Fall of Magic is the kind of free form storytelling you could do with your friends on the floor just about anywhere. Play some Howard Shore soundtracks in the background, light a few candles, and unroll the scroll. As an engine for creating stories it’s deceptively slight. From the rulebook: “Someone may ask, ‘Is a Raven like the bird?’ or ‘What is a Crab Singer?’ To this we reply: ‘It means what you want it to mean.’”

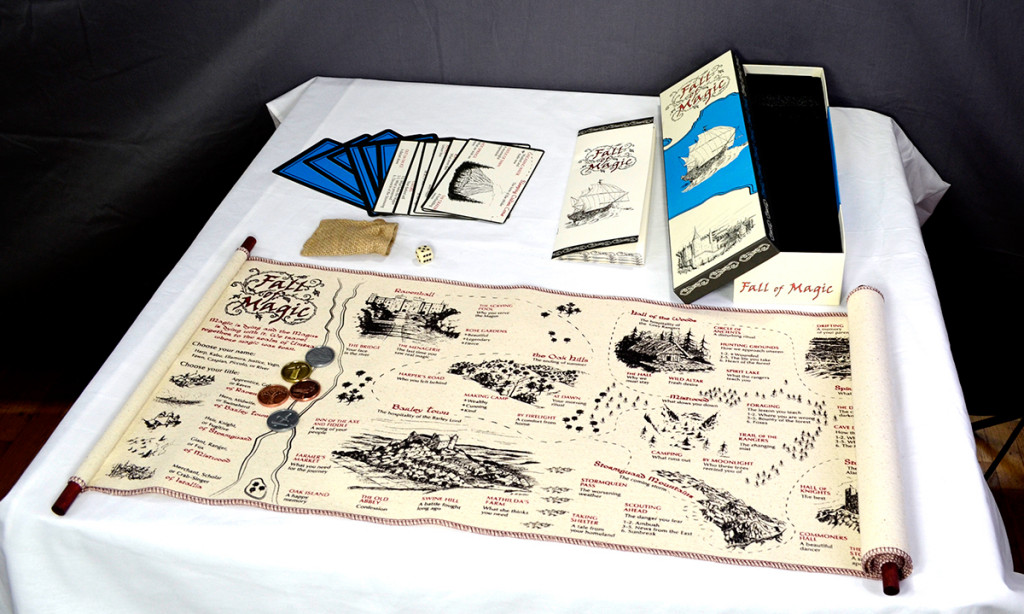

This open-handed approach extends to the rules. A six-sided dice is included but rarely used, and the rest of the game world’s description is confined to brief prompts on the scroll’s scratchy parchment. Certain areas prompt conflict, or drastic character change, but the method and execution is always in the hands of the players. The hazy illustrations and brief prompts function much like stage suggestions in improv; this is a world and a story you are building with your fellow players, and it can be anything you want it to be.

In a sense, Fall of Magic is fundamentally lacking in authorship, which allows the group of players to build (or mercilessly rip off) any kind of fantasy setting or character. When I played with my sister, I shamelessly role-played a reluctantly noble assistant pig keeper from Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles. Another play session was filled with Lord of the Rings references, down to an Edoras-esque deposition of a possessed monarch. However, even as we blatantly stole from better storytellers, we were creating something different, something intentional and personal. In college, my improv troupe attended a workshop by maverick improviser Jet Eveleth (now at ioWest) who coached us to “follow the joy” of each scene and character: “Keep discovering what’s fun about the scene. Otherwise, stop.”

/////

Back in college, my friend Trae came over for what he called “Interactive Fiction.” We drew a map with India ink and textured paper and filled it with Tolkien-esque clichés: a massive wasteland called the “Fields of Hramnor,” shrouded mountains, a place named “The Lighthouse of Amé.” After some preliminary descriptions of the world and culture, Trae sat down with a six-sided die, asked my name and gender, and told me to tell him about my character.

“I’m smart,” I said. Trae rolled the die. A solid three.

“Not really,” he said. “But not all that dumb, either.”

“But I want to be good looking,” I told him. Trae rolled again. One.

“You’re deformed. Like, debilitatingly ugly,” he said.

I threw my pen at him. Several hours later, I’d become embroiled in a quest to impress the local milkmaid in my hometown by killing a dragon on some faraway mountain, even though it was obvious said milkmaid would never love me. My hero ended up heavily scarred but successful, only to return to find his affections spurned again by the maid. After we’d finished for the night, I asked him how he could narrate it in a way that made me feel so deeply for my ugly hero.

“Figure out what the character really wants, and don’t give it to them.”

/////

Fall of Magic’s designer, Ross Cowman, builds games around specific ideas. 2013’s Life on Mars explores the emotional and cultural impact of exploring an alien planet on a ship of interplanetary explorers. Serpent’s Tooth (2012) puts players in a court setting to squabble for power in the wake of a doomed noble’s passing. Fall of Magic, like Cowman’s previous offerings, contains similarly laconic scene prompts and branching story paths, but is very clearly about savoring the journey, taking in each moment, and ultimately about exploring the culture and flavor of another world. It’s a labor of love.

