Western depictions of mental illness often tend toward the dramatic. Shows like House often showcase rare disorders or extreme versions of a diagnosis when they mention mental illness at all: the schizophrenic woman who sees fire where there isn’t any, a mute patient who is able to speak after one redeeming event, or the man who had bipolar disorder and kept it secret after opting for an experimental surgery—one that ultimately resulted in malaria. In other cases, the idea of insanity is used as, if not a comedic device, a warning; one simply cannot look into the face of an Eldritch abomination or other horror without losing part of oneself, and many a psychological thriller’s plot revolves around an obsessive lunatic. Mental illness in fiction is often used as a way to strip individuals of their humanity and, in doing so, reflects a cultural fear of what happens when we, too, descend.

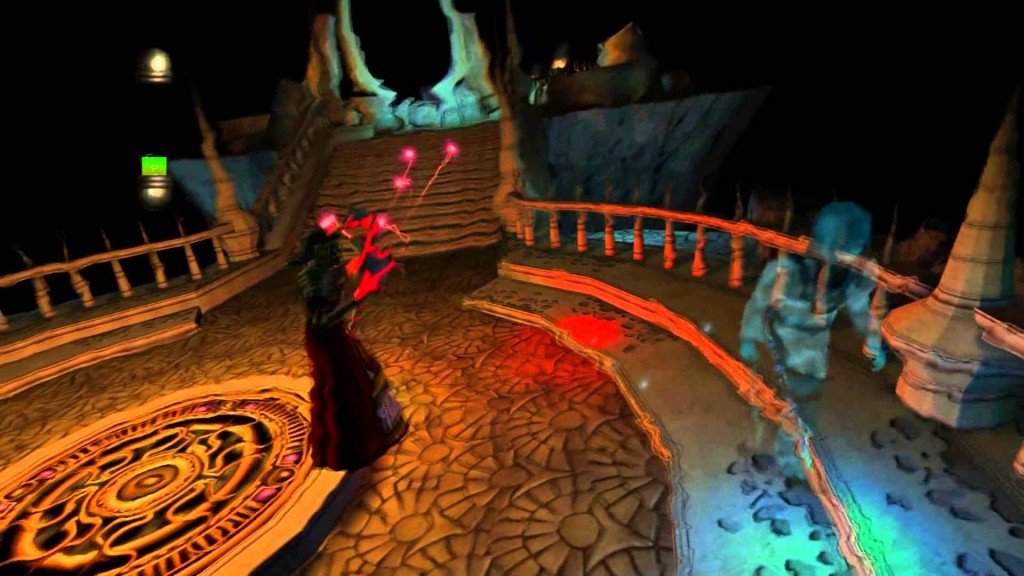

The videogame Eternal Darkness, released in 2002, centralizes this tension. Billed as a “psychological horror action-adventure,” the game’s most notable feature is a sanity meter that glows green on the left-hand side of the screen and depletes whenever the protagonist comes face to face with a monster. Once the meter dips low enough, in-game and fourth-wall-breaking (in)sanity effects begin to take over—the screen tilts, save games “disappear,” the protagonist has auditory or visual hallucinations, and the player’s television appears to mute or go to a blue screen.

While the game may not explicitly categorize the sliding scale of sanity as mentally stable versus mentally ill, the mechanic and effects are consistent with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some studies suggest that up to 40% of combat veterans with PTSD experience psychotic symptoms, and the probability increases the more burdened by PTSD they are. In Eternal Darkness, the godlike character Xel’lotath, whose domain is sanity, is herself depicted as “insane” via a Hollywood-esque version of dissociative identity disorder in which she appears to have multiple versions of herself that are aware of each other and converse.

The horror of Eternal Darkness therefore lies not in the monsters your character must fight, but in the long-term impact of encountering those monsters. As you navigate the game’s settings and your sanity depletes, it attempts to make its point by extending that impact into the player’s technology, wrapping us tightly in the fear caused by the idea that we can no longer trust our own perceptions of the external world. Meanwhile, the icon of insanity is Xel’lotath; sure, she’s powerful, but she’s also an alien, and not exactly someone the player wants to compare themselves to, despite that the inevitably decreasing sanity meter will force those questions. The game firmly aligns itself with the “badness” of mental illness and the value of holding on to your sense of reality in the face of terror.

