One of the most curious aspects of the recent cultural wars in the gaming community has been the preciousness over what, exactly, merits the “videogame” label. Reactionary games like the defensively aggressive Hatred uses the language of returning to a more “pure gaming pleasure,” while placing on the other side of its “pure gaming” spectrum the games that are “polite, colorful, politically correct and trying to be some kind of higher art.” It’s an odd dichotomy to make, to say the least. For one thing, it sounds like the main grievance games like Hatred are addressing is that some people have the audacity to try and make “some kind of higher art” out of this thing they love. For another thing, it’s a dichotomy that presumes the existence of some sort of official metric for measuring the “purity” of a gaming experience. Like games are meth. Or like we live in a world where the equivalent of a videogame sommelier exists, and Gone Home simply scores much too low on the brainless-violence-to-narrative ratio to even peripherally be considered a “videogame.”

It’s a ludicrous dichotomy because it makes it sound like the ancient and multi-varied craft of game-making only started somewhere around the time that Postal came out. It assumes this centuries-old and universally human activity, in its “pure” form, must be irrelevant entertainment rather than instinctively productive play.

The Ruin Jam, a celebration of the totally real and systematic assassination of the “pure gaming” experience, was a jam “open to anyone and everyone who has been, is being, or plans to be accused of ruining the games industry.” Among the criteria for submitting an entry that effectively ruins the “pure gaming experience” are games that read as a “criticism or satire of existing game franchises,” and where the protagonist is “not able to jump, shoot, or be killed.”

From its very title, Alice Maz’s Average Maria Individual denies the traditional male power fantasy that so transparently defines what is considered a “pure gaming experience.” As a left side-scrolling “empathy fantasy,” Average Maria Individual continually subverts player expectation because, as Alice explains, “what better way to ‘ruin’ video games than to reimagine Super Mario Brothers, arguably one of the most iconic games ever, as a walking simulator about feelings starring a queer woman.”

When people talk about a “pure” or “traditional” game experience, what they often mean is the sensation of being the sole agent in a passive world, or as Alice puts it, “worlds created to cater to player narcissism over which they can exert total control and mastery.” In these player-centric worlds, NPCs are either enemies to be conquered, or objects to be manipulated and used in order to progress. And while a world of mastery may be more appropriate for games like Super Mario, which are according to Alice “essentially about manual dexterity,” Alice instead aims to criticize how “a lot of modern games with more ‘narrative’ aspirations continue to use their NPCs solely as enemies, signposts, or rewards.”

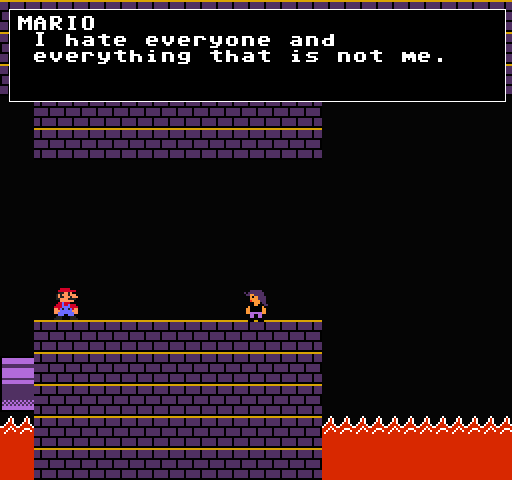

Rather than creating a word that exists solely to serve the player’s ego, Average Maria Individual forces the player to be “an interloper on [the NPCs’] space, who must conduct herself accordingly.” As a mirror of “the experience of a lot of marginalized folks in mainstream society, the game world is meant to be an idealized version of that dynamic,” causing an environment where “throughout much of the game, you’re at the mercy of those more powerful than you, although they treat you with love and respect as long as you’re willing to do the same for them.” While every impulse in your body might be shouting at you to be mistrustful and kill the Great Demon King (i.e. a Slim Fast version of Bowser), the only way to “conquer” him is to realize that he isn’t “an ‘enemy,’ just a person with feelings and concerns.”

While the power fantasy template for videogames always paints you, the player, as the hero and sole agent over a passive world, Average Maria Individual both strips the player of all power and forces her to question the presumptions behind the nobility of “saving people.” Again and again, NPCs who are supposed to be enemies demonstrate kindness and even despair towards you. The central question that fuels Average Maria Individual comes down to: can you really be the hero of a world enslaved to your every need? What does being a hero even look like in this context?

“Heroes: people who think they’re the only ones who matter,” answers the NPC who’s been serving as the player character’s reward for being such an awesome savior since 1985. While games like Hatred aim to bring back the “pure gaming experience” by continuing to provide worlds built and dominated by an overpowered player protagonist, Maria is left at the mercy of almost every individual she meets. Since her “jump is essentially powerless, she traverses the world not by running and jumping, but by walking and speaking—her dialog choices (made with the same key as jump) determine whether she will doom herself or be allowed to advance.” In fact the player can go the whole game without jumping once, and still beat it with flying colors.

Your ultimate goal in Average Maria Individual is to provide some relief to the long-standing tyranny of the “traditional game” hero. You don’t get rewards for taking what is “rightfully yours,” but instead by asking the questions that unlock the NPCs tortured lives. I’ll try not to spoil the ending for you, but I can confirm that at least one jump is absolutely necessary to complete the game successfully. And, in the spirit of ruining games and all, it’s an action done not for domination, but out of love.

You can play Average Maria Individual for free on Windows here.