It’s always funny when creators and/or critics describe a piece of art work as being about, oh you know, just life, time, love, death, and space. They could just say it’s about “everything” to save you time, but don’t (presumably to hear themselves talk.)

Vincent Morisset didn’t describe Way to Go like that, but he should have. Because it really is about life, time, love, death and space—all at the same time. At least, that’s the closest I can come to summarizing it in one sentence.

“I have a really hard time describing this project,” Vincent agrees. “I feel a bit goofy. But it’s interesting because when people play it, they have this smile on their face the whole time, but afterward it takes them a while to distill and process. I think the game just kind of feels like a UFO.”

But Way to Go is like the friendliest, most delightfully surprising UFO I’ve ever encountered.

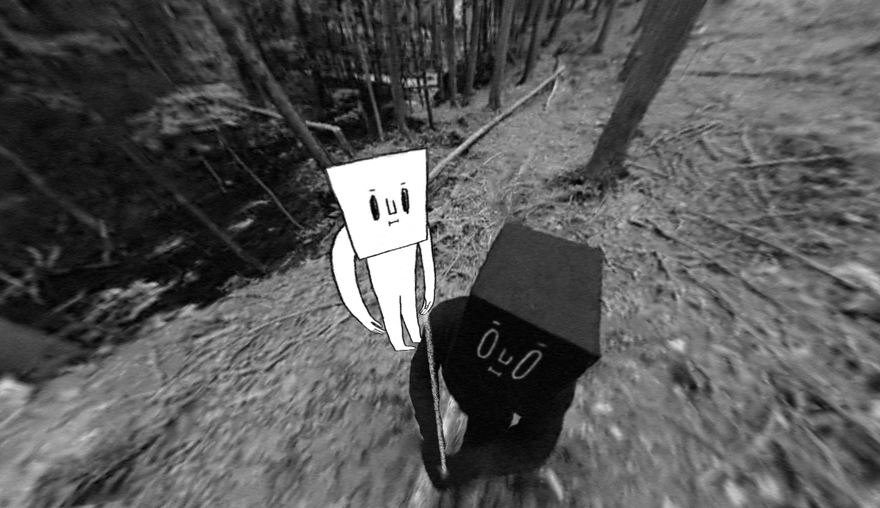

Pointedly, there aren’t any instructions for Way to Go other than: go on. After quickly ensuring that you understand “no one is waiting” and “no one is keeping score,” you begin on a linear path set ahead through the forest. In the gray-scale, oddly realistic world, your cartoonish avatar stands out like a beacon.

Like life, your path is always linear in Way to Go. As you walk, jump, and run across the forest, a stream runs to your right “like a metaphor for the elasticity of time, while you move through a path that only flows in one direction—that you experience at whatever pace you choose.”

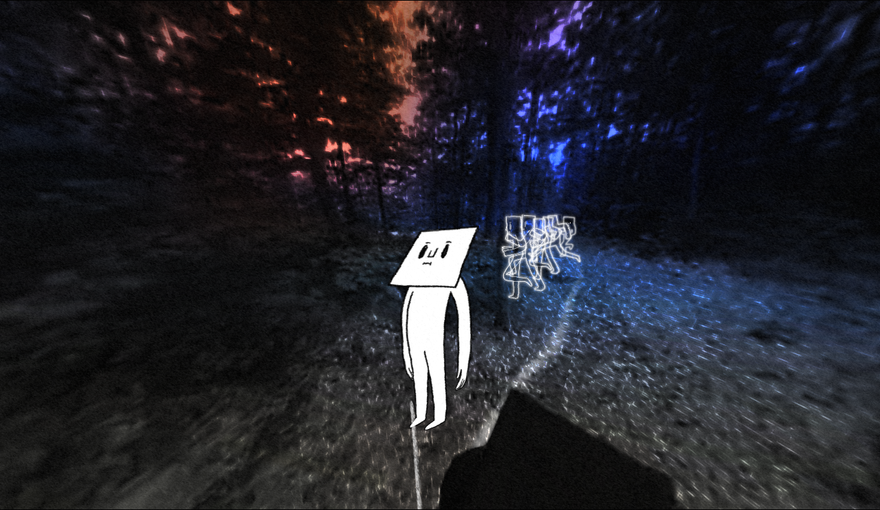

Like life, there are cycles. Periodically, you enter different mirrored realities—which I began to view as a different perspectives or frame of minds instead of separate spaces. Combining 360 panoramic video and hand drawn illustrations, each world carries it’s own texture while maintaining the same sensorial foundation.