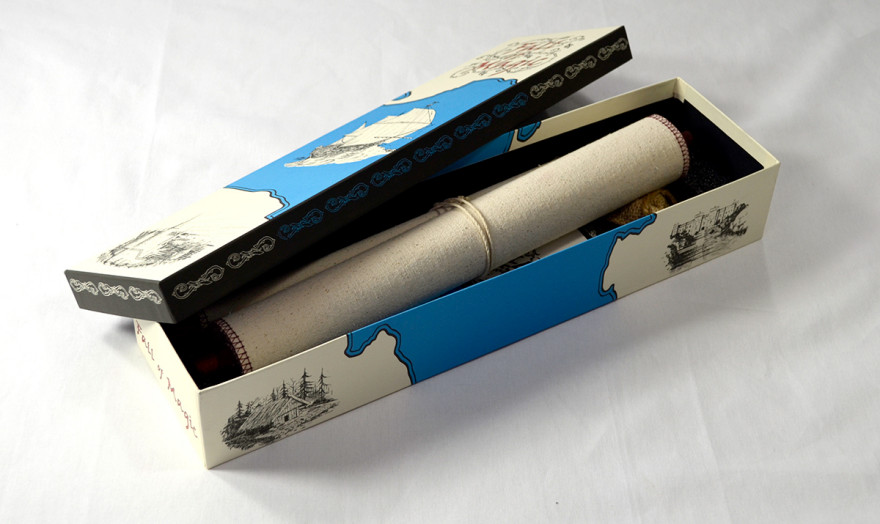

Everything in Fall of Magic revolves around the scroll, and the tactile experience of unfurling the world, thumbing the components. Player avatars are represented by thick metal coins stowed in a small burlap bag, the sides pressed into enigmatic symbols. The edges of the parchment scroll are roughly sewn. Minor but intentional choices like choosing a character’s coin feel significant: Is Ellamura of Ravenhall better represented by a winding river? Or a brimming ocean? Should the Magus’s token be a lit candle, or a burnt wick?

Of course, none of these decisions might be significant. A game of Fall of Magic requires a very specific kind of curiosity and thoughtfulness to build its intended experience. Where a “traditional” RPG like Dungeons & Dragons builds a sense of immersion from rigid mechanics and volumes of detail, Fall of Magic is an RPG for dreamers. The game doesn’t have enough hard edges to entertain the mathematical combat that excites “hardcore” players. Put another way: Dungeons & Dragons is a dungeon-crawl, and Fall of Magic is a stroll in a wild garden.

/////

“If you want to become powerful, I will need something from you,” I intoned, sage-like. It was after college and I was narrating an interactive fiction for my little brother.

“Anything,” he said.

“You will lose your man-shape.”

My brother’s face fell. He had curated his clever, handsome magic student up until now. I’d identified his vanity early in the game and was now using it expertly against him.

“I can get it back, right?”

“Get what back?”

“My, my man-shape.”

“Perhaps,” I nodded.

He huffed and conceded, eventually. I went to our parents’ cupboard and drew out every cooking implement, spice, flavor, and oil I could and dumped them into a single vitriolic brew: whole milk, cumin, pepper, olive oil, sugar, cinnamon, mustard. The smell of it made me sick.

“Drink this,” I suppressed a wicked giggle. “Tis a horrid brew.”

/////

A good session of Fall of Magic unfolds like a shared dream, with everyone in the group contributing piecemeal to the culture, relationship, and plot. If everyone in your group loves Terry Pratchett, the world you build might resemble Discworld; if the party is obsessed with steampunk, the journey could play out like Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky (1989). At every turn, the game encourages imagination, rumination, and the careful (but not critical) thought: follow the joy.

The motivation stands in stark contrast to how I learned to role-play in college. A good game of Fall of Magic entails players getting exactly what they want, and deciding as a group what makes a good story. The game engine enables players who aren’t “storytellers” to tell a good story. When adversity creeps in, it creeps in on our own terms—like when our party’s Crab Singer lost his voice eating a poisoned mushroom in an underground forest, or when we heard a witch-queen had taken control of Castle Stormguard. We introduced these problems with no clear sense of how they would resolve, and were forced to solve them on our own.

Fall of Magic is a strange beast: it lacks mechanical structure, yet is confined to its own rigid narrative. Our group took to flipping tokens to see if certain situations would turn in our favor: full tree means good, bare tree, bad. The parchment map, while beautiful and authentic, constricts every story to the overdone “fantasy quest narrative.” Unless players choose to start in the middle of the journey, the game will always begin in safe tranquil waters, move gently toward conflict, then ebb toward quiet denouement. This binding structure is Fall of Magic’s most pronounced weakness. The game’s rich and slightly tamed garden will be enough for some; for others, Fall of Magic will only spring to life when a group risks the narrative wilds past the edges of the parchment scroll.