When copper oxidizes, it gives us very calming bluish-green called verdigris. This patina is often so thick that the copper beneath is protected from corroding any further. The pigment was used hundreds of years ago in paints; it is also poisonous. The Statue of Liberty was once a bright, flawless copper.

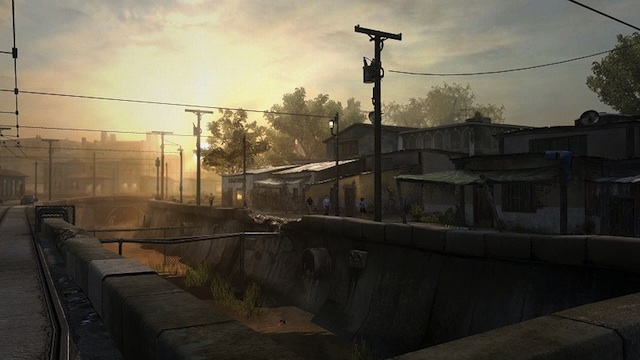

Verdigris is the word I thought of most through Infamous 2, along with corrosion. As Cole McGrath, a parkour world champion with electrokinetic powers, I channel electricity; I course on its force across the open world of New Marais. The city is a model of New Orleans—a former industrial port giant in a complete, unapologetic state of decay. I am forced to engage with the meaning of decay in a city we all know, today, is suffering from near-criminal neglect.

The rooftops are my first play space. Up here, deep cobalt tiles have turned strange, fluorescent colors from mold and wear and wet. Moss edges yellow flowers of grime. I see sights I had never imagined before in 28 years: that the water pipes on roofs are not metal, but an astonishing length of oxidized blue, that a tin roof layered over years looks like a patchwork history of the stages of rust.

As I clamber down from the roofs, I become intimate with the textures of concrete, stucco, wood, brick, iron, and tin. I leap to a lamppost, and then tether myself to a tram line and catapult around New Marais. I grind heavily along wires, along streetcar lines, up wired pipes. I see the veins and guts of buildings as they blow apart in combat: steel girders, drainage pipes, all running down to the thick brick piers on unsteady swamp land. I know the courses of water, energy, gas, and oil, the magnificent understructure above which the city hums.

But first, before the damage—the beautiful facades. New Marais is a testament to New Orleans’ dizzying amalgam of architectural styles, including French, Spanish, Creole, Caribbean, and African, along with famous Greek Revival buildings built during the 1830s.

It is all here in New Marais, in its elaborate wrought-iron arches and balconies, in ornate cornices and filigreed latticework, in the side-gabled roofs. I skip across shotgun houses and verandas, and stone tombs in St. Charles, an old European-style cemetery. I glide across Esplanade homes and struggle to run around vast mansions. I walk through carriageways and back quarters once meant for slaves. I spider across the windows of bars and casinos, with colorful names like The New Moon Hotel, the Yes We Can Can! Cabaret, the Drunken Uncle. I slow my roll, out of curiosity, in the famous red-light district, its bevy of adult theaters (showing at the Hush: Assassin’s Need (Love Too), Little Big Unit). At one point, I stand atop the main cathedral, St. Ignatius, as a honeyed sun sets behind the wide-open palm-tree filled square.

This is New Orleans: gritty, sordid, genteel, heavily textured, brilliantly candy-colored, impossibly rich and dense—architecturally and so, historically. What does New Orleans mean for those of us who do not live there? I think of the New Orleans I have received through Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, even H.P. Lovecraft. Big Daddy and Maggie the Cat. Violence, desire, repression, jealousy, and love at any cost. Idol worship. Institutionalized racism. The macabre and the gothic. Jelly Roll Morton, born in the Seventh Ward. Monstrous awe and passion we wish we inhabited even one day in our lifetimes.

And the architecture of New Orleans is home to this messy romantic fantasy of 19th and early 20th-century decay. It gives us a constant, undeniable sensation of a lost vibrant world. Even as New Marais is still vital, human, immense, it is falling to pieces. In back allies, alcoholics lean into their own sick. The peeling skins of paint, their jagged lines reveal two-century-old brick. The storefront dancing rooms in Sin Central are empty; you press your nose against glass to see little stools squatting, embarrassed, under hot pink lights.

Cole’s missions as New Marais’ emergent hero, saving residents from a purity obsessed militia leader, force me to descend into Flood Town. Life is found here in scattered pockets: a lone man plays a harmonica on a roof. Fires burn in trashcans. Stricken people muck about, knee-deep in the water, sifting through trash. I traverse shaky, tippling pylons.

On one of the first signs before the entry to the slums, we read: Bubba’s Market: Po Boys * Honey Orders * Check Cashing * Beer. This hit me with reality. Check Cashing isn’t a charming local touch of color. Predatory lending and local systems of debt are what take the place of mainstream business investment in this part of town. Yes, the residents are mostly black.

Entrenched socioeconomic disparity and concentrated intergenerational poverty: these are not sexy topics. But I would like to see them more in games. I like that in an intensely fun game, I am, at one point, hanging from the side of a Lot to Loot Lottery shack, mulling how decades of urban planning blind many of us from seeing the potential Flood Towns in our own cities.

This is all to say that New Orleans is as vital a space for possibility, hope, and creativity in our cultural imagination as it is a visceral, present reminder of our civic failures.

I spend most of my New Marais off-time in the wharves, ports, warehouses, shipyards, gas works, and steel mills. Though no employees are around, I can climb onto the massive hammers of the Gas Works, which continue to rotate, lever, and drop with mesmerizing precision.

New Orleans, I remember, is as much made of its industrial and manufacturing heart as by its gin- and bourbon-soaked streets. This was the ultimate American port, made by shipping copper, oil, gas steel, cement, petroleum, carbon steel, rubber, and coffee. The Port of New Orleans still ships just under a billion tons of chemicals, iron, food, and coal.

I clamber to the top of the empty headquarters of I.B.A.U. Industrial Steel, one of many company names seen around New Marais, along with J & I Merger Industries, GWP, and HMD International. The white steel letters S, R, I, and L of INDUSTRIAL STEEL are all bleeding rust. I kneel, ensconced within this old sign, and look out over the smokestacks, the fat snake pipes of the Works, the dockside cranes, and the ships poised for travel. Yes, everything rusts. Everything corrodes. But, if there is to be hope anywhere in New Marais, it is here. The copper and steel and cement we have seen so easily damaged through the course of the game had to come from somewhere. Men had to toil to bring these materials in. And if a city can be built once, it can be built again.