What is a neighbourhood beyond a collection of functions such as greenspace, housing, shops, and schools—figurative building blocks that can be strung together to build a functioning environment? The neighbourhood-as-collection-of-blocks metaphor appeals to videogame creators and audiences because it is an easily digestible abstraction and one that can easily be mapped onto basic game mechanics. This is how Sim City eventually bequeathed games like Oskar Stålberg’s Brick Blocks, in which you extruded a block of flats out of a base grid. Now this variant on the venerable city-building genre is getting beautified in Jose Sanchez’s Block’hood.

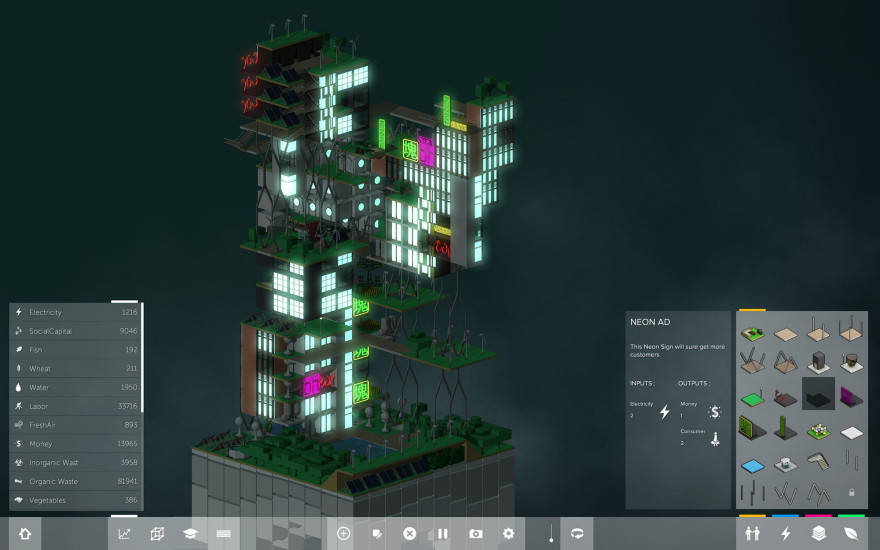

Block’hood, which is due to be released in late 2015, starts with a base grid that cannot accommodate all the functions you’d like your neighbourhood to offer. The game is not trying to make a deep point about the scarcity of land, but this state of affairs does make building upwards a necessity. And so you build up, stacking farms, schools, and factories.

Block’hood will initially offer “80+ building blocks,” though Sanchez promises “the library of Blocks will continue growing even after release, adding to the experience of the game and allowing you to design the city you always dreamed of.” The resulting neighbourhoods can be used in a variety of modes, including a research mode that joins Polynomics in offering itself as a tool for experimentation and “challenge mode” which sets goals for your neighbourhood and leaves you to figure out how to meet them.

(Because Block’hood is a polygonal pastel cluster floating in space, this is the moment when, as a professional videogames journalist, I’m legally obliged to compare it to Monument Valley. For fear of having my membership in the shadowy videogames cabal cancelled, I’m also obliged to say that it is the Monument Valley of something-or-other. Let me therefore declare that Block’hood is the Monument Valley of utopian tower cities, and now we can get on with our lives.)

The net result of Block’hood’s construction is something that looks eerily like an architect’s rendering of a forthcoming luxury tower. Indeed, “vertical city” is a common designation for architectural undertakings. Nevertheless, it is not yet clear what the term “vertical city” really describes. Literalists might imagine the vertical city as a sprawling urban environment that was cut up into tranches that were subsequently layered atop one another. For reasons of land scarcity, that might one day be the case, but that day has yet to come. Until then, “vertical city” will function as a mere euphemism.

To wit, feast your eyes on De Rotterdam, a “vertical city” designed by Rem Koolhaas’ OMA. Situated in the centre of Amsterdam, it resembles a collection of skyscrapers that have been stacked atop one another, which is possibly the least subtle visual metaphor for the vertical city. According to The Guardian’s Oliver Wainwright, De Rotterdam houses “not just 70,000 sq m of office space, but 240 apartments in the block to the west, and a 285-room boutique hotel in the block to the east, sitting on a chunky plinth of conference facilities, car parking and restaurants.” Those commercial elements do not a city make, unless your vision of a city is largely devoid of democratic and social functions. De Rotterdam may allow for the coexistence of work and personal spaces, but its conception of public space is eerily limited.

One might therefore be inclined to think of Block’hood as an opportunity to realize the more utopian (and literal) dream of the “vertical city,” a place where you could conceivably live your whole life in a tower. Indeed, the game appears to have been built to enable such experimentation. Whereas the logic of other city-building games pushes for sprawling horizontal expansion, the constrained ground plane in Block’hood will guide you to the sky. It is nevertheless hard to escape the sense that this is a game that will allow you to build the rendering of a building that will over-promise and fail to deliver—the sort of place that is marketed as a “vertical city” but ends up being an investment vehicle for most of its residents and provides a “poor door” for its less wealthy tenants. Even the phrases in Block’hood’s teaser video—“envision your neighbourhood…create abundance…think ecology…avoid decay”—feel like Mad Libs with Bjarke Ingels.

In July, City Lab’s Kriston Capps declared “Jengaform” to be the “look of recovery-era multifamily architecture.” Like the game from which Jengaform takes its name, Capps writes that the buildings are defined by “just two factors: stacked and elevated.” These projects are not necessarily “vertical cities,” they are simply less sleek towers. “Stacked architecture makes sense for the city because so many of the development opportunities are infill,” Capps writes, “and architects can get more out of a small building footprint using various tricky cantilevers.” Capps was writing about Washington DC, but he could just as well have been describing the way Block’hood navigates space constraints.

It’s unfair to hold the political baggage of the “vertical city” or the aesthetic baggage of Jengaform against Block’hood. Yet the fact that these connections present themselves speaks well for the game, which appears set to engage with planning challenges as well as the state of architecture in 2015. Block’hood is the best version of all these ideas: A tool for building truly compelling virtual cities that presents them in a compellingly pastel manner. If only these architectural renderings corresponded with reality.