The best poetry alludes to a kind of magic. After all, as one classic tweet had us recall, the act of reading is to “stare at marked slices of tree for hours on end, hallucinating vividly.” It seems a bizarre activity when worded as such, but it’s the truth, as the power of finely tuned stanzas is enchanting. They can transport us to other places, acting as a catalyst for imagination, emotion.

A less graceful method for this transportation, you might argue, is videogames. They, too, take us someplace else where we can play in ways we typically cannot. Rather than solely using the potency of words, the videogame recipe is one of interaction, visuals, and sound. With this comparison, Emma Lugo’s ambition to bridge the gap between poetry and videogames doesn’t seem so far-fetched. In fact, it can be swallowed as an act of logic to assume that the two mediums could link hands, and with only the slightest of pushes.

But Lugo is made of more than ambition. She has achieved. With a piece of software she calls Astaeria, Lugo has married her favorite poems with procedurally generated virtualscapes for us to explore. The words becomes worlds. At its menu, it gives you a selection of poetry to choose from, including classic entries by Sylvia Plath, Lewis Carroll, and T.S. Eliot. Next to these titles, rather handily I’d add, is listed a duration in minutes, so you know exactly how long it will take to experience the world inside.

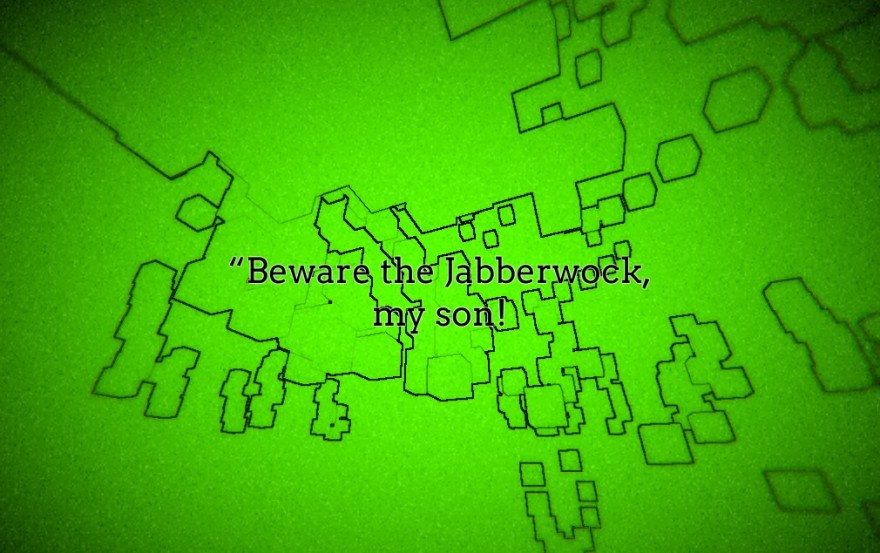

Beyond that interim, each poem you select then billows into a surreal world of vivid colors that wash over the screen like waves, changing in hue as if a psychedelic tapestry. The solid parts of the world that you stand and jump on are geometric structures that curl up to your feet as you step forward, almost as if you’re looking through a fish-eye lens. All the while, the verses of the poem appear in order for a few seconds at a time at the screen’s center. Eventually, the world crumbles, whole towers and staircases of cubes falling away as the words take you to the poem’s end.

Without the knowledge of how this virtual world is assembled, Lugo’s effort to tie poetry and videogames may seem perfunctory. It appears clumsy: the text of a poem is overlaid on a videogame world—where’s the great marriage of mediums in that? But it’s more of a cocktail than it first appears. “The random level generator seed is set to the hash of the poem, and each tall, cubic structure corresponds to a line in the poem, with each cube component being sized according to a word in the line,” Lugo explains.

So it is that the poem takes a physical form inside the software. Reading the words as you wander, you can imagine the structures as arches of stone, lakes of voidspace, and caves where creatures corral for warmth. Whatever the poem triggers you to hallucinate can dress this bare bones geometry. If you’re reading Lord Dunsany’s poem Charon, about the ferryman on the River Styx, perhaps you’ll see the endless drops all around you as the deathly river itself. Or maybe the environment twists into fingers of rock where an unspeakable creature lurks if you’re experiencing Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky.

It makes sense that Lugo should leave detail out in this way. Poems do too. What’s important is that there’s space left for us to fill as that’s where our mind expands the most. Take one of the most powerful short poems as an example: it’s Nobuyuki Yuasa’s translation of Matsuo Bashô’s famous Old Pond haiku, and it goes like this:

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond,

A frog jumped into water —

A deep resonance.

You can purchase Astaeria for $5 on itch.io.