In the preface to his early 18th-century translation of The Iliad, Alexander Pope outlines the difference between it and The Aeneid:

“Homer makes us hearers, and Virgil leaves us readers.”

What does Apotheon do to us? It’s the question I’m asking myself as I bring a sagaris down onto the head of an unnamed enemy, its sharpened edge opening up a surprising fountain of blood, an anguished scream that reaches on for a little longer than could be comfortable. Behind his corpse arrives another enemy who looks identical, ready to try and cut me to pieces. I dispatch and dispatch and dispatch; that is, to say, I murder.

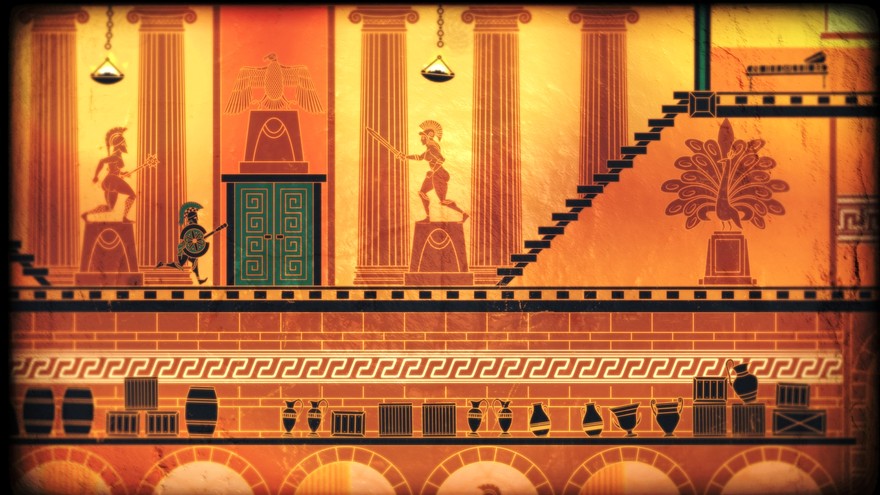

This is all atop the backdrop of painted pottery, their gorgeous figures brought to life amid columns made up of intricate lines. I hold my breath through the deep darkness of the painted-blue sea of Poseidon’s domain; I listen to the pleas of lost souls in the the sickly green hues of Hades’ underworld. In the forest of Artemis, massive, straight trees painted an inky black stretched upwards towards some proto-heaven, while deer and hunters frolicked amid naked satyrs, their delightfully erect penises curved upwards in awe.

The translation from urn to game is nearly flawless. Everything and everyone looks and acts just as though the figures of Grecian urns might, their limbs and movements more marionette than natural. Cyclopes are staggering in their size as they lumber towards me, their spear thrusts raining down in arcs. Triumphantly crafted thighs, butts, and pecs are everywhere, each specimen a faithful tribute to a medium where everybody is sculpted like a god. And over and over again, the flawless bodies of my enemies crumple to the floor.

If ancient Greece was a place of anything but war, Apotheon doesn’t seem to care. The way in which I’m allowed to interact with its beautiful, painted world is defined by the harsh objects of my inventory: swords, spears, axes, bludgeons. Bows, javelins, slings. Apotheon wants me to pick its world apart, and I do: I dance through Ares’ blood-filled arenas, climb towards Zeus by felling winged servants. Agoras populated by civilians quickly turn to chaos as guards begin to chase me through the streets, and people who I couldn’t interact with before are suddenly fleeing from me and the general area, our relationship essentially unchanged.

In a game filled with so much bloodshed, it’s the non-violence that stands out the most. Deep within the underworld I navigated dark cave-mazes by remembering pictographs. I once traversed three massive, concentric circles as they spun in Athena’s dizzying maze. A sea chart helped me navigate a ship through the pointed curves of the ocean. Even when Artemis and I took turns hunting each other as deer the game shone, because this was an adversary as painted through an interesting lens. Apotheon draws strength from the named characters developed in mythology, deftly contorting their blueprints to a matching purpose within the game.

But it’s the unnamed masses that make up all of the space in-between, and I’m not so much one of them as I am their conqueror: violent and unyielding. I seek out chests full of armor, weapons, and health potions, and anybody that stands in the way or near them will probably die.

Apotheon can be understood as a tale of revenge, and in this way, its bloodthirst is put into context. Violence bore our story—that Zeus has grown tired of mankind—and violence will carry us out of it. But for such careful attention and homage to a timeless period of art history, Apotheon often feels only skin-deep, as though the containers its style is drawn from never had other purposes, or never depicted anything besides war. In truth, they were jugs, cups, vessels, and they show not just bloodshed but foot races, weddings, celebrations.

Pope was alluding to Homer’s attention to the way different characters speak how their accents, upbringings, and personalities filter into language to create dialogue that is faithful to their sources. Virgil, instead, Pope claims, wrote less his characters and more himself: the author filters through the mouthpiece, is less authentic to the foundation. Even through a heavy bias, Pope makes a point: there is virtue in faithfulness to a source material. Apotheon appears at first a careful study as a big beautiful tribute to an art-style, but the homage rarely dips below the surface of the urns that inspired it. What are left are interactions that only serve in antithesis of its careful creation. Apotheon wants to make us citizens, but it ultimately leaves us tourists.