Me and Brandon would jam. He’d come over with his Gibson. I’d be on a Roland MC-505. Though I have zilch musical knowhow, and had only played a drum machine drunk once or twice, it was raw. We had chemistry. The music came alive. We invited over a guy with turntables, got a guy on bass, wrote songs about girls we knew in high school. Then, a few weeks passed and I stopped hearing from them, only to find out they had been playing behind my back. (Obviously, they were jealous of my Sun Ra-esque power solos, but, like, whatever.)

With Rocksmith 2014, who needs them? Ubisoft San Francisco has created a suite of session musicians who are ready to rock out. The game’s artificial intelligence serves as your backing band. While this may seem too William Gibson to be true, let’s give them some credit. The original Rocksmith pulled off a similarly admirable task, showing plastic guitar prodigies how to master real electric ones. Now, they’re teaching machines to improvise.

While solid at running spell check, computers are pretty clueless when it comes to being impulsive, an important aspect of creativity. Thus, much of the work in the field of music AI is a collaboration between machinery and man. For instance, the jazz composer George Lewis has been performing for years alongside grand pianos controlled by software. Likewise, David Cope’s Experiments in Musical Intelligence mines unfound sounds from the concertos of Chopin and Bach, but with one caveat. The composer is an active participant. Otherwise, it’s hash.

Along the same lines, 2014’s Session Mode features a quartet of musicians that react to the way you play guitar. They do this extemporaneously and without plan. When I spoke to the guys at Ubisoft, the conversation was marked by a giddy optimism. “We can make it as good as any musician,” says Paul Cross, the creative director. Quite an impressive feat considering the difficulty of hardwiring the ebb and flow of sound. As the game’s audio designer Nick Bonardi explains, “If you try to make rules in music, there’s always going to be an exception. Music is so expressive that there really are no bounds.

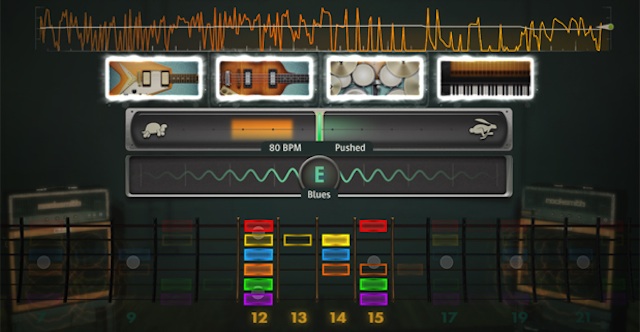

To capture this immensity, they created a flexible system that shifts snippets of sound in and out of the composition. Think of it as an autonomous DJ for samples and loops. Altogether, there are seventy-five instruments (guitar, drums, bass, piano, synths, kazoo, etc.) playing over a thousand prerecorded jams (in styles of rock, blues, metal, etc.). In the background, the computer is tweaking the mixer, adjusting on the fly things such as note length (4 bars, 16 bars, 32 bars, etc.), dynamics (forte, fortissimo, and so on), and effects (like panning). The intelligence impacts everything from the big picture (groove, tempo, root, and scale) down to tiny details.

Therein lies a problem. Multiply all that stuff by four band members—each following your lead and suggesting new ideas—and the complexity approaches warp speed pretty quick. So that your computer mates don’t rock you out of the room, the producers had to dial back what the band is capable of. (That said, turn up a knob and they will “pull out the rug from underneath you,” Bonardi says.)

Just because a computer can play the most difficult chords with ease doesn’t mean they should. “People practice guitar for years and years so they can do insane sweep picking stuff—EeewEeeewEeeeeewEeeewEeew metal stuff. Well, you can have a computer do that, no problem. You can map the craziest thing, crazier than anyone could ever play,” Bonardi tells me. The trouble is it sounds not only inhuman but absurd.

The team hit a paradoxical road bump: perfection was somehow undesirable. While guitarists struggle for years to become the masters of their axes, it feels off when the machine nails it time and again. “You can make it absolutely perfect, but it doesn’t seem real,” Bonardi says. “The more exact you make a computer, the more people question what perfection is.” That may be true, but it’s also deeply ironic. Session Mode is a tool to teach players how to play the guitar with others. It’s like an instructor telling you to play good, but not too good.

The team found themselves adding flaws to the computer’s behavior so that it sounded more like a group of guys jamming, and less like the Terminator playing thrash. For example, occasionally the tempo will wobble, speeding up and losing momentum as the jam heads in a new direction, as it’s wont to do when improvising. Though it may seem that us mere mortals are slowing down the machines, Bonardi tells me that that’s the wrong way to think of it—that the swagger actually improves the sound and makes the session more exciting.

For the sake of verisimilitude, extra effort went into giving Rocksmith a dash of sprezzatura. If you listen closely, this can be heard in the weight of the key presses, in fingers moving on the strings of a bass guitar, the clack of a pick. “There’s so much character and tone in the flaws,” Bonardi tells me. Your artificial Slash will unexpectedly hit the guitar neck and “it’s like OHHHHMM,” he says. And he won’t ever ditch you, unlike my slacker friends.

Special thanks to David Kanaga for assistance with research.