One of the first decisions I activated was whether or not I should give Duck a high five. Give Duck a high five? Is it safe to assume that there are no repercussions to “give a kid a high five”? What would the possible damage of giving Duck a high five be? Yes, that happened in one of The Walking Dead’s chapters, but it wasn’t a lynchpin that really sticks in the memory. What became of Duck and that high five! And yet, because of the common nature of Telltale’s Walking Dead games and their wrought decision tactics, it’s hard not to wonder, “What if something abhorrent happens because I gave Duck that high five?”

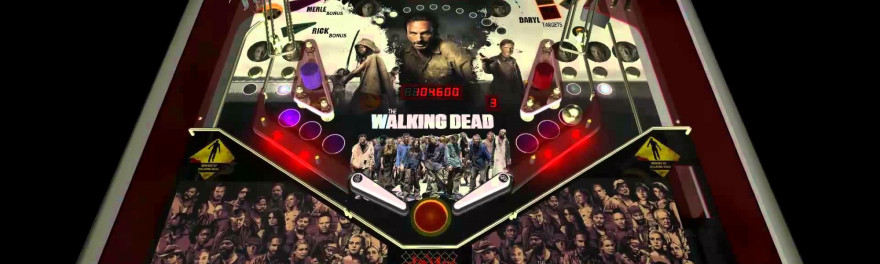

Had I been playing Telltale’s Walking Dead videogames, I’d be reminded of the context to make the responsible decision. The lead up and conclusions of giving Duck a high five v. not giving Duck a high five. But I wasn’t playing Telltale’s game; I was playing the videogame version of The Walking Dead pinball, which is itself part of Zen Pinball 2, and based on those Telltale Walking Dead videogames that are based on the comics. This is not to be mistaken with another Walking Dead pinball machine, which is non-virtual, based on the AMC show that is based on the comics, and recently moved into a veal sandwich place across the street.

The Telltale games were especially earmarked for their critical nuances. They followed the story of Lee Everett, who was constantly confronted with choices, often with no obvious good or bad implications, and sometimes with no “better” option to be had. The games emphasized that, when there’s no more room in hell and the dead walk the earth, it is a bad scene.

That emotional force overtook the series’ gore, which is why emotion has again become the philosophical prescription of Zen’s pinball recreation. There’s still zombie stomping, sure, but you more often need to scavenge for supplies or scout safe paths, the latter requiring you to avoid a walking dead (a ball with a ghoulish face) mechanically rolling from side to side.

Each mode begins with having to make one of the decisions from the games—albeit none with any more explanation than when giving Duck one up top, just sound bites of Lee yelling, or whimpering “I’m sorry.” One of the strangest bonuses is when you light “S-M-I-L-E” and the silver ball turns into a soccer ball, as Lee and Clementine kick passes to each other as refuge from their grim scenario. A humble guitar strums in accompaniment.

The physical machine doesn’t arm itself for those moral litmuses. There are a lot of Norman Reedus impressions, skull cracking and a bloated well walker on the middle of the playfield, that wobbles when you hit it like a dashboard tchotchke. That is not to say that pinball is incapable of narrative, but it’s more convenient not to bother.

If your reaction to a pinball machine has usually been more overstimulated than empathetic, then you have my understood sympathy. Obviously through the light show and loud noises, it’s difficult for a newcomer to know that each pinball machine is more than just ramming targets until points get good, that the best points have very specific criteria to meet, that there’s a path, often a difficult one, that can lead you to an even louder grand finale.

A pinball can tell a story, but it is a story in parts, progressed as each activity is initiated and defeated, inching the player towards the “wizard mode”—that is, the final chapter.

In Williams’ Junk Yard, for example, you’re trapped in a maniacal trash heap by Crazy Bob, trying to assemble a machine to carry you out of there. In Midway’s Who Dunnit, you’re a detective trying to narrow the killer down from four suspects; guessing who is and is not responsible is an actual mechanic of the game. The Machine: Bride of Pin*Bot has you watch an android evolve. The Steve Richie-designed Star Trek: The Next Generation machine has you voyage through a series of encounter, ranging from diplomatic nuisances with the Ferengi, to close calls with Cardassians, to locking horns with the Borg.

Pinball, much like the arcade games around them, tell a story through checkpoints. Both the beat-em-up version and the pinball cabinet for Hook will dissolve the Amblin entertainment into its set-pieces, though the pinball is more likely to include the baseball stuff. Pinball machines are obviously limited by their form, but by no means incapable.

The Zen Walking Dead machine, then, is a bit of an odd duck (not Duck). It attempts to echo the narrative weight of the Telltale games without re-enacting them. The decision then becomes an odd middle-route, making each tough choice a sort of moment akin to the moments the Johnny Mnemonic pinball decides to earmark, which includes bonuses based on car chases and confrontations that can only be stitched together by someone familiar with the source material.

Pinball is a form, especially in its digital frontier, begging to be experimented with. A lot of Zen machines are good—I think their recent South Park table is spectacularly loaded compared to what you’d get in a physical offering, and the Plants Versus Zombies table does a swell job at refitting the game it’s based on. But Plants Versus Zombies also isn’t as big a trial in nuance as The Walking Dead, aside from rotting corpse textures. Their attempt to make a pinball RPG, Epic Quest, left a lot to be desired. The upcoming RPG Rollers of the Realm should be interesting, though very form-breaking, as it doesn’t hang around a single playfield for extended periods.

Instead of recreating, this feels a little bit like mimicking, a sort of farcical contrast between what The Walking Dead games were capable of and what The Walking Dead Pinball machine would have to get farther away from its comfortable form to accommodate. The real-life Walking Dead pinball, which I think play-wise is less spectacular than Zen’s, at least doesn’t create this chasm-like juxtaposition by biting more brains than it’s prepared to chew.