In the first world, I took my time to acclimate to the experience of Way to Go, like a child struggling to grasp its first conscious experience of a car ride. In my frantic fumbling, I tripped over a black figure following closely behind me, who I hadn’t noticed until just then. While my immediate response was suspicion (how long had he been there? I thought no one was watching?), I quickly learned my companion was nothing more than a harmless conductor, helping me direct this exploratory symphony.

In real life, the figure is Vincent, wearing all black clothing and an augmented animated cartoon face. When the team shot the film within Montreal’s expansive woods of Mount Royal, he had to stand in the shot like that in order see what he was filming. So, they went with it, establishing black figures (who are all contributors on the project) into the narrative that follow you around in a ghostly game of tag.

Though Vincent Morisset identifies as an interactive filmmaker (director of the Emmy Awarding-winning Arcade Fire collaboration Just a Reflecktor), he says that because he “wanted to explore space and time and control, videogames seemed like the best place to do that.” He used to play games—built a career in something as parallel to the medium as possible—but stopped for reasons he can’t really explain. While he’d recently become enamored with the maturity of the interactive experiences offered in games, he tended too feel “almost anguished while playing things like Skyrim: just left in this giant world, not knowing where to go and what to do first.”

That’s why Way to Go simplified to a mouse/tackpad for looking, two buttons for playing, and an experience ideal for everyone between the ages of 5 – 105 years-old. In the same way that they aimed to “bring the universal or common experience into a digital journey,” the AATOAA team designed the avatar to “be universal in a way, too; he’s cute, but also kind of weird. You project yourself onto him, because he’s like a blank or in-between space.”

In a unique way, the limitations imposed by the medium and technology shaped what Way to Go became. Aside from creating the necessity of a Vincent-shaped tour guide, the use of video also required a linear timeline. When you stop moving to look at the stream or listen to the birds, the film stops too. It’s a distinctive experience, the animated layers keeping the scene alive while the rest of the world hangs in indefinite suspension.

Way to Go is as much a commentary about life and time as it is about imagination and creation. The generative, interactive music score springs from the Euclidean rhythms that organically arise in the sound effects of your motions. The tempo is self-triggered: a soundtrack essentially born from the speed of your curiosity, and harmony with a world already attuned to your every movement.

“The main premise for Way to Go was exploring how we, as human beings, relate to our spaces—how you feel as you discover a new one,” Vincent explains. In his line of work as an interactive filmmaker, Vincent has come to see “human beings as a paradox when it comes to experiences: on one side, we want to be taken by the hand; but on the other, there’s the strong desire for freedom and control.”

Despite how alien an experience like Way to Go may feel to everyone on their respective sides of the “interactive native” spectrum, there’s also a certain familiarity to it. “There’s something reassuring about just taking one path. It’s almost an homage to the games I used to play as a kid, when you went in one direction and followed one path,” Vincent says. Yet while being an homage to those traditional videogames, they also “really wanted to avoid a rewards system that rewarded a specific type of behavior. So instead, if you are a more contemplative player, the game rewards you with examinations of little details in the environment. But, if you just want to run through everything, you make these upbeat rhythms that are also just as satisfying.”

By far my most satisfying moment in Way to Go was when, deep into what I’d call Act III of the experience, you retrace your steps through a de-saturated reconstruction of that original grayscale forest. You know where you’ve been before because, each time you’d clicked the mouse, your outline had left an impression on the environment. “We wanted that moment to be like a pause in the perpetual progression, where you can actually see the way you discovered something,” Vincent explains. “There’s such an emotional reaction to retracing your steps. You re-live the discovery—remember why you jumped so much here, or what made you go crazy with clicking the mouse so many times there.”

At the end of the day, after you’ve lasted the whole length of your defined path, black-clothed angels gather on each side of you. Seemingly, this is the call to a final ascension, where you may survive as the infinite cycle of perceptions (you’ll think I sound less high once you’ve played it.) But, by the time the game tells you the linear narrative is over, you’re already too far into this new, endless existence to get out. Way to Go makes you dread leaving its world, for fear of losing all you’ve helped create inside it, and all that it helped shape inside you.

“We’ve been working on this game on-and-off for three years, and we’re still having a lot of fun re-discovering it each time,” Vincent says. I haven’t had three years yet, but just one journey felt like enough to fill a few lifetimes.

Though you can play Way to Go for free in your browser, I also suggest you keep an ear out for news on tour dates. Though the team hadn’t created Way to Go with Oculus Rift in mind, they’ve ported the game and plan to tour around major cities with it across the world. For more, keep following the collective through AATOAA’s website, as well as Vincent’s personal website.