was left over from Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ludicrous, failed Dune adaptation, which brought O’Bannon, H.R. Giger, Chris Foss, Ron Cobb, and Moebius into each others’ orbit. Giger, in his monomania something like painting’s own H.P. Lovecraft, was obsessed with what he called “biomechanical” surrealist tableaux—all sensual lines offset by awful twisted organic-metal fusions and genital imagery.

Yet perhaps Giger is too much a part of our collective unconscious to shock any longer. After Dune imploded and Alien exploded, he did album art for metal legends Celtic Frost, Danzig, and Carcass. Aliens’ indelible queen design was handled by James Cameron himself: Giger’s next big film project was Species (1995), a film that literalized the monstrous feminine implicit in Giger’s art and launched an Alien-esque string of sequels, if Alien had been shitty, and its successors exponentially so.

The Species design—admittedly cool—looked extremely Alien-esque, which, of course it did, but it only illustrates how universal that original “xenomorph” became. It went from sui generis in 1979 to “Gigeresque” 15 years later.

The flip side to Giger’s metal-flesh eroticism—what was truly alien about Alien—was the rough-and-ready design of the Nostromo freighter, done by Chris Foss and Ron Cobb, as well as the distinctive Moebius-designed puffy spacesuits worn by its crew.

The apocrypha swirling around the film could fill libraries—did you know Ridley Scott wanted to be the John Ford of science fiction (and, briefly, it seemed like he could do it)? Did you know that the fledgling partnership of executive producer Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon also gave us Paul Verhoven’s Total Recall, eleven years later? Did you know?

//

Alien: Isolation knows. It knows all the nerdy details, but also knows the lore of Alien is as demystified as the creature itself, as Giger, as all of it. The allure of the film, though, what endures about it is that textually it offers so little: the lore of Alien isn’t the lore of Alien, it’s the lore of making Alien, all behind-the-scenes stuff that fans gobbled up in the pre-lavish DVD box set days in an effort to make sense of this nasty, fleet thriller.

Textually, Alien is sensual, frightening, foreign: Giger’s designs work against Scott’s perfectionist visuals—fascinated with texture and light—to create unnerving tension throughout, and the deft characterization of the script grounds it all in some kind of reality. Subtext lurks in every corner; Ripley as feminist heroine, the alien as rapist, the cynical joke that the creature is more valuable to the characters’ employers than they are.

The film is eerily quiet; in its pace, which luxuriates in graceful tracking shots along strange interiors and the overlapping Altman-esque banter of its workaday cast before ramping abruptly into scare scenes with whiplash editing, and in its volume. Jerry Goldsmith’s score begins as faint metallic clamor over the opening credits before eventually unfolding into an awesome (in the “wonder” sense, not the “dude” sense) theme, deployed tastefully. The sound design creeps carefully when it’s not abrasively loud and atonal.

Its moments of violence resonate all the louder for the contrast: the infamous chestburster scene, of course, still impresses with its semi-improvised verisimilitude, a Giger-phallus thrusting its way out of actor John Hurt’s chest and the rest of the cast unaware they were about to be covered in blood. And the alien’s final victim, perpetually scared-shitless Lambert, is dispatched in a horribly suggestive bit of montage, skirting some sort of awful violation: we see nothing, only hear her screams via intercom, but Ripley’s choked reaction on discovering her body is enough.

But how to make this all fresh again? Those kills are “tame” by the standards of the 80s, let alone today. The pacing? You’d put a teenager to sleep with this one. How to open Giger’s Necronomicon and stare agape at images unlike anything you’ve ever seen before?

The answer, surprisingly, is to retrace Alien’s steps.

“That first film is so rich, there’s so many different aspects to it,” Al Hope—the creative lead for Alien: Isolation—told me. “For us the first stage of development was a deconstruction, taking apart what those guys did. We knew we had to build new spaces—the movie’s only 116 minutes long—we needed to have hours and hours of content. We had to really understand what made Alien feel like Alien.”

I named my dog Ripley, so Hope is speaking my language. He says he’s a “survival horror fan, full-stop,” but Isolation is drilling down hard on Ridley Scott’s Alien and only Ridley Scott’s Alien. When I ask if there’s going to be any messing with player perception a la Silent Hill or Eternal Darkness, his response is already familiar.

“We take our cues from the first film.”

Fair enough. We’ve had a lot of Aliens games, but virtually no Alien games, I point out. That is, plenty of run-and-gun shooters but no tense, confined survival horror experiences. Hope, diplomatically, expresses his love for all Alien-related videogames but also says that “to me, it was all about what it would actually be like to encounter that alien and try to survive against it. A game about survival, not about killing.”

It seems counterintuitive to attempt any recreation of the Alien magic: after all, Cameron’s Aliens is always praised for its action-oriented spin on the material, the implication being that going back to the Nostromo would yield nothing but diminishing returns.

But what if that’s wrong?

What if we need to trace Alien—or the experience of Alien, the extratextual baggage that places us in that 1979 headspace—back to its root?

In La Dolce Morte, Mikael Koven’s comprehensive study of giallo, a cycle of psychosexual 60s/70s Italian slashers that were hopelessly in love with style, he posits giallo not as a genre but as a filone. Italian for vein or tradition, filone denotes giallo as a sort of branch of horror and crime, “a cluster of concurrent streamlets, veins, or traditions” that build on themselves ritualistically.

Alien: Isolation is a filone of Alien, in that it has wound its way through thirty-odd years of film and videogame history, accruing bits of other works as it went, and returned to that incipient moment in 1979 as if time-travelling. It has knowledge of where things went wrong, and has studied how they were done right the first time.

It is the ritual of the xenomorph and the human, seen with fresh eyes.

//

Al Hope tells me the game is about “the reality of what’s happening right now.” Moment-to-moment, you’re matching wits with Giger’s original alien, brought to life via layers of procedural animation “crossfading over each other depending on what decisions the AI is making.”

The team at Creative Assembly had access to a staggering three terabytes of Alien archives, the kind of figure that you’d expect from like documentarians studying ancient Egypt. But that’s the scope of this project, a reverent, near-archeological deep dive into 116 minutes of film. Hope says they wanted the game’s space station to feel like turning a corner on the Nostromo set and finding a new room. They recorded animation playing off VHS on meatspace CRTs while diddling the tracking knob to get—well, to get a tiny morsel of their videogame to look period-accurate. That’s how fucking granular this thing is getting, poring over the specifics as if recreating the film in pointillism.

As someone who, again, named their dog Ripley, I felt it necessary to personally thank Al Hope for bringing this to life.

Alien: Isolation aims to do the impossible: to make Alien terrifying again. After toys, games, costumes, parodies, sequels, spin-offs, team-ups, and generally Star Wars-level Big Thing-ness I’d begun greeting new Alien stuff with disinterest and even some bitterness: Ridley Scott himself misapprehended the allure of Alien as “Where’d that monster come from?” and whiffed with Prometheus.

It seemed plain as day that the xenomorph was as tapped out as Michael Myers or Hannibal Lecter, pinned like a dissected frog beneath hot halogens, not a speck of shadow left to conceal it.

Turns out all we needed to do was turn out the lights.