Malebolgia begins with the most famous phrase of Dante’s Inferno, the first part of his sprawling epic poem detailing a personal journey from hell to heaven. “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate.” Abandon hope, all ye who enter here. Along with the title, which is taken from the Italian name for the eighth circle of hell, where hypocrites and frauds are punished, this quote sets the player’s expectation for Malebolgia through reference. This is a game interested in suffering, damnation, and, perhaps, redemption. We’ll see about that last one.

When the game begins, you awaken in the titular Palace Malebolgia—a sprawling, late Victorian mansion hemmed in on all sides by blizzard and shadow—as an old man named Leopold. Leopold is styled after an early 20th century noble, with a pointed hat and a well-coiffed beard. There is a key on a nearby table, and not far from there is a locked door. Aside from some basic primers with the controls, the player is given very little other guidance. No more is needed, really. Make like Dante and have a look around. Unlike Dante, however, there is no Virgil to guide you, and this is not merely a tourist stop. You live here now—welcome. It’s even more miserable than you expected, though, sometimes, when the demons you’re about to face slink away, it’s almost as fascinating.

Dante wrote The Divine Comedy in a style called terza rima; literally, “third rhyme.” It’s an interlocking structure of repeated, three-line rhymes, of the pattern a-b-a, b-c-b, c-d-c, etc, etc. Each stanza references the previous one and looks forward to the next, orderly and interlocking like the Great Chain of Being, or a rosary prayer. It’s also a show of virtuosity and dedication on the part of the author. As his literary self is working out his salvation with fear and trembling, he’s working out the rhyme scheme.

It’s a difficult balance to manage, and an even harder one to imitate. A few poets have tried, including Milton and Shelley, but it often comes out overly mannered and artificial, and for English poets it’s especially difficult, as English has many fewer rhyming words than Italian. It’s hard for me to read terza rima outside of Dante and his Italian forebearers without imagining a muscle stretching to the point of a tear, pushing itself just a bit harder than it can handle.

Malebolgia is a game that tries its own form of imitation, and the strain is just as visible here. While the aesthetics draw liberally from a mixture of the occult and late Victorian sensibilities, the gameplay pulls openly and deliberately from Hidetaka Miyazaki’s oeuvre. Gaming might not have a Dante, but we do have the inescapable spectre of Dark Souls. Malebolgia paces out the exploration of its titular palace with combat encounters that hit all the familiar Souls notes, with high-risk-high-reward encounters that prize slow, deliberate melee combat, focused on finding places to fit in heavy and light attacks in between the enemy’s own onslaughts.

On face, this isn’t a terrible idea. The Souls games have always had a purgatorial subtext, and the trials and tribulations of punishing, tense encounters with the palace’s demonic denizens seem like an ideal way to add an experiential dimension to Leopold’s journey, which, as you probably already guessed, reveals that Malebolgia is a vision of his personal damnation. In practice, though, it’s a strain that the game can’t quite handle.

See, the structure of the combat is there, but so much of the substance isn’t. Fighting in Malebolgia is Dark Souls in rigor mortis. Character animations are stiff and unresponsive, and controlling Leopold manages to feel both sluggish and weightless. The only weapon available to Leopold is a halberd limited only to up and down movements that can’t adequately respond to the variety of abilities enemies display, and attacks that didn’t seem to quite connect still did damage far more frequently than I was comfortable with. These fights are made even more punishing than seems necessary with an old-school save point system that scrubs progress made between the last save and the time of death, and by offering no way to heal during combat.

The style of gameplay that Malebolgia is going for, which relies on challenge, only functions if those challenges feel surmountable in a reliable way, if the player feels like success is reliant on their performance. Here, success seems reliant on getting the game’s finicky systems to play nice with your inputs, figuring out the right berth to give attacks that seem to overreach their animated range and making sure you don’t move out of lock-on range, because when you do Leopold puts away his weapon and can’t attack altogether. The demands of the game’s combat seem at odds with the systems put in place to carry them out, and the results feel like a pale imitation of finessed art, terza rima left to a hand that isn’t working with the right language in the first place.

