This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Daniel Benmergui usually codes by night in the cafes of Buenos Aires, the Latin American city that was also the birthplace and residence of Jorge Luis Borges, arguably Argentina’s greatest literary figure. Like Borges, Benmergui is a storyteller. Ostensibly, the similarities end there. Benmergui is 36, athletic, and plays the darbouka. In our memories, Borges is elderly, blind, outré. He was a writer of short fiction; Benmergui programs short games. When I ask Benmergui if he would have been a writer in a past life before computers, he types (we are typing because the connection to Buenos Aires is not good), “I would have probably been a poet. I’m not sure I could fit into Borges’ shoes.”

Indeed, those are big, clomping, probably uncomfortable shoes. In another interview Benmergui said he was influenced by the postmodernism of Italo Calvino, not Borges. But while the two Argentines differ in style, artistic medium, and celebrity, there is a big similarity in their work: they both explore story and plot structure through an algorithmic process of calculations and rules. Borges folded mathematical concepts into his most beloved prose. For instance, The Garden of Forking Paths was a valiant stab at shoehorning non-linearity into a forward-reading piece of text. In The Book of Sand, he wrote of a book whose pages were infinitely thin and unending.

Ironically, Storyteller is becoming Benmergui’s book with pages that are infinitely thin. When he originally conceived the idea in 2008, it was a simple fairytale told through a series of moving parts that created various stories. Since then, the project has obsessed and haunted him for six years over several false starts and drastic rewrites. In its current incarnation, you place different narrative pieces—quarreling lovers and daggers and suicide notes—into various cells of a comic strip. Whether the characters love, hate, kill, or curse one another changes depending on how the pieces are arranged. But that could very easily be modified. “What if I gave you a strip and you had to decide what facial expressions the characters had for the story to make sense?” he asks. “Storyteller is not like that, but it could be!”

The final destination is still somewhat in flux. “For me, every game is a long journey through an unexplored landscape of virgin mechanics,” Benmergui says, and Storyteller is a paradigm example. Despite winning the prestigious Nuovo Award at the Independent Game Festival in 2012, the game is currently on hiatus in an unfinished state. At the beginning of the year, Benmergui grew so frustrated with it that he shelved it and began working on a side project for a break. “It’s a good game, with good ideas in it,” he says. “It’s just that figuring out the best way to go about it is like groping in the dark.”

Part of the difficulty is that Storyteller is fundamentally different from other narrative-rich games, so there is no roadmap. Even fascinating titles that use systems to generate sophisticated stories, like Dwarf Fortress and Crusader Kings 2, rely on weighted chance, like you’re sitting at the poker table being dealt your fate. But Storyteller is more experimental than that. Its narrative structure can be radically reshaped in any direction with a few clicks of your mouse. “I always compare game-making to being both a musician and a luthier,” Benmergui says. “You are supposed to give a great concert on an instrument you invented, so you have to figure out how to make good music with a mutating instrument.”

With that in mind, it’s understandable why he is gearing up for yet another Storyteller reboot. It turns out that dynamic storytelling is infinitely more complicated than authoring a book. It’s easy to become overwhelmed by the sheer number of possibilities. A simple story with a few interactions quickly multiplies. For instance, in Storyteller, a murder could be committed by a knight or a villain, with a knife or poisoning, out of jealousy or hate, with or without witnesses, et cetera, all of which Benmergui has to take into account. When you combine the expressiveness of literature with the free will and player agency of games, things can quickly get out hand.

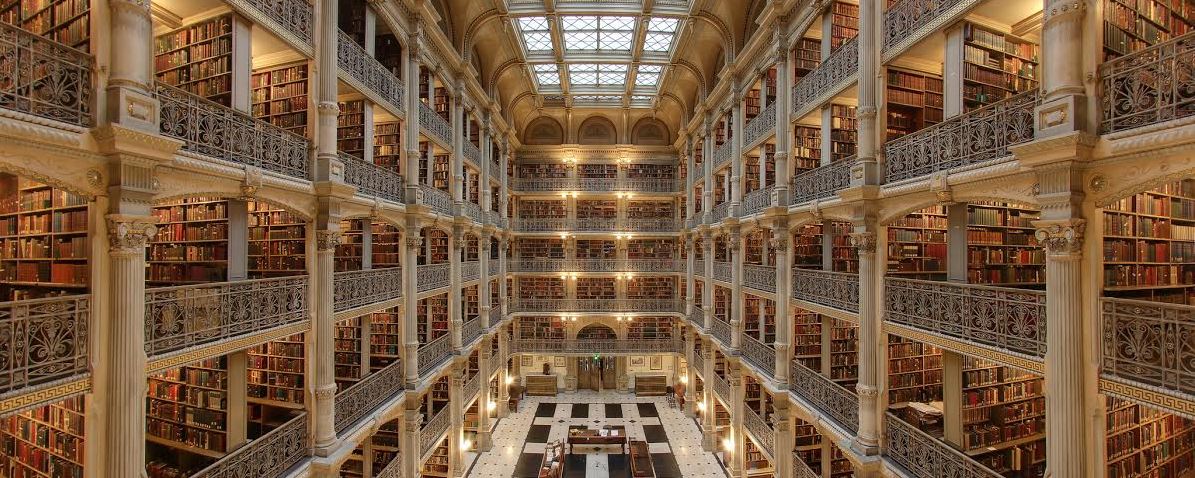

In a way, his dilemma reminds me of Borges’ “The Library of Babel.” In that story, the old librarian has spent his life rifling through a massive library with books which contain every possible arrangement of letters imaginable. Nearly all of the books are nonsensical, but the narrator is driven by the belief that there is one perfect index somewhere among the shelves. It’s a modern parable that illustrates that the concept of infinity is perhaps horrific. The more possibilities there are, the less likely it is we will ever stumble upon the right one. Not exactly a ringing endorsement for the malleability of games.

But Benmergui doesn’t believe that there’s a danger his pursuit will lead to a perpetual spinning of wheels. He prefers to listen to what games have to say and “allows them to make their own choices,” letting them guide him towards whatever mysterious, playful storytelling forms the code has buried inside, rather than imposing his authorial will. “Seriously, if I magically had in my mind all the levels for Storyteller, I could implement them in a week,” he says.