This one-dimensional approach to mental illness—or, in some senses, simple departure from the “norm” that is often considered sanity—is a persistent theme in media contexts. The 1886 novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, where the titled characters are famously two distinct personalities in one body, is often associated with dissociative identity disorder, and casts Dr. Jekyll’s alter-ego as an evil murderer. The late 19th-century short story The Yellow Wallpaper and Sylvia Plath’s 1963 semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar both comment on the challenges of mental health for women trapped within the context of a patriarchal society, and, in the case of the former, it’s evidenced by the protagonist descending into madness.

In more modern contexts, the tabletop game Arkham Horror dissuades players from taking hits to sanity by sending them to the asylum whenever their meter hits zero. The online game Fallen London institutes a reverse sanity meter—nightmares—which, as it gets higher via otherwise profitable actions, may allow you to understand more terrible things beyond a certain level, but is also a fate widely recognized as not being worth this eventual payout, as you will hit a point where you must wait to return to being functional enough to interact with the game’s world. Finally, Amnesia: The Dark Descent is not unlike Eternal Darkness, in that once your sanity meter falls too low, you are pursued by monsters. While some examples, particularly Lovecraftian media, may assert one is incapable of reaching the same levels of understanding while remaining sane, it is rarely, if ever, regarded as a price one ought to pay, and it’s considered “bad” to lose one’s sanity at all.

And then there’s Psychonauts. Originally released in 2001, Psychonauts is more overtly a game about the mind, mental illness, and other emotional problems. While Eternal Darkness explores the descent into madness and casts insanity as something to be avoided at all costs, Psychonauts takes a more comprehensive view. The protagonist, Raz, runs away from the circus to attend a summer camp for children with psychic abilities. While there, he hopes to hone his abilities such that he can become a “Psychonaut,” and his training largely involves him entering other people’s minds to help them with their mental issues. In some cases the “deeper issues” lie in a past traumatic event or a rough childhood but sectioned off, while in others the entire mental landscape is distorted to represent insanity. In all cases, there are memory vaults, “mental baggage” that takes the form of luggage, and other indications that no one in the game is completely mentally healthy.

At the same time, the game does not equate “mentally healthy” with being neurotypical in a direct fashion, nor does it tie competency to lack of mental illness or past trauma. Not only does pretty much every camper training to become a Psychonaut have traits that code for a mental illness—two happy campers are plotting suicide in attempt to gain more powers, a boy wears a tinfoil hat to avoid making things explode, and another child has extreme hydrophobia—but so do some of the camp instructors. Even characters that don’t have obvious coding, such as Raz, are shown to be wrestling with a deeper issue of one kind or another. For Raz to “fix” an issue obviously associated with a mental illness or help to resolve feelings over a past trauma, the person must be afflicted by it on some level; he does not assume particular eccentricities are a problem in the absence of related distress.

If Eternal Darkness is a game that speaks to “normal” people’s fear of going insane, Psychonauts is one that delves deeper into what being mentally healthy actually means. Eternal Darkness assumes it is impossible to see terrible things without going mad; Psychonauts largely assumes you’ve gone through something terrible, but recognizes the impact of that on your psyche is dependent on how you handle it and how your mental landscape looks otherwise. While it’s possible to restore sanity in Eternal Darkness via a particular finishing move, that it takes a one-dimensional view on it and implies a lack of sanity is less desirable has powerful and negative implications for mentally ill people outside of the game—in essence, it says that the deviation from the normal is itself the problem, and fixing it requires one to return to it. Psychonauts, though arguably poking fun at particular mental illnesses, takes a more positive approach: it says everyone’s mind is its own world, and “getting better” means handling our issues in the ways that make the most sense for us while embracing the rest of our eccentricities.