There can be a fascinating tension in watching old cartoons—we’re talking pre mid-20th century here—it lies somewhere between the familiar and the absolutely unexpected. In early appearances, for example, Daffy Duck showed no signs of the devious but hapless narcissist struggling with his peers for the spotlight that we now know. Instead, Daffy is almost a pure agent of chaos; a mad mallard with a trademark HOO-HOO, HOO-HOO bouncing laugh that accompanies his most successful violations of the laws of physics and common sense. Bugs Bunny might be initially less jarring in terms of personality—he’s a bit more willing to instigate trouble rather than retaliate, perhaps—but his appearance bears little resemblance to the tall, puffy-cheeked gray hare that we’re used to seeing plugging a carrot into the barrel of Elmer Fudd’s shotgun. He’s shorter, more bottom-heavy, and his head is almost a simple tilted oval.

As unfamiliar as these early versions of Warner Bros. characters may be, at least most of their appearances were in color. Tracing Disney characters back to their earliest versions, on the other hand, requires entering an entirely different world. In this world, movement is frequently repetitive and halting, as if every living thing were an automaton, and yet at times the screen is filled with massed activity in ways that color animation rarely tried to match. It is this black-and-white world that Red Little House Studios’s upcoming game Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel seeks to revisit.

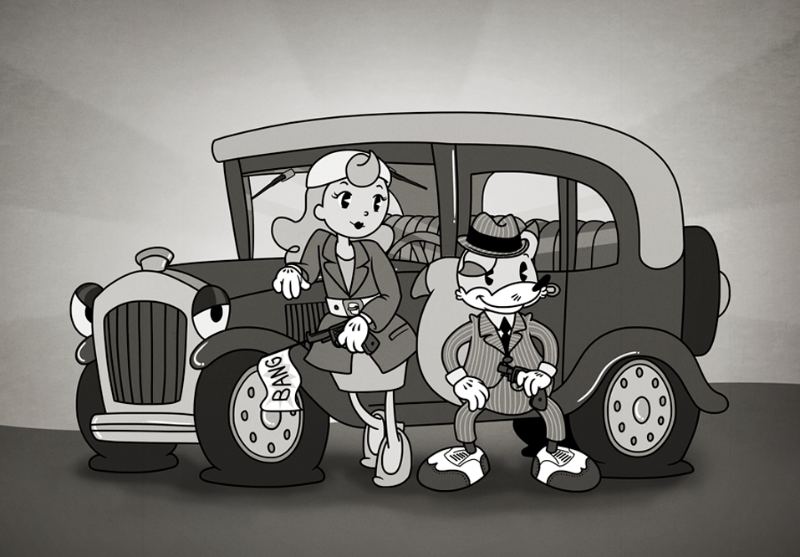

Red Little House Studios, who are based in Valencia, Spain, describe Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel as a graphic adventure/action adventure game set in the 1930s, “the sunset of the black and white era.” When Fleish the Fox is kidnapped by his nemesis, Mr. Mallow, Cherry has to navigate a world of cartoon characters and animated obstacles in order to rescue him. This is, of course, a twist you might not expect to see very often in an old black-and-white cartoon. “The shorts from the 1930s overuse the damsel in distress theme,” says Red Little House’s Iván López, “with Olive Oyl and Minnie being kidnapped and Popeye or Mickey Mouse having to save them. We found that reversing the trope gave us a very interesting story.”

It’s the sort of tribute—sincere, but with a bit of a jab—that one might expect to see in a cartoon where Bugs Bunny finds himself in a nightclub populated with Hollywood caricatures—the 1947 Merrie Melodies Slick Hare, specifically. In other words, it might be just the right mixture of fidelity and irreverence for a medium dependent on establishing its own peculiar laws of reality (see: Cartoon physics), and abandoning those very rules whenever it makes for a good joke. Consider, for example, the rabbit at the center of another tribute to a bygone era of animation, the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. In the second act, Roger, wrongfully accused of the murder of novelty magnate and his wife’s apparent lover, Marvin Acme, finds himself in a secret rotgut room leftover from Prohibition handcuffed to clown college alum and private investigator Eddie Valiant. As Valiant tries to cut through the cuffs with a hacksaw on top of an old, rickety crate, Valiant yells at Roger to hold still, and Roger tries to make himself useful by quietly removing his arm from the handcuffs and using both his hands to steady the crate. Valiant, incredulous, stops sawing.

“Do you mean to tell me you could have taken your hand out of that cuff at any time?” barks Valiant.

Then comes Roger’s telling reply: “No, not at any time. Only when it was funny.”

Like Toontown in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel looks to build its storytelling on a gesture of pulling back the curtain on a showbiz world. Writers Paula Ruiz and David Martínez describe Crazy Hotel as an attempt to explore what happens after the end of a classic cartoon. “Storywise,” they say, “our game is like visiting the backstage from the cartoon shorts.” In contrast to Roger Rabbit’s toon showbiz, what happens “onscreen” to Fleish and Cherry is part of their lives, but their lives don’t end when the camera stops, and onscreen events have offscreen consequences.

If this sounds more like a take on classic cartoons as reality TV rather than the old Hollywood studio system, then it might be the contemporary jab within the period sincerity. “What we want is the game to recall that age,” says illustrator and character designer Raquel Barros, “but without losing our own identity. You can say we are trying to be a 1930s animation studio placed within our time.” And like Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, the most intriguing potential within a project like Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel is the creation of an alternate version of the era from which it takes inspiration.

There is, after all, a stark juxtaposition between the golden age of black-and-white animation and the historical events of the 1930s. In 1928, Disney’s Steamboat Willie was the first cartoon with a fully synchronized on-film soundtrack. In 1929, the crash of the American stock market initiated an international economic depression. In 1930, Betty Boop made her first appearance. The Flowers and the Trees, a Disney Silly Symphony, was the first Technicolor animated cartoon in 1932. In 1933 Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany, declared Führer in 1934. By 1936, Spain was embroiled in civil war, and Germany invaded Poland in 1939. None of this factors directly into Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel, except that for a Spanish developer to create a game as a black-and-white cartoon from the 1930s—a period when a great deal of foreign media was banned—is a striking act of historical reimagination.

It is important to know the way that things were, and it is important to know that they could have been different. And what is a cartoon for if not breaking the rules? Animation, like all media, is and must be a product of its time. But if all media is bound on some level to the world that created it, cartoons can often seem to have their own escape velocity. As Red Little House Studios puts it, even in the 1930s, a toon has easy ways to reach outer space.