A storefront gallery space in New York City’s tony Chelsea neighborhood isn’t the first place you might expect to find a videogame, much less dozens of them being played at once. Last Thursday night, Postmasters gallery opened its exhibition “Play Station,” a show of artist-made videogames curated by Marcin Ramocki and Paul Slocum, with a free-for-all night of interactive art games projected on the gallery’s walls. Visitors could play as an ambivalent lumberjack in a side-scrolling environmentalist action game, participate in a trippy text-based adventure, or use a flyswatter to shoot at virtual insects on the attack.

The event was BYOB, which in this case stands for “Bring Your Own Beamer,” an art exhibition format invented by media artist and game designer Rafael Rozendaal that involves each participating artist carting a projector to a designated space and displaying their work on any flat surface they can find-floor to ceiling and anywhere in between. At Postmasters, rather than projecting animated GIFs or abstract video art, artists brought along their home-cooked independent games.

By 8 p.m., the gallery was packed with a crowd of volunteers waiting to test out the latest in art games. The term “art videogame” might bring immediately to mind connotations of obtuse difficulty, intentional confusion, and not very much fun. But what these games had in common, despite their different strategies and different formats, was their sense of fun—and fun in a more challenging form than a night spent on World of Warcraft or Call of Duty. The artists used their games to confront basic preconceptions of how we interact with videogames and what purpose games serve.

In Charlie Whitney’s Lumber Smash, a pixel lumberjack marches forever forward on a scrolling forest landscape, encountering tree after tree. Players press the spacebar to swing a tiny axe, chopping down tree after tree. Twenty trees chopped down garners one point. Sometimes acorns fall from the trees. That’s about it.

“It is a boring game, and it’s supposed to be,” Whitney said. “A lot of games these days aren’t that fun but you do it out of duty,” he noted, referring to repetitive massively-multiplayer online leveling and other arduous virtual tasks. Lumber Smash is as much environmentalist message as it is a critique of treadmilling. “You feel bad about destroying so many trees,” the artist said. “You want to fill up the meter, but you have no reason to.” Yet we go on pressing the button.

C. J. Yeh‘s piece Happiness x 100, created specifically for the exhibition, uses a webcam to let players control a floating Mario hat by jumping up and down. Above the hat is a classic Mario question block, and each time the hat hits the block, coins fly out and pile up on the sides of the game’s small monitor, accruing points. The points build up in jumps and skips, sometimes by a dozen, sometimes just three.

Yeh’s inspiration came from the “pure joy” he felt playing Super Mario Bros. in childhood, but the game also has another message: “How hard it is to achieve true happiness when you grow up,” he explains. Players “win” by hitting exactly 100 coins, no easy task, more up to luck than skill. “When you get 100 exactly, there will be a secret message that teaches you the way to achieve true happiness,” the artist laughed. Two people got to 100 that night, but they didn’t divulge the secret.

Projected high on the wall, James George‘s Shuttershudder is a competitive game that players have to take a risk to win. Part of his Antagonistic Apps series, the iPhone application forces players to disrupt the phone’s video by grabbing it and shaking as violently as possible. After the game starts, a shutter starts to close on the phone’s screen. The harder players shake, the slower the shutter moves, until it closes and the video stops. The last player still recording wins.

Shuttershudder “creates a system that provokes, encourages and explores” the downsides of mobile video. Instead of holding the phone as still as possible to avoid mistakes in the video, players embrace those same mistakes in their movement. When playing, “you transition from focusing on the image to focusing on the physicality of it,” George said. “You can’t have the video one way or the other.”

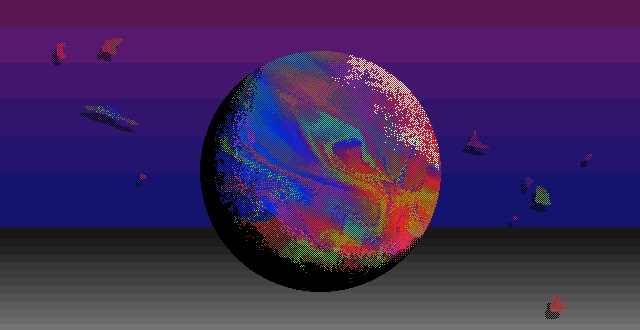

A loud thwacking sound heard constantly throughout the evening was Joe McKay’s Swatter, in which players rotated a hand crank to hit a table with a flyswatter, shooting bullets out of a triangle at cockroaches and spiders. In a quieter corner, Jeremiah Johnson’s Void Gaze rewarded players for making their way through a text-based adventure game that traveled through dusty attics, virtual landscapes, and glimpses of the infinite with swirling GIF animations in acid colors, like artifacts of ’90s cyberculture mixed with ’80s hair metal.

Near the end of the night, attention swung to a Super Nintendo showing a projected game of plain, old Street Fighter II. The artist had originally intended to warp the game with Game Genie, but the add-on glitched out. Instantly recognizable and playable, Street Fighter II was a beacon of shared nostalgia for the exhibition’s visitors. The presence of the game was also a reminder that videogames, art or not, are communal experiences at heart.

Image from Void Gaze