Every commercial industry has their hub, an identifiable locale known for innovation and productivity. At least in the United States, one town usually comes to reflect the singular vision of a diffuse, multifaceted thing: Detroit does cars; Hollywood does film; Nashville does country music. It’s a false reality, but the perception lingers regardless.

Videogames have yet to find their popularized mecca. At any given time, studios worldwide are working on the next best thing, from the hive of activity in the Bay Area to secretive hardware being tested in Kyoto. Students learning advanced techniques in Vancouver might move to Austin, Texas, or Montpellier, France to prove their skills. As games grow in complexity, the process of building them mirrors that effort; levels might be designed in a giant complex, while music is composed in someone’s childhood bedroom.

But only one city spans the entire lifetime of the medium. Modern games arguably stem from the first interactive software created in a computer lab on the campus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, just outside of Boston. Today, Boston and its surrounding cities host studios creating blockbuster spectacles like Bioshock Infinite (Irrational Games), connected worlds with massive communities like Lord of the Rings Online (Turbine), and downloadable, fast-paced fun like Go Home Dinosaurs (Fire Hose Games).

I talked to three local studios about living and working in Boston (don’t call it “beantown”) and why the future of games might just come from where it all began.

—

Chris Foster is Senior Designer at Harmonix Music Systems in Cambridge. He grew up south of the city in New Bedford, the whaling town where Melville’s Moby Dick begins. But he thinks of Boston as his eclectic, vibrant home. “It’s got a slapped-together feel I find appealing. It’s a city without a grid anywhere in sight.”

This lack of rigid boundaries provides inspiration for where to take the future of games. Harmonix is known for their pioneering work on Guitar Hero, Rock Band, and Dance Central; their next Kinect-focused venture, Disney’s Fantasia, fuses the music-making of earlier efforts with the physical interaction of more recent titles. It makes sense that such games would arise from a studio blocks away from both renowned music clubs and Microsoft’s New England Research and Development (N.E.R.D.) center.

Many employees are musicians themselves. The company even held the launch party for Guitar Hero 2 at The Middle East, a popular venue down the street from their office, where bands of employees played live music. Foster remembers a cover of Danzig’s “Mother,” when one of the unassuming coders took the stage. “He stepped up and just crushed the song.” The moment reminded Foster of how the musical background at the studio ties into the larger musical scene of Boston, each strengthening the other. Success blooms from surprising places, with recent phenomenons Minecraft and Angry Birds the equivalent of that unassuming coder belting out a gem. The next break-out may be lurking in the dense development communities in and around Boston.

–

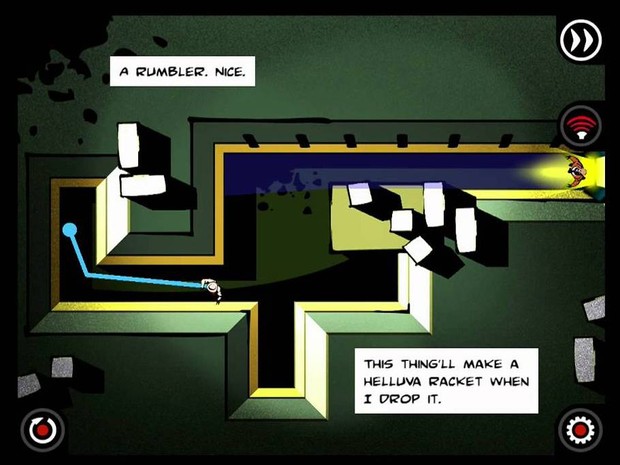

Christian Baekkelund was lead designer on Moonshot Games’ first mobile title, Third Eye Crime, releasing this winter on iOS. Moonshot embodies the largest area of growth in Boston-based games development: that small, independent team of an impassioned few who, due to the rise in mobile and its flexible, accessible marketplace, have the chance to create something incredible on their own.

“The indie game development community in the Boston area has exploded over the past few years,” Baekkelund wrote to me in an email. Indeed, when I visited Moonshot’s table at PAX East, they were one of dozens representing the Indie MegaBooth, a consortium of smaller studios who band together to take back some of the attention given to super-expensive mainstream blockbusters. Even though Third Eye Crime was picked as a local Indie Showcase title, Baekkelund says, they felt like one of a larger whole. Just a year prior they would have stuck out; now, the area’s indie success presents the double-edged reality of competition among peers.

And there’s plenty more candidates coming down the road. Baekkelund cites Boston as having a rich vein of “renewable natural resources”: “Boston is a big tech town and a big college town. There is no end of entry-level candidates in the area.” Every spring brings a new crop of graduates to the wild. And with new consoles dropping restrictions on indies, making it easier than ever before to publish your game, that vein of potential will not dry up any time soon.

–

Jason Haas was once one of these fresh faces. Now he’s a game designer and graduate student at the MIT Media Lab. He explains the churn of new and old faces with an analogy more at home in the Great Plains: “You have harvest season, and then winter. You sort of vacillate between the two. And that’s created a bunch of people who know each other very well.”

He also sees Boston’s relative smallness as a strength. We met at a small coffee shop in Somerville, ten minutes from Tufts University and a few subway stops from Harvard and MIT. Here you can pursue your passions, in a city that just so happens to host an international center of technology research and scores of esteemed universities.

“I worry that in a place like New York there’s a constant demand for thinking about money,” he said. “In the Bay Area there’s the possibility you get sucked up into Silicon Valley. While [Boston’s] not a cheap place to live, there’s enough infrastructure as well as enough smart talent that likes living here, which produces a pretty fun, playful community.”

Haas works with MIT’s Education Arcade, trying to use the technology and language of games in a way to foster learning. In 2006 they developed together with NBC News a learning platform called iCue: an online hub connecting current news stories with games and social networks. Though the venture failed, Haas co-wrote a book, The More We Know, with MIT professor Eric Klopfer about valuable lessons learned and the challenges of merging education with our increasingly interactive reality.

Haas also spent time in the improv comedy scene. Boston’s bred many a fine humorist, from Stephen Wright and Denis Leary to Jay Leno and David Cross. Game development is tough; to stick with the grind, it likely helps to crack a smile once in awhile. With a trace of a smirk, Haas explains how the area’s esteemed higher education can get in the way of progress, and in doing so outlines a formula for the way forward.

“MIT in particular has a lot of people with technical prowess and not a lot of… perspective, sometimes,” he says. “I came from a liberal arts background. I can use their engineering problems to solve people problems.”

Top Image via Bahman Farzad