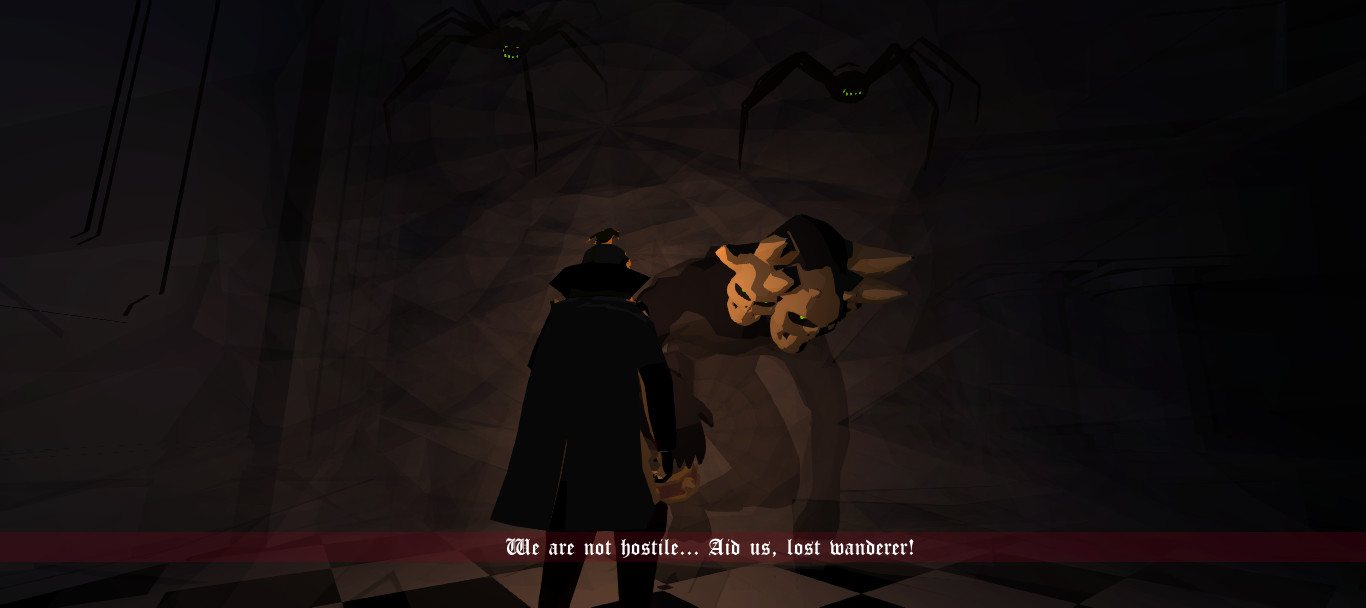

When the combat slows down, in the too-brief lull between boss battles, Malebolgia feels like a hell worth seeing. Lepold’s torch provides a flickering glow to the unused luxury around him. The web of a massive spider catches the light prismatically, shimmering like the edges of a kaleidoscope lense. The spider, rendered with eyes arranged like a grin, just watches you. The palace is rendered with a cartoonish crispness, a minimal cel-shaded look that imbues the world with just enough beauty to be truly haunting. The designers of Malebolgia seem aware that rendering something grotesque in a cartoony style only serves to make it more frightening, and they use it to great effect here. Nondescript dead bodies, simple white husks, lie abandoned on the floor while three-headed demons watch over them. A winged beast with cold, black eyes lurks on balconies and in empty hallways, disappearing when you get too close.

The Inferno’s enduring power lies, among other things, in the enduring fascination of taking a tourist trip to hell. It’s an allegorical look into the psychology of guilt and Dante’s own sense of justice, and he weaves those together into a place that manages to feel surprising and alive. So much of it is cliche now, but reading the poem itself reveals these ideas—a broken gate of warning, a cluster of traitors frozen at the center of the world—as vivid.

Malebolgia is clearly taken with those images, and attempts to translate them into a new setting and a new medium. It’s all there on that opening screen. Abandon hope, all ye who enter here. And it captures that spark, now and then, offering a simplified, exploratory version of that journey. But without the dexterity to give its gaming forebearers the same level of faithfulness, it ends up being hellacious for all the wrong reasons.