Steve Gaynor has this black bird tattoo on his forearm I forgot to ask about. Is he a part-time birder? Is it an ink-on-skin shoutout to Keats? An ornithological sign of allegiance to the Pacific Northwest? I dunno. We got caught up talking about Tacoma.

Tacoma is the next game from Fullbright, the team behind Gone Home. In the abstract, Tacoma has a lot of rhymes with its predecessor: Girl arrives to a new space expecting to meet up with some people, but they aren’t there. So, she has to search the environment for clues about where they’ve gone. It’s a little lonely, unsettling by degrees, and she learns something unexpected about others and herself in the process. Like Gone Home, Tacoma charges you with mining an environment for information—picking stuff up, looking at it, figuring out where it came from and what it does. It’s pseudo-archaeological, reading the detritus of Places People Have Been.

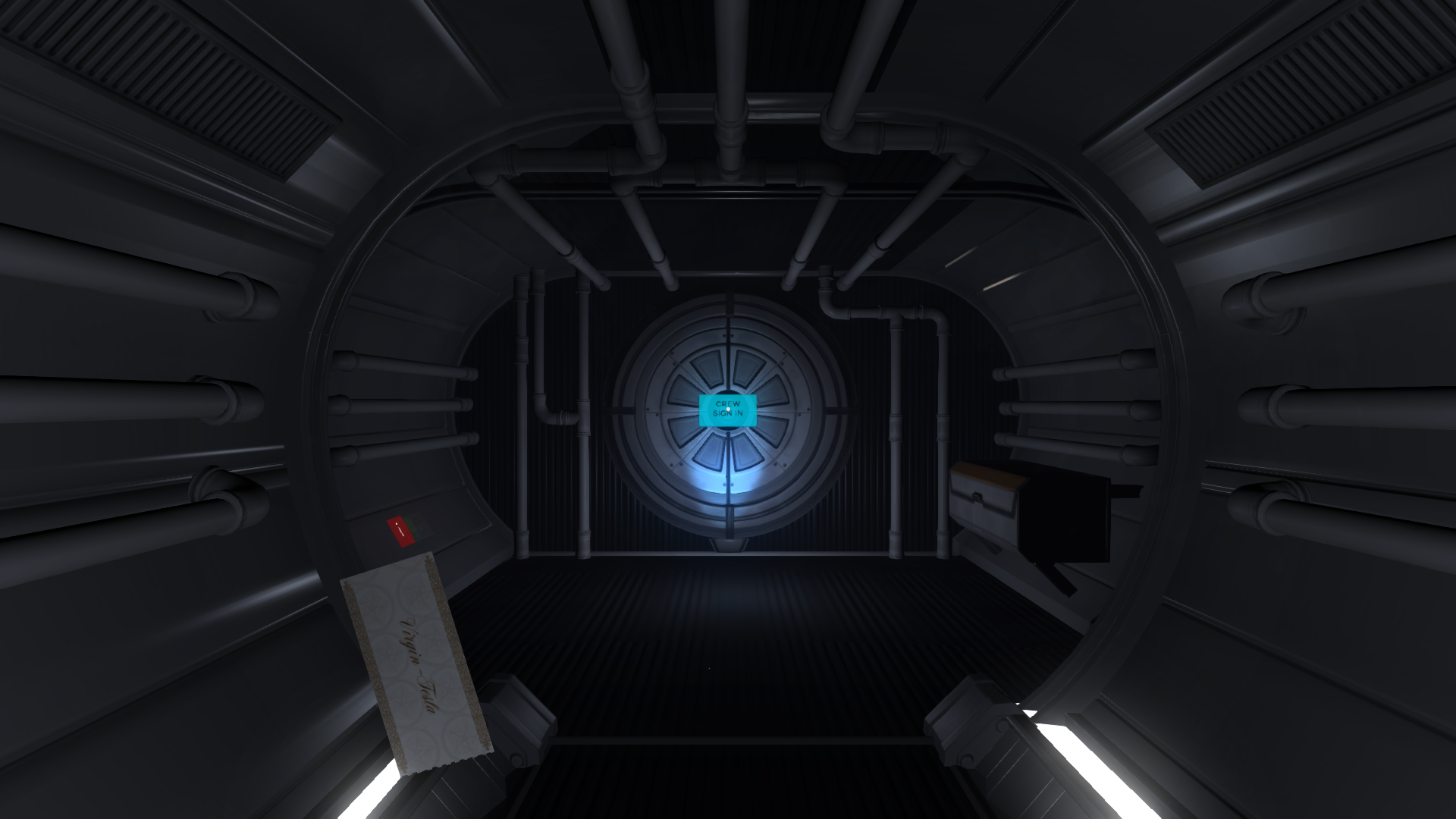

But that’s where the similarities between Fullbright’s games end. Tacoma takes place in 2088 on board a commercial space station, the late 21st century equivalent of yachting out to your private island, maybe. (Really, how do the super-rich vacation in 2015?) Regardless, space station Tacoma—a Virgin-Tesla product in this megacorporate future—hosts to one-percenters en route to the moon. You play a lately hired operations manager for the station arriving on her first day, but when you get to Tacoma you’re greeted not by your blood-and-bone boss, but her walking, talking, very purple hologram. The whole station runs this future-perfect augmented reality surveillance system, where messages are spatially located and your actions are not only being recorded, but can be mimed by holograms in the physical environment. Think of it as an enhanced version of the audio logs peppered throughout contemporary first-person games.

This speculative truth about AR (literally) adds a new dimension to the major mechanical theme of both Gone Home and Tacoma, which Gaynor describes as “mapping information onto a space.” It’s almost mnemonic, a method of loci not designed for Cicero to give stump speeches, but for a post-internet age, which is to say that technologically-predestined-yet-indefinitely-distant moment in the future when the question of what “is” or “is not” “The Internet” will seem quainter than saying “The Google.” In short, Tacoma is both a space and a network. Do we know how to be in an environment like that?

