“We want to focus on making a lean, well-crafted game,” says Giant Enemy Crab’s Alex Baard, “and the trouble with all these ancillary things in the modern FPS is that they inevitably take focus away from other designs. It’s far cooler to build all this tension by acting out the lock and load montage, no?”

Giant Enemy Crab’s Due Process is a team-based multiplayer shooter. One team has to breach and clear a building; the other team has to stymie their efforts. Two minutes to plan Madden-style, drawing “plays” on a top-down blueprint. It’s like real-time Frozen Synapse: plan your team’s movements, anticipate your opponents, and then execute. The execution stage of the game can take seconds, depending on your predictive prowess. Breach the wrong door and you’re face-first into a hail of gunfire.

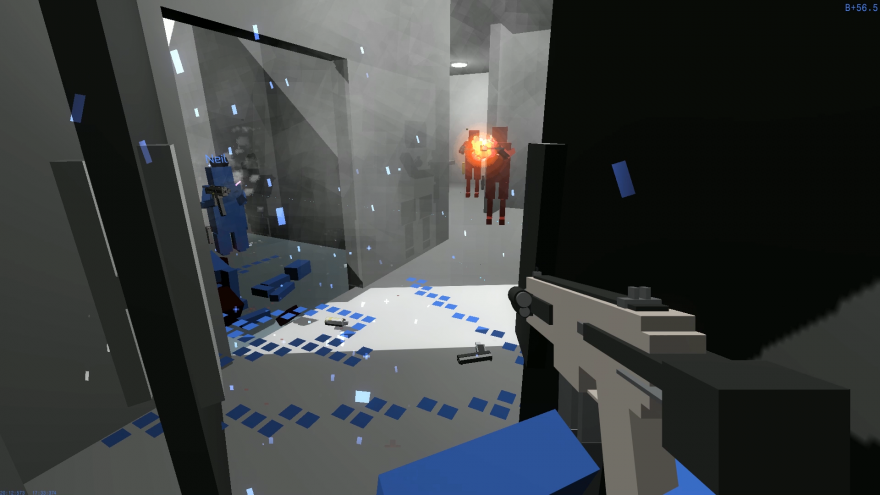

Right now the game is filled with Blendo-type box people, but designer Alex Baard said the aesthetic is in development: “Our cops are one part RoboCop, one part Judge Dredd.”

That’s part of what makes Due Process unique, Baard says. “A subordinate theme in our game is the war on crime and how that may not be such a great idea.” It sounds like a straightforward Rainbow Six/SWAT shooter but exists in a late-’80s/early-’90s action limbo, the era of big-budget heightened reality. Think the massive sets, garish costuming, and squibby violence of They Live, Judge Dredd, Demolition Man, Universal Soldier, Strange Days, and Total Recall. “There’s an ineffable charm to the visuals of that era that we’d love to capture,” Baard says.

To call this a treatise on violence may be a stretch—Baard concedes that “our game is fundamentally about shooting people”—but one thing that characterizes the best action cinema is a light touch with the subtext (e.g. the brisk satire of RoboCop).

For Baard and the rest of Giant Enemy Crab, the focus is indeed on fast-paced action. The planning stages of the game evoke “the heist-movie planning montage,” though this leans more toward the centerpiece gunfight that splits Michael Mann’s Heat in two than the spare meditative calm of Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Cercle Rouge.

Or, to split the difference, Point Break. The team have a firm handle on channeling their deeper concerns through design and letting the game float free in three-minute bubbles of abrupt violence. If they can deliver, there’s no better homage to their heroes than that.