One of the first things that Anne Ferrero says to me is that her new documentary isn’t “Indie Game: The Movie [2012] in Japan.” She tells me this as she’s aware that many people will assume that to be the case. But it’s not just a matter of a director looking to ensure that her potential audience isn’t misled: there’s a lot more to it.

Much of it is summed up by one of Ferrero’s interview subjects in the documentary, Alexander De Giorgio, the chief organizer of Tokyo Indie Fest. “I think it’s dangerous to try and compare the Japanese indie scene to scenes in other countries because they all evolved in different ways,” he says, “they all have their own strengths and weaknesses.” The documentary, called Branching Paths (subtitle: “A journey through Japan’s indie game scene”) constantly surfs this danger, and Ferrero seems aware of it, as she should.

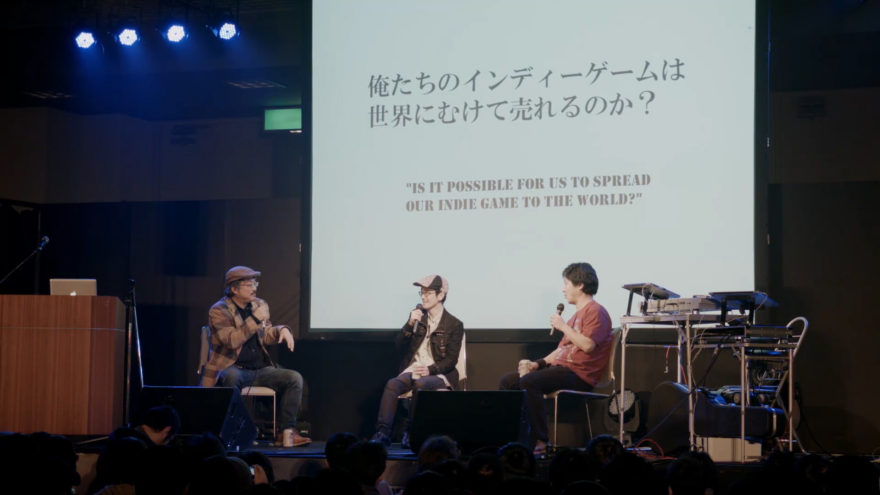

It starts out in September 2013, at the Tokyo Game Show (TGS), which is Japan’s biggest videogame-focused event. But this one in 2013 is significant as it’s the first after another event launched in Kyoto during March that year called BitSummit, which prompted the TGS organizers to host their own indie games area for the first time ever. Ferrero says that BitSummit 2013 “could be considered the first point of recognition of ‘indies’ in Japan”—that is, via the Western understanding of “indie.” And here we meet another point of contention, and another reason that comparisons to Indie Game: The Movie are discouraged by the filmmakers.

In Japan, “indie” is a new term being applied to its independent game creators, and it comes from the West. Its arrival in Japan, as depicted in Branching Paths, is the start of an energy that builds around cultural exchange between Japan and the West. The dominant notion by the documentary’s end is that, for Japanese indies to survive, they need to market their games to the West. This idea has arisen as Americans and Europeans move over to Japan to start their own studios, to start new videogame events and meetups, and to publish small Japanese games for Westerners that have a chance of standing out in an increasingly crowded sea of Western independent games. It’s all driven by a focus on economics, and the documentary does well in depicting how this rises over the two-year period it covers, and the structures that emerge to support it all in that time.

But the point is the word “indie” has a foreignness to it, and there’s a sense that it’s being imposed on the most marketable Japanese independent games and the people who make them. Before this, Japan exclusively used the word doujin to refer to its independent creators. And it’s not just those making games: anyone who is making music, anime, manga, or art in general for themselves, is referred to as doujin. Most of them are hobbyists and are seen briefly in the documentary at Japan’s famous Comiket (comic market), which attracts around one million visitors every year. Ferrero shows up with her camera at the Comiket held in November 2013, where she finds ZUN, who is probably the most successful doujin artist of them all. He’s famous for his Touhou series of shoot-’em-ups, which he’s been making for about 20 years now, and attracted a huge fan base in Japan who tirelessly create anime, fan games, manga, even Touhou-themed bands. “Taken as a whole, it might be bigger than the major consoles,” ZUN tells Ferrero of Touhou‘s spread. That’s not him boasting—he’s a meek man who doesn’t seem to be changed by his success—that’s just the truth.

ZUN captures the zeitgeist of what was happening around the Japanese independent games scene in 2013. He speaks of the uncertainty and doubt about how Westerners and the word “indie” are changing Japanese games. It’s a feeling that isn’t really returned to afterward in the documentary but resonates throughout. “There’s been a paradigm shift in how creators see doujin,” ZUN says. “It’s become less and less about making only what you love and enjoying the process. People want to succeed. They want to hit it big. In that way, I think doujin are turning into indies. I don’t really know if this is a good thing or a bad thing for doujin.”

