Warning that this review contains discussions of sexual violence featured in the game.

The Detail’s first episode ends on a hell of a cliffhanger. I’ve just returned home after a night that’s involved multiple murders and gang activity, the latter of which involved me walking in on a man getting his face dipped into a deep-fryer. Somehow, that last incident maybe isn’t even the most stomach-turning event I’ve run into: candidates for that award also include rushing into the apartment of a known child-molester while a scream pierces the sky, or, under legally gray pretenses, entering the house of a gang associate only to find a possibly underage girl passed out face down on a couch, her pink underwear flanked by marks of abuse. In the kitchen, a pile of Polaroids on the table reveals more underage girls. A dead rat decays in the middle of the floor.

The only bright spot in all of this, I guess, is that it didn’t happen to the same character. Which is also where The Detail’s first episode draws its strength: ramifications of events happen to other people, but it’s always on our watch. So many videogames are built on the easy idea of shirking responsibilities. As hero protagonists, we intersect with thousands of other characters, irrevocably alter their lives or worlds, and then move on, scarcely—if ever—returning to see what mayhem we may have caused in the life of a digital other. The Detail doesn’t want you to escape; it wants you to deal with the fact that this is a fucked-up world full of gross protagonists and grosser crimes, each of them with their own rippling effects on others and the world at large.

And so when I—this time as a police informant goaded back into a life of crime—stepped out of the elevator onto the floor where my apartment stood, my stomach dropped, because I knew it wasn’t his fault, but it was still my fault. Earlier, as a police detective, I had done the goading, forced him to return to a life of crime that he had given up for a wife and a kid. The good path. And yet, at the end of the hall, there it was: the door to his normal, beautiful existence.

Ajar.

The game cites two clear influences: one is The Wire. It’s maybe an irresponsible citation, as this first episode is devoid of any discussions or investigations into calcified corruption or entrenched racial politics, those massive, foreboding tombstones of humanity that forever loom over the people trying to live their lives as they are born into this thresher of a system. But I know what they mean: The Detail is about hard things, and it delivers in spades, is a rollercoaster that forces the player to engage in a narrative full of disgusting, wriggling problems that breed in the world’s subconscious: gang territories, human trafficking, molestation.

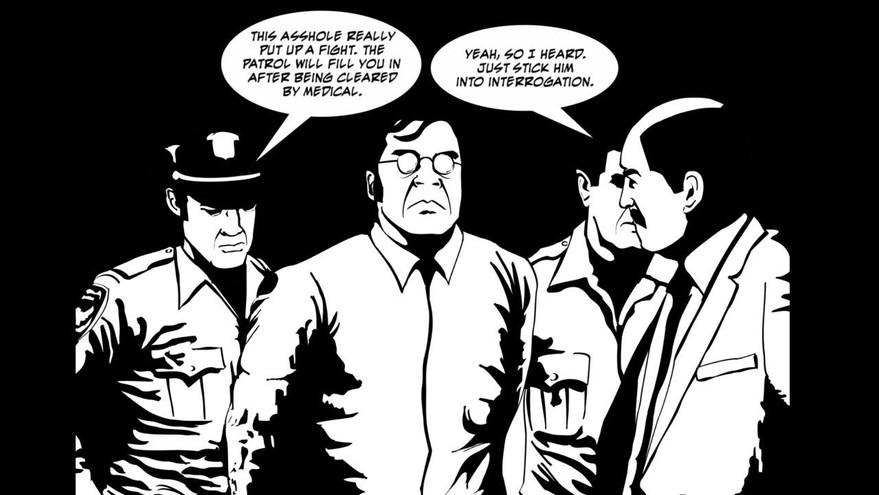

While these moments are successful, they’re also mixed in with scenes of sensational violence, such as the face in the fryer, or a shootout at the top of a hotel that’s not so much a gritty portrayal of American gangs as it is an homage to gangster/mafia cinema. As such, when I (grizzled police detective) am trawling outside of a gang-member’s house to find some way to get him to let me in, I don’t think of The Wire’s Herc and Carver ,sidestepping the law in an example of the trickle-down miscarriages of justice that bleeds out of a corrupt system. I think of a nameless crime-drama version of Good Cop/Bad Cop, which the player was already partial to in an interrogation sequence.

Let it be said that the interrogation only goes down that way if you so choose. The other big influence is Telltale’s The Walking Dead, in that The Detail is a narrative point-and-click adventure—emphasis on the narrative—with choices given to the player in how they can advance the plot (famously: Clementine will remember this). Important dialogue is the stuff of branching paths, and here, of course, were the options to rough ‘em up, attempt to bargain, and so on.

While I praise the game’s subtle insistence on certain choices (violence kept appearing even as other options faded away), what remains to be seen is whether or not these choices will actually make a difference. Going back and choosing the other path, I was often disappointed to find that only the smallest details were different; the molester gets off easy no matter what, be it due to a bargain or police brutality. When I had to surreptitiously alert the police to a gang meeting, it didn’t matter if I stole a drunk’s cellphone or sneaked into an office to use the house phone. And, at the door of the molester, as a different pair of police, I had the choice to kick the door down or pick the lock. While one alerted the perpetrator to my presence, both resulted in a scuffle that led to an arrest. (Laughably, the latter option results in a mini-game, which is nothing new, but in the context of the dark subject matter, it only serves to highlight the frivolity of this medium we know and love: align the moving arrow with the targets while a child is abused.)

In a game about big-picture, important ideas of societal problems, a lot of the choices feel not-so-important, and this isn’t so much admonition as it is a warning: the following planned episodes must come to term with the choices set forward in the first, must tackle those ripples in a genuine, authentic manner or else we’re basically playing a comic book and imagining different actions between panels. I don’t have a problem with that; I’d be more than happy to follow through the starkly Miller-esque illustrations of the comic-like world and feel the predicated consequences develop across different lives. I do, however, have a problem with the game pretending that my choices in those sequences might matter, only to reveal that I wasn’t so much a player as I was a casual observer, chained to the same outcome no matter what. If this powerlessness is metaphor for the ingrained despair of the justice system, well, great—but that, like a lot of what makes up The Detail’s potential, remains to be seen. Luckily, there’s a lot of room left for it to unfold.