Alex Hague knows Monikers inside-out. The tabletop game he developed with Justin Vickers gives teams a minute to guess the names written on a selection of its 500 cards. In the first round, anything can be said or done as a hint. In the second, only one word can be spoken. In the third round, only charades are allowed. Monikers is a casual party game, a reality that has occasionally been at odds with Hague’s experience developing it. He knows most of its cards by heart and can list niggling errors that nobody else will ever notice. During Moniker’s final play test night, his guests declared: “We’re just going to get you drunk because otherwise you’re going to be too good at this game.”

“That worked,” Hague confesses.

Monikers’ testing phase is now over. Physical editions have been sent to the backers of Hague’s June 2014 Kickstarter campaign and further copies are available for sale. “There’s such an infrastructure that’s developed over the past two years to allow people to make physical games,” Hague says. As a first-time game developer, he had access to a wealth of advice about Kickstarter, inexpensive manufacturing, and Amazon’s fulfillment services. Monikers has benefitted from this infrastructure and a new wave of interest in lighter tabletop games like Cards Against Humanity and Imploding Kittens.

“There’s very little guidance for that post-backer-fulfillment period,” Hague says. Though tabletop games are receiving increasing levels of interest, there’s no single distribution or discovery mechanism that can be relied upon. Unlike videogames, Hague explains, for tabletop game developers “there’s not the Steam Greenlight or indie dev projects that Microsoft or Sony have.”

Here’s what Hague and more than 2,000 backers currently have: Monikers, in a blue box with characters from the game’s cards drawn on four of its sides. They are, in no particular order: Kim Jong-il, a Furry, Little Mikey, a Russian Nesting Doll, Marie Antoinette, a Luchador, Blacula, and Cocaine Bear. As you lift the box’s lid, another, slightly different drawing of each of these characters comes into view. A bear replaces Blacula’s head. The nesting doll has been un-nested. This cheeky interaction turns each side of Monikers’ box into a two-page flipbook.

Hague says he wanted “to reflect the chaos and spontaneity and weirdness of the game through the unboxing process.” The characters on the side of the box provide an introduction to Monikers’ irreverent sensibility, and do so in a way that 500 cards, laying on their sides, cannot. “People aren’t going to immediately see the ridiculous names on the cards,” Hague explains, “So from pretty early on what I wanted to do was have a representative group of characters from the game on the exterior of the box.”

In its initial iteration, Monikers’ box opened to reveal each character’s skeleton. “Then it became very obvious that…well, it would just be a bunch of people’s skeletons,” Hague recalls. In skeletal form–and skeletal form alone–Kim Jong-Il is barely distinguishable from a furry. “So I went through and created a shortlist of 50 of the cards where there was an interesting before-and-after,” Hague explains, “that we could turn into a joke through this in-person gif effect.”

Monikers’ box is the best way of understanding the game itself and Hague’s motivations in making it. “I really love tabletop games, but it’s really hard to get non-gamer friends interested in them,” Hague explains, “Partially because sometimes they look they were designed inside an Olive Garden.” Monikers is designed to avoid this fate, it is a game you can “take to a bar or to a concert and pull out and have it not be embarrassing,” Hague says.

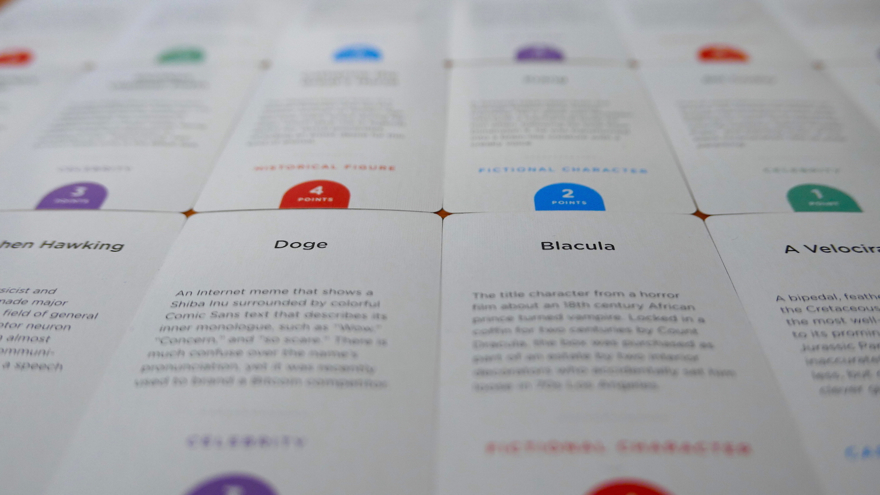

The attention to detail that went into the box extends to the game’s mechanics. Monikers’ is based on and pays homage to the classic party game Celebrity while smoothing out its sticking points. The game’s 500 cards, which were culled from over 3,000 submissions, avoid the pitfalls of relying on your friends’ recommendations. As Hague puts it: “everyone sort of thinks of the same stuff or your annoying grad school friend puts down Henry Louis Gates J and everyone just boos every time it comes up.” Similarly, Monikers’ mechanism for selecting cards–each player picks eight at random and selects five for the central pot–ensures that groups can tailor the deck to their interests. Even the simplest of games can benefit from this level of design.

More than anything, though, the box speaks to Hague’s experience making Monikers. The idea for the box design came out of discussions with friends. Its design gave him the opportunity to work with illustrator Toni Halonen. “I selfishly wanted to work with illustrators that I love,” Hague admits. “I was reaching out to illustrators and…the people who contributed cards, like Andy Baio and Jason Kottke. I assumed none of these people were going to respond because it was this little project that we were working on in the background.” Thus, while the infrastructure for Monikers’ next steps may not fully be in place, Hague has found a different community. “When you develop something like this, you end up meeting a lot of people who you really wanted to meet,” he says. “That’s been really incredible.”

You can get Monikers at their website.