Whether it is good or bad for doujin is never answered in the film. Instead, when Branching Paths is confronted by the split its title seems to refer to, it follows the one signposted “indie” rather than “doujin.” To wit, it takes what might be deemed the optimist path, the one that sees the Western influence on Japan as healthy. That’s not to say that it isn’t healthy, as there are many signs that it is, but it does leave the documentary with an unanswered hole of inquiry. The implication is that the Westerners seen mingling with and leading the Japanese scene are helping Japan to help itself. We see the effects of how these Western ideas have pervaded, such as crowdfunding, which is depicted only as a runaway success through the Kickstarters for the Mega Man designer-led Comcept with Mighty No. 9, and the Castlevania designer-led Inti Creates with Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night. What’s missed out in the documentary, which is no fault of Ferrero’s (it happened after her filming period), are the more recent troubles that Mighty No. 9 went through—extensive delays, disappointed players, and mediocre reviews.

Back in March 2012, during a Q&A after an Indie Game: The Movie screening, Fez (2012) designer Phil Fish said that modern Japanese games “just suck” in response to a question by Makoto Goto, a Japanese game maker. During BitSummit 2013, Goto spoke to Kotaku‘s Brian Ashcraft, who had covered the story of what Fish had said during that Q&A. “That was rude, sure, but I really want to thank Phil Fish, too, for what he said,” Goto said. “I think his remark really motivated Japanese game creators to work harder. I know it has motivated me.” You can’t tell by watching Branching Paths whether what Goto said has any wider truth to it. Are Japanese game makers any more motivated by what Fish said? Did they even hear him? There’s no evidence to answer these questions. Nonetheless, as a viewer who’s aware of this narrative, while watching Branching Paths there’s a sense that it’s documenting the echo of Fish’s words. But it’s not an echo that originates in Japan; it comes from the West.

Ferrero started making the documentary as it was the first time she had heard the word “indie” around Japan’s game-making scene. She was pulled towards it by Kimura Yoshiro, who she had met over a coffee in the summer of 2013, which was not long after he had left the “industry” to go independent with his new studio Onion Games. A year later, Koji Igarashi left his position at Konami and went the same path to co-found ArtPlay, Inc.. There was a taste of independent games as liberation in the air that older Japanese game makers wanted to pursue. Ferrero’s documentary focuses on this idea a lot and seems to suggest that the West is to thank for it. It doesn’t spend so much time capturing the struggle of Japanese game designers—older and younger—as they try to adapt to the Western practices being introduced to them. But what’s there suggests another, more worrying narrative.

“Shortly after Minecraft (2009), when indies seemed to become really popular abroad, many foreign companies contacted me, asking me to localize my doujin games,” said Nal of Japanese indie studio Edelweiss in the documentary. “Honestly, I think just succeeding in Japan is still hard. The biggest markets are still overseas. Once your game is well-rated abroad, then it seems Japan pays attention.” Nal has seen success in the West with games like Astebreed (2014), but he seems saddened that his games don’t see as much success in Japan, partly because Japan’s PC game market is still very small. Later on in the documentary, Ojiro Fumoto (aka moppin) recalls how some of his Japanese friends described his game Downwell (2015) as feeling very Western. It’s known that the game is inspired by Spelunky (2012) and sports many comparisons to it, which may explain these comments. Fumoto also says that his thinking may be influenced by the Western games he played while living in New Zealand in his younger years.

By its end, Branching Paths depicts Fumoto and Downwell as the one Japanese “indie” game that might bring the Japanese independent scene to the rest of the world—it’s built up as the breakout hit that might revitalize the entire country. But Fumoto, who is the last talking head in the documentary, downplays his own success to finish off by saying that he wants to focus on Japan and building up the independent game scene there. He doesn’t say it directly, but it feels like he’s implying that he wants to focus more on fostering a Japanese-ness in the local game scene, separate from the Western touch that has helped him. This Japanese-ness presumably already exists in the doujin creators who haven’t embraced Western “indie” persuasion. The challenge seems to be convincing the rest of the world that it’s worthwhile. But you have to wonder if that’s what they want to happen.

As ZUN said, the notion of “indie” in Japan is very different to “doujin.” Indie is a Western appropriation that seems very much driven by money and becoming a full-time game maker. It’s all about marketing Japan to the globe. But the few doujin artists making games shown in Branching Paths say they’re happy working on their games in the evening, after work, taking as long as 10 years to create what it is they want, just enjoying the process. Some of them, such as Keika Hanada, creator of Fata morgana no Yakata (2010), have even managed to hit it big in Japan’s PC market all by themselves. It goes some way to challenging the underlying message of Branching Paths that West is the way to go.

“Right now I think we value entrepreneurs and those who make it big the most,” said Inafune during his interview. Inafune criticizes the Japanese mentality which he says values its salarymen more than its artists. The worry is that “indie” in Japan might reinforce that, valuing those who can make money and find success with their games overseas more than the other successful artists making games for their own people. The impression that Branching Paths leaves is that the independent Japanese studios who do find success tend to have Western designs and are picked up by Western publishers. Or, quite simply, are a Western team living in Japan—these, especially, are given a lot of air time in Branching Paths.

Recently, Sony has taken to hanging banners around Tokyo Game Show declaring that “PlayStation <3 Indies.” But is there any love for doujin? (Update: Ferrero replied to this: “Actually, there’s a Sony program for this in Japan called “Play Doujin!” which started in 2014. It’s one of the many many things I wanted to put in the documentary and has been cut to make the movie a little easier to understand.”)

You can find out more about Branching Paths on its website. It’s available to purchase digitally on Playism and Steam.