With his upcoming game FAR, Swiss designer Don Schmocker says he’s looking to reinterpret the role of vehicles in videogames. It’s not anything outrageous such as making cars edible or turning planes into surfboards (although I’d happily give that game a try too). And it’s certainly not Transformers. In fact, Schmocker avoids deliberately stating what his aim is here.

But, given that the traditional-style racing game has had the majority say in what vehicles in games are good for, we can presume that Schmocker positions his efforts against them. In these racers, the role of the vehicle is to move as fast as you can push it, to have you battle with torque and track records, and to also be the virtual toys of would-be playboys who dream of owning any number of shiny sports cars.

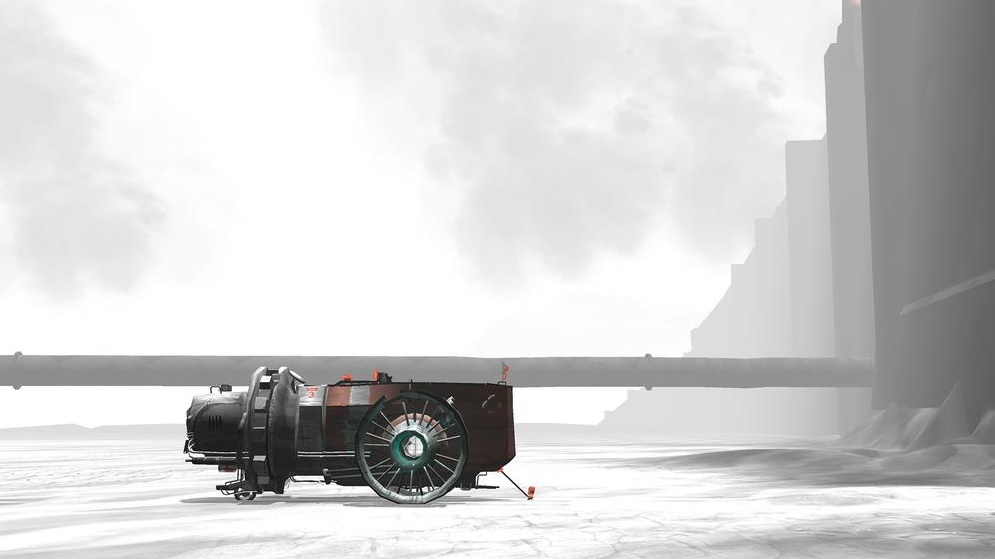

FAR‘s vehicle is a world apart from the luxuries of motorsports. It’s a relatively slow-moving locomotive that looks like it was constructed out of scrap materials that remained after the apocalypse had come and gone. Its shell is a large tin and steel structure that’d be more suited to battering a portcullis than driving across a desolate landscape. It has no windows, billows black smoke from its rear, and runs on huge wheels with broken spokes.

Its interior fares no better than its exterior. As with Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime, you have to leap from compartments spread throughout the vehicle’s entire breadth to operate its many functions—a micro-platformer inside a machine. Just moving this lumbering body forward requires a great effort on your part. Fuel needs to constantly be resupplied with the junk you find outside; the engine will overheat and need dousing in cold water; sometimes you can save fuel by hoisting the sails to catch a passing gust of wind. If you should run out of fuel and have no means to immediately remedy this then you can get out and pull the damn thing. There’s no Game Over and quick restart to help you out here.

You put up with this demanding strain as it’s your only hope against the hostile environment. It’s never stated anywhere in the game but you get a sense that this vehicle is your last hope at surviving. All that is known is that you’re stranded in an endless desert of a dried out sea that is prone to dangerous lightning storms. As you travel, road signs countdown the distance left until you reach the coast as you pass by enormous shipwrecks and wind turbines. The coast is often the destination of survivors in post-apocalyptic fiction, a way to avoid the cities plagued with undead and the like, and this logic seems to have been transferred to FAR.

But this is a game about the journey and not the destination (you don’t even know what you’ll do when you reach the coast). Even with the focus you need to give the vehicle’s interior you can’t help but give equal attention to the sights you pass by. FAR is one of the few games that compares to its concept art. Almost everything is grayscale, which lets drawing techniques such as shading do all the work to illustrate the world instead of the usual superficial fancy. It’s an art style that relies more on the artistry of graphite than it does computer graphics. And this suits the homemade feel of the vehicle and the back-to-basics struggle of its driver.

The black-and-white visuals also mean that color can be used sparingly but to great effect. Here, it’s used to avoid having to use an interface. Instead, our eyes are drawn to the vehicle’s different readouts to help us measure its needs in the same ways its driver would have to. Red indicates interactive objects such as buttons or is used to warn of an overheating engine. Blue is used to point out the fuel meter. The distancing effect that a HUD would have is removed so that we learn to pay attention to changes and react accordingly rather than having to explicitly be told.

It’s this that prepares us to handle the dangers that lie ahead in FAR‘s world, such as a broken bridge, or a low-hanging shipping crate that needs to be moved out the way. The vehicle is a companion (it even talks to you through text readouts on a screen), an educational tool, a machine that suffers wear and tear, and not another object made to dispense thrill at our whim. As with upcoming Eastern European road trip game Hac, FAR is a quiet game that occasionally gets vicious but through the implicit lessons of vehicle maintenance it prepares us for these more testing moments.

A short version of FAR has been finished but it will be getting expanded upon. Find out more on its website.