That distance between isolated “thing” and networked “node” collapses further when Amy Ferrier, the player-character, realizes that the only relationship she can have at first is with ODIN, the computer controlling Tacoma, who exists somewhere on the spectrum between Siri and HAL-9000 (or SHODAN, if you prefer). Technologies fail and misbehave even in 2088, but Tacoma wonders about the nature of that failure: Who’s guiding it? A hacker? An AI? And, like our contemporary debate about automated drones, who’s responsible for its actions?

But the future Tacoma posits isn’t just limited to the space station. Tynan Wales, a designer at Fullbright, explains that there are objects in the environment that point back to what’s happening on Earth. “You see a ‘Made in NK’ sticker on something and wonder, ‘So, has manufacturing moved out of China?’” Gaynor explains that a lot of the work of creating a world like this never even makes it into the game. For example, the scientists and employees on board Tacoma must read sci-fi in their downtime. But it’s not enough to say that they’re still reading Arthur C. Clarke. What kind of sci-fi is being written in this particular 2088? The evidence of Fullbright having a conversation about this is a novel on a bedside table, but the ideas implicit in that novel’s cover—say, that the people of 2088 are wondering about what will happen when they start to live on an exoplanet because the strip-mining of Earth is almost done—fill the world.

Of course, as with Gone Home, one of the central risks of telling a story this way—in space rather than over time—is that people will miss things. They have to, even at Tacoma’s walk-through-the-garden clip. But Gaynor and Wales are okay with that. There’s more information in the world that we know how to (or could ever) process, but we manage to tell stories about our lives with imperfect information. Even if it’s set 200,000 miles from our planet, Tacoma might be truer to our world than its AAA Earthling peers who want to make sure the player can’t miss a thing.

Oddly, the question of Steve’s bird tattoo (70% chance it was an owl) is also the question of Tacoma: partial information in context. Gaynor hates it when games try to build their worlds through “Wikipedia article lore,” the long lists of political allegiances in the texts that you find in games like Fallout 3 or Dishonored that seem to be written not to the people of the game world, but directly to the player, papered over with the notion that since they’re in the game world they must be of it, too. Ultimately, Tacoma will give players the chance to interrogate the environment and find the questions to ask. Whether it will give the answers remains to be seen.