Remedy has always come at videogames from a slightly different angle. Quantum Break, coming out this week, appears to encapsulate the developer’s idiosyncrasies. Rote gunplay livened up with time manipulation. And then lashings of bizarre inter-textuality. They did it in the first two Max Payne games, and they did it again in 2010’s Alan Wake. But Max Payne is where it all started, the genesis of ideas the Finnish studio is still working through today.

///

“Outside, the mercury was falling fast. It was colder than the Devil’s heart, raining ice pitchforks as if the Heavens were ready to fall.”

You’ve got to hand it to Max. Even under circumstances of utmost duress he’s still able to turn a phrase like the one above. Hats off: it’s more than I could manage in his position. Max, the titular protagonist of 2001’s Max Payne, is having a shocker. Three years before the events of the game, Max’s wife, and their baby, were murdered. Cut to the present day and Max has been undercover for those interim years trying to halt the distribution of designer drug Valkyr, the same drug his wife and child’s murderers were high on when the killing occurred. And, following an anonymous tip-off, Max has just been framed for the murder of his colleague on the DEA, with the mob and police gunning for him. Max, you see, is having a hard time.

In the first 20 minutes of Max Payne, Remedy has almost played its full hand. There’s the hardboiled Raymond Chandleresque script—awful, yes, but not without charm. There’s the cast of characters that consists entirely of the criminal underworld, bent cops, and drug addicts (prostitutes appear later). There’s New York City itself, coated in enough muck and grime you could scrape it off with a knife. There are the horror elements surrounding the death of Max’s wife and baby, which are truly unsettling, and there are also the references to Norse mythology that surface throughout the game. And then, as a garnish to the dish, there’s the bullet time, a mechanic seemingly beamed in from The Matrix (1999) with nothing to tie it to the world or events of the game. Max Payne, it’s fair to say, is a shitstorm of influences and it absolutely shouldn’t work. But it does, just about.

What’s holding it all together is, primarily, Remedy’s take on New York City—a construction of stylized bleakness, a mirror to the depravity of Max’s personality. The worst snowstorm in the city’s history has hit, meaning the citizens are at home, waiting for it to pass. Max, though, is out on the streets, crunching through the snow. There’s an eerie quietness to these sections where you’re moving from one interior to another, forced to brave the elements, but once Max returns inside it’s back to Remedy’s squalid, debased vision.

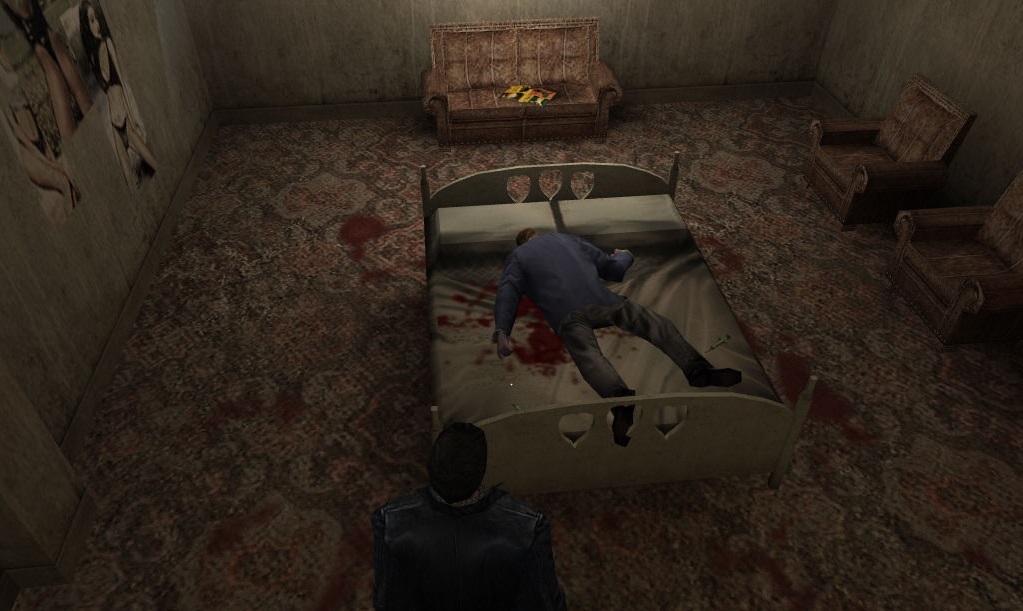

It’s in the first of the game’s three acts where this vision is fully flexed. Max visits a seedy hotel owned by mobster Jack Lupino: the paint is peeling off the wall, yellow cigarette stains color the ceiling, and damp seeps through the walls. It’s brilliantly grotty. Act one climaxes in Ragna Rock, an old theater turned mobster nightclub. The mood is oppressive throughout as satanic imagery gradually reveals itself while Max descends deeper into the club, the darkness offset by the neon lettering. It’s sleazy, sticky, and totally memorable.

And then there are the horror sections; the drug induced nightmares Max is subjected to at various points throughout the story. I remember playing through these when the game was released, either 12 or 13-years-old, and being utterly terrified by them. The screams of Max’s wife, the wailing baby, the contorted perspective, and that blood maze, navigated by following the cries of Max’s dead child. Playing through it now, the mood holds, and compliments the main action of the game. Too often, though, the nightmare sequences descend into frustration as Max is unable to find a way out of his own psyche, or worse, falls to his death after venturing too far from the invisible platform the blood trail is laid upon. You’re reminded, in these instances, that this is a game made 15 years ago—a feeling that the shooting, paradoxically, confirms and confounds in equal measure.

It’s basic, let’s say that. There’s no levelling up in sight, there’s no tweaking of the weapons, there’s no cover system. And there’s no regioning on Max’s perp enemies. Leg shot, head shot, it doesn’t matter; they all count the same. Max is merely given a set of weapons and one additional mechanic, the bullet time, to clear each room of enemies. But in that there’s almost a pureness to the proceedings. It has a sharp focus that lends the game a sense of propulsion as Max careers from one room to the next, addled by the effects of the painkillers. For all the talk of balletic gunplay surrounding the game on its release, the reality of the shooting is messy and twitchy. Max lurches from real time to bullet time, scraping by while sustaining huge damage. But in the instances where it does all go to plan, he’s able to transcend the moment. Those slow seconds afford Max a sense of relief, fleeting clarity in a world where morality and purpose seem absent. They are, tragically, minor victories for a man already beaten.

But, really, Max Payne the shooter is the least remarkable aspect of the game. It’s the conviction with which the world is created and presented that makes the game work, from the daft comic book presentation of the story to the relentless fourth wall breaking nonsense. Like I said, it shouldn’t work, but the sheer exuberance of Remedy to chuck this much stuff at the game and, more remarkably, make it stick, makes Max Payne worth playing today.

It stands apart from so much of the dross that constitutes the shooter landscape since its release back in 2001 and right up to the present day. In those intervening years, publishers rinsed the World War 2 setting for all it was worth, and then did exactly the same thing with titles utilizing contemporary conflicts in the Middle East.

More recently, there seems to have been a collective step away from real-world conflict. This year’s Far Cry: Primal retreated into our prehistory while the latest entries in the Call of Duty series concern themselves with future warfare. Quantum Break appears to sit outside of these developments but its sci-fi premise and glossy, contemporary setting already seems less distinctive than Remedy’s previous games. Max Payne, though, stands for singularity, for imagination, in the face of market trends and demands. Playing the game 15 years on, it’s a refreshing tonic to the increasing homogenization of shooters.