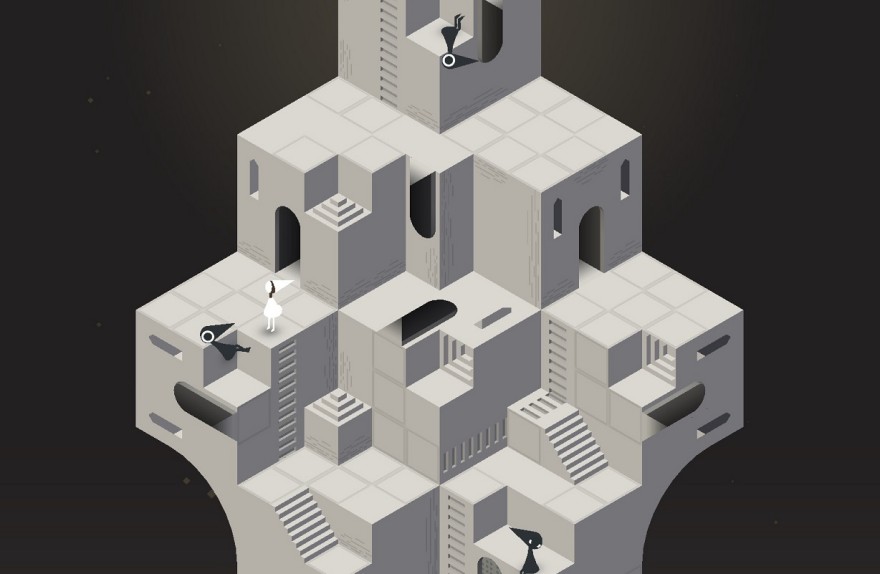

I’m in the Citadel of Despair, an entire realm realized in shades of gray, making it the least visually appetizing chapter of

The trick here is called multistable perception. “It’s in some of Escher’s work, like where you’ve got doors that are inverted next to ones that are the right way up. Or you know when there’s a cube and you can’t really tell whether it’s going in or out? It’s that kind of thing,” Neil McFarland, director at ustwo explains to me.

This is one of the ideas that ustwo didn’t manage to fit into the original chapters of its perception-bending iOS puzzler Monument Valley. The team needed more time to work it out, and when you’re weighing up budget and time limits against releasing a game to hopefully make your money back, you have to side with the more secure option. As far as ustwo was concerned, the ideas that had been dropped were gone for good, never to be revisited; smart concepts that could never be. But that was before Monument Valley became the huge, Apple Award-winning success that it is today.

“It’s been a real vindication of what we’re trying to achieve,” McFarland said. “The reactions we’ve been most pleased with are those that come from people who tell us that they don’t normally play games but they thought it was great. We’ve had some really touching messages from people who have shared experiences with family members. And we really weren’t expecting any of that.”

McFarland only talks about the studio’s success in this way. Money isn’t mentioned once. He tells me that ustwo’s aim with

Releasing a game on mobile in this way isn’t unusual as such, but there is an expectation among players of what they’re getting for their $3.99 purchase. It turned out that Monument Valley wasn’t lengthy and challenging enough to satisfy that expectation for some. In fact, this quickly became its most widespread criticism. Considering this, you may look at the eight new chapters of the Forgotten Shores expansion as ustwo’s attempt to win these people back. It is not.

“People saying it’s not difficult enough, I mean, that’s not the kind of game we want. We don’t want people to get stuck and get frustrated. So we haven’t gone back and thought, ‘Oh maybe we can address those people’s concerns.’ That’s not what we’re about, so we didn’t feel that we had to react to that,” McFarland told me.

Forgotten Shores was created because the newfound security that

The whole idea behind Forgotten Shores is surmised by McFarland when he says “it’s more widening [

Much to ustwo’s despair, this isn’t what was celebrated by many players upon the release of Forgotten Shores, instead it was that the expansion cost $1.99. “Stop being greedy,” writes one 1-star reviewer on Monument Valley‘s App Store page post-Forgotten Shores. There were lots more like this. The united contention of all these 1-star reviews is that the money wasn’t worth the hour-long playthrough, despite many of them also adding that the game is “beautiful” and “an incredible experience.”

There are crow-people that sit atop some of the innie-outie cubes in the Citadel of Despair. When approached by Ida, they let out a horrible squawk that replaces all of my thoughts with a single command: get away. The crow people are loud, senseless, and care only for spreading misery. And they block my way by refusing to move, stubbornly sat in a posture averted to progression. I recall the crow people while reading through those 1-star reviews of

What I can do is guide Ida to one of the grey arched doorways so that she appears out of another one at a completely different angle. Now, with this new approach, when I walk up to the same cube that the crow is sat on it does not open its beak and empty its raucous lungs at me. It cannot see me, and so I pass on by without the unpleasant interaction. Ustwo’s approach to those that have nothing but negativity to throw at their hard work is as mine is to the crow people.

This is a privilege that ustwo has with having such a large audience; there’s more than that angry, loud noise to pay attention to. McFarland tells me that he thinks there’s something special about mobile gaming’s accessibility. He calls consoles a “self-selecting market,” and contrasts this against how most people have smartphones right in their pocket—”it’s much less of a leap for them to experience something on it,” he says. It’s due to this that McFarland reasons there’s a much broader spectrum of people that you can reach by being on mobile.

So while there are those annoying crow-people, you can pass them by, and focus on the positive reactions that people share. McFarland and the team think about how moved they have been by “seeing how far [Monument Valley] gets into people’s lives,” and that’s the doorway they can walk through to escape the noise at any time.

That’s why they can move on now, pleased with what they’ve accomplished, leaving the squawkers to bury themselves in an obdurate irrevelance. “Now we’ve done

Ustwo’s focus now is on finishing its first virtual reality game Land’s End, which will be released on Samsung’s new Gear VR headset some time next year. And then it’s onto something completely new. The team is starting from a completely blank slate, just as they did with Monument Valley, letting their ideas be driven by their aim of moving videogames forward in a more positive, memorable, and inclusive direction.