Back in the halcyon days of 1991, a game you played on your television was very, very different than the one you played in your hand. The dominant portable platform, Nintendo’s Game Boy, showed green-scale images that blurred when they moved. Their NES counterparts were relatively crisp, bright, and smooth. But the lesser version was the only way to get a taste of your favorites away from the couch.

Fast-forward twenty years, and Sony’s Playstation Vita can pump out stunners like Uncharted: Golden Abyss; squint and it’s hard to tell the difference between this and its PS3 cousin. Companies like Capcom and Konami, veterans of the pre-Game Boy era, are keen to take advantage of this shrinking gap any chance they can by sharing resources and re-releasing portable games for console.

Less expense and bigger audience equals “good idea!”, yes? Sadly, no. The unfortunate truth is that what makes sense for business also causes an overlap in products where two separate markets, with two separate creative potentials, exist.

– – –

Capcom announced recently they would be porting their 3DS game, Resident Evil: Revelations, to Xbox 360, PS3, Wii U and PC. Revelations was a critical hit, but did not sell as many copies as had been hoped. How best to recoup development costs? Sell the same game on other platforms. It’s a well-worn strategy by now, and for most 3rd-party publishers is the only way to break even on a given title.

But the difference here is that Revelations was built for a portable system. Chapters are shorter, built for pick-up-and-play. Environments and enemies are designed for a small screen, with less reliance on nuance and detail.

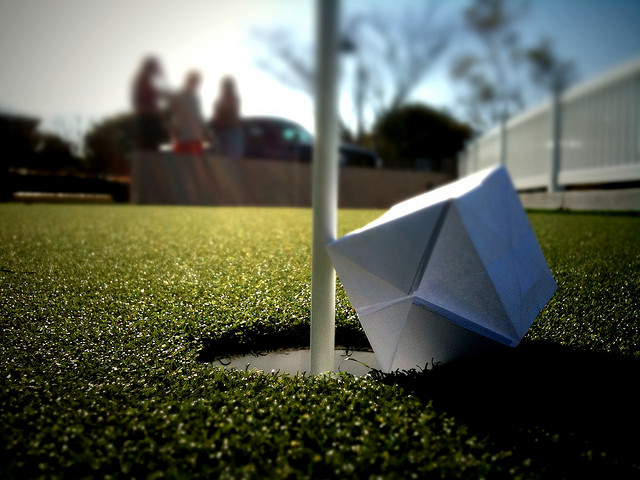

Now blow that experience up for your HDTV and an hour or two on the couch. What makes sense in one situation no longer does in another. It’s like stretching out a lovely 16 x 16 sprite into a full-screen texture: The result is a blocky mess, not because the original concept was flawed, but because the intent no longer matched the execution. A successful handheld game requires a different design philosophy from a console game. When this unwritten rule goes unheeded, bad things happen.

The lackluster sales of Sony’s PS Vita show the consequence of game designers conflating the At-Home and On-the-Go experience. Sony touted the Vita’s power as an asset to be pushed, finally giving us PS3-like games anywhere. And so we get versions of Call of Duty, Resistance, Assassin’s Creed — big games meant for the bigger, belaboured pace of stationary gaming. Public lust for such an option must be low, as Vita sales have been… tepid. Now Capcom hopes the reverse will work, throwing a portable game onto the big screen. The verdict remains out; home versions launch later in March.

A larger concern may be Konami’s recent discussion of their upcoming 3DS game Castlevania: Lords of Shadow – Mirror of Fate. Developers MercurySteam have based the handheld game on 2010’s console reboot, treating Mirror of Fate as a continuation of the series. Which is fine–we’ve seen such extensions of a brand work well before, with Metroid Fusion for Game Boy Advance a notable pseudo-sequel to a console game that fit its platform well. What’s worrisome is the process outlined by Dave Cox, head of Konami UK, while talking with CVG earlier this week. Cox says,

“We created everything in high definition – all the textures, all the levels, high-poly models, everything – and we kind of shrunk it all down into the 3DS. Then we lost bones from characters, you know, we dropped the resolution of the textures and everything to make it fit. At MercurySteam we have an HD version of the game sitting there in a computer somewhere.”

Cox further states that an HD re-release is not out of the question. And while I understand engines and graphics cost money, and publishers hope to wring as much earning potential out of their development costs, I worry that the convergence between portables and console games allows more of these shortcuts to be made. The closer the design plan is between games on separate platforms, the less overall variety exists.

And when these platforms are suited to two entirely separate styles of play, we see less games taking advantage of a system’s unique opportunites. We might get games sooner but we sacrifice much of what makes them special in the first place. Whether on the road or in the living room, everybody loses.