I’m not sure how and when the conventional wisdom in game development became that you should construct a game like a small, importunate dog that yips and paws at the gamer’s ankles in search of constant congratulation, but here we are. The unfortunate result of this thinking is, for instance, the dialogue in Rockstar games, which is showy and self-consciously literary, like it was written by foundering screenwriters trying to prove something to a Miramax exec who wouldn’t return their calls. You know Twisted Pixel’s games are “fun” and “irreverent” because they contain sub-Seth MacFarlane shock humor and aggressive, repeated breaking of the fourth wall. Jonathan Blow is the way he is.

This try-hard syndrome infects a lot of art, but it seems to torpedo an inordinate amount of potentially affecting games. I feel like I hit this wall a lot: I’ll be having fun solving a puzzle or anxiously stabbing my way through a dungeon, and my reward, when I emerge from the little hyper-engaged bubble games can put you in, is a three-minute cut scene that’s all melodramatic exposition or a block of text that proves someone in the writers’ room has read some Philip K. Dick. I often feel condescended to by games, wishing they would stop trying to impress me the way dipshit, full-of-themselves types try to woo prospective sexual conquests at college parties.

Let’s sympathize with the artist for a moment. Making a thing is hard, and because the creative process is like being dragged across god’s cheese grater, you might be tempted to try to get your money’s worth, make your art serve as a catch-all for every halfway smart or funny idea your labor has produced. This is something you should not do, because it will make people hate you, but it’s an understandable impulse. What an artist must grasp, if he or she wants to be of any use to anyone, is that reining oneself in, while sometimes painful, has the benefit of making you seem less eager to please and sharper of mind than you actually are.

Being good at something, paradoxically, often means not demonstrably trying to be good at it. Think about the way Louis CK’s jokes seem like he just thought of them while taking a shit backstage or the conversational incandescence of Jay-Z’s flow circa 2001. Even better, think about how casually Lucasarts’s Monkey Island series throws hundreds of ideas and gags at the player. Think about the first time you experienced Playdead’s Limbo, how the game refused to and then slowly revealed itself to you. You flaked out on dinner with some friends because you wanted to keep exploring its chalkboard hell. Great artists cooly manipulate the universe their art creates. You come to what they’ve built, not the other way around.

Candy Box 2 is the sequel to a modest, goofy project by a teenaged French computer programmer who goes by aniwey. The first game trickled out into the internet this spring and became something between a curiosity and a sensation: a one-day wonder.

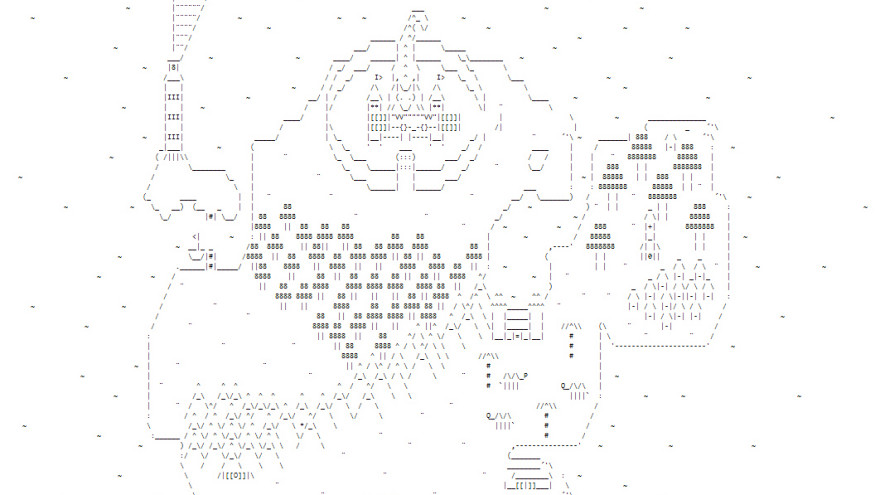

Candy Box 2 is more expansive—your character has, like, a health bar and stuff—but it’s still deceptively not much. It’s a free browser game with ASCII art that plays like it was conceived of and made in one blunted weekend. You collect candies, which are like money. You farm lollipops, which are also like money. Both things are alchemy ingredients. The dialogue is demented and reads like it was written by an enthusiastic seven-year-old. You fight camels and octopus monarchs and the developer himself. “Fight” isn’t the word, really. You try to run through them, while frantically pressing the “eat potion” button every few seconds. I feel a little like Steve Brule trying to explain this thing. You can get different swords.

What’s remarkable about Candy Box 2 is the way it un-ostentatiously reveals itself to be brilliant. It’s structured like one of those much-detested Zwinky games, in that it makes you wait as your currency accumulates. Whereas Farmville and games like it are cynical, often anti-player affairs, the effect of Candy Box 2’s waiting mechanic is that it permeates your day in an unobtrusive way. It’s in the periphery while you fire off emails or take a trip to the liquor store. You come back to it every hour or so, buy a better weapon, attack a primate wizard or a monster made of nougat. It’s a sharp blast of absurdity, made out of ampersands and em-dashes, which you occasionally give yourself over to for a few minutes at a time.

It’s also a funny game, not in the sense that it has lots of jokes, but because it’s presented so straightforwardly, like of course you can buy swords with candies and talk shop with helpful dragons. Candy Box 2 was developed by a Frenchman, but its sensibilities recall Japanese masterpieces like Little King’s Story and Jet Set Radio in that it is self-assuredly and willfully weird without feeling the need to impress its bizarreness upon the gamer. You can enchant a crown that makes your character spray blocky orange fireballs from every part of his three-character body. It’s delightful slapstick and also just a very useful enchantment.

Candy Box 2 may be another low-rent browser game with all sorts of technical limitations, but aniwey’s approach to game design is universally instructive. It’s an argument for laconicness and restraint, for making a game that’s thoughtful and smart and funny without assaulting the gamer with the fact that it is those things. It’s a lowbrow, frivolous-seeming game that, through interacting with it, you realize is actually quite intuitive and charming. It’s unlike anything I’ve played in a long time because it trusts you to figure out its appeal. It’s a game for smart people, not just one constructed by a smart person. That’s a crucial difference.