“We often obsess over games as power fantasies, touting ‘possibility spaces’ that equate choice to fun,” says Ansh Patel. He’ currently mid-way through authoring a six-part videogame series that seeks to deconstruct our notions about player agency. “There are so few examples of games that constrain the player’s expressiveness in order to allow them to experience something specific.”

So far, each game released in Agency? (three more are slated by April 19th) forces the player into an uncomfortably tight corner: whether mentally, physically, or both. By removing fundamental assumptions about the relationship between player and game world (like goals and feedback-loops) Agency? casts doubt over designers’ dogmatic approach to player choice.

Agency? casts doubt over designers’ dogmatic approach to player choice.

Focusing solely on one type of player interaction, Ansh says, will tend to produce one type of experience—typically a power fantasy. “But the games in Agency? are about experiences where people don’t necessarily have a lot of choice: whether they’re living under constant surveillance, torn between applauding for an encore and simply giving up, or battling depression.”

Ansh’s short-form games subvert everything you’ve probably come to expect from being a player in a videogame. While usually every player-input produces some sort of visible output, Security Guard Simulator offers only dummy objects that barely react to your presence or interaction. A phone rings, a cellphone lights up with messages, and your computer screen glows with information about your new surveillance job. But while you can touch, pick up, and look at each of them, the biggest effect you’ll have is getting the phone to stop ringing—momentarily, before it starts up again. Each time you pick up, there’s nothing but an empty sort of sound on the other side.

“The more you poke and try doing things, the more you realize how the inaction and inability to carry out tasks leaves little purpose to these people’s lives.” There’s also a subtle Big Brother-esque undertone to the whole world, with lists of strict conduct rules plastered across the office, along with a mouse-cursor that resembles the watchful eye of a surveillance state. Ansh says that the inability to actually do anything “over time transforms into paranoia in the player’s mind, as they think about how their inaction will be interpreted by the surveillance system.”

By insinuating goals and the ability to take action while never actually allowing the player to control much of anything, Security Guard Simulator “implies this idea of a totalitarian system providing a hollow illusion of a purpose,” according to Ansh. Which, incidentally, sounds like a pretty good description of some of the games I’ve played in the past.

“this idea of a totalitarian system providing a hollow illusion of a purpose.”

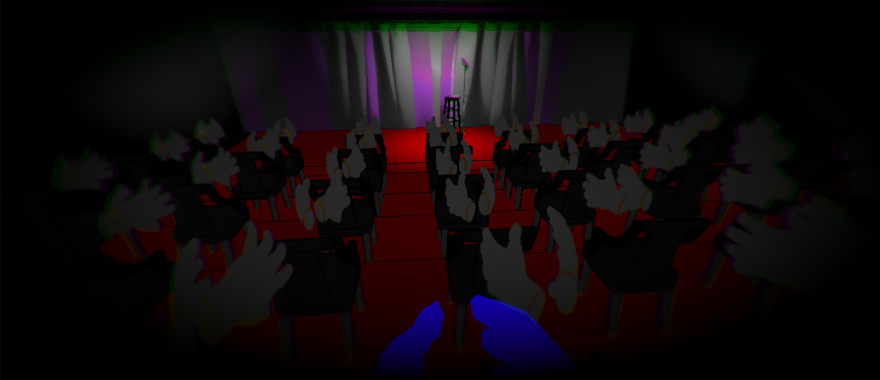

The second installment in the series, Encore, tackles a different kind of expectation, by zooming in on the moment after a concert when the audience hopes to coax the performers back on stage with pure enthusiasm. Stage hands run across the stage in Encore’s abstracted world, their ephemeral shapes running causing the audience to hold their breath as they wonder whether the instruments are being prepared for an encore, or just being packed up.

You’re a pair of hands—just one among a million adoring limbs trying to make enough sound to bring back the music you crave. Ansh says the disembodiment of the hands shows how “when we’re all collectively performing the same set of actions, it’s almost as if the rest of our bodies cease to matter.” We become the applause, our only form of interaction with the world a noisy clap of fanaticism.

What Ansh found so intriguing about a videogame tackling the experience of an encore is how the ambiguity of the moment forces players to question their own efficacy. “We’re not sure if cheering harder will convince the performer to come out again or not. We’re clapping with an uncertainty, not knowing what the outcome will be. In a way, it reveals the illusion of control—of being able to influence the performer’s choice.”

The restrictive controls remind you of the few choices you have in this kind of situation. You can either a) keep hoping and clapping, or b) give up and slowly exit. Eventually, you give up, because the performers won’t ever come back out. No amount of input from the audience can change the pre-determined outcome, just like the pre-determined system of a videogame that can’t truly account for player choice.

like the pre-determined system of a videogame that can’t truly account for player choice.

Moving on to Perfect World, it captures the dismantling of a game system that does try to truly account for the player’s free will. Coinciding with a narrative on battling depression, the sense of alienation from the disease coincides with the alienation of being the only human outlier in a mechanical system. “That is what depression feels like to me sometimes,” Ansh says. “Like trying to process your own thoughts, but they seem very alien and unclear to you.”

Perfect World demonstrates the despair of realizing we only think we have control over the world, while it spins on in spite of us. Though there are five different types of endings, your choices in this Twine glitch game do not change the eventual outcome (which warrants a trigger warning, by the way). The lack of agency in Perfect World speaks to how, “the notion of control stands on an even shakier ground when you’re depressed. The illusion taunts you in a way, making you think you can just will yourself to get up—but everything you try to do or think only makes it worse anyway.”

The ultimate success of the first three games in Agency? is how it puts theory to practice. As a games critic himself, Ansh Patel has written extensively on games that toy with player agency. Agency? demonstrates just how evocative games can be when we rethink the underlying assumptions that too often drive design. Though Ansh also thinks that “a lot of it has to do with us trying to reduce the core essence of our idea to fit the restrictive boxes of these tools and engines we use to make these games.”

The lack of goals and efficacy in Agency? raise important questions about putting player choice on a pedestal. However, Ansh doesn’t doubt the value of games as a tool for experience. Though choices may only be an illusion in games, the players decisions aren’t meaningless whatsoever. “The fact that the player made those choices without knowing how it would affect the outcome only speaks to the importance of experience over agency in games.”

You can play all the games out so far and watch out for future releases here.