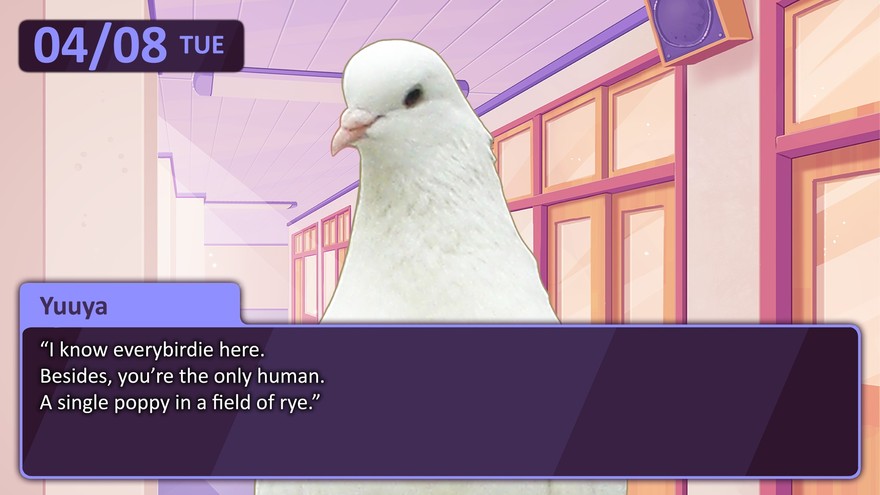

Hatoful Boyfriend is, inarguably, weird. What other word do we have to describe an interspecies dating simulator in which you, a human, navigate the pitfalls of secondary education while simultaneously pursuing a fledgling romance with your choice of bird? What sense of normalcy could ever account for being propositioned by an elegant, sweet-talkin’, sugar-daddy parakeet? What could be more bizarre than you or I, walking arm-in-wing with a fantail pigeon, locked in the triumphant sashay of love?

And yet, the weirdest thing about Hatoful Boyfriend is that it’s not actually that “weird” at all. There might be more weirdness than the average game has, but it’s not exactly different weirdness. The kinds of interactions you have with the two-dozen or so birds you meet at St. PigeoNation Institute, are, ironically, rather human in their scope. Anyone who has graduated high school can attest to the kinds of activities Hatoful Boyfriend asks you partake in. Between looking for a summer job, dealing with social climbers, and managing competing affections, the whole experience actually comes off, however improbably, as fairly mundane.

Hatoful Boyfriend makes it clear that the birds of St. PigeoNation’s Institute are explicitly human in their intelligence. The game offers little backstory, but a little online research reveals that a vaccine intended to inoculate humans from—what else—bird flu had the unintended side effect of giving birds mental capabilities, both intellectually and emotionally, equal to our own. In other words, these birds don’t experience themselves as birds, but something more like humans in a birds’ bodies.

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that the novelty of Hatoful Boyfriend begins to wear off rather quickly. It’s not hard to pinpoint when this happens. At precisely the moment you begin to think of the birds of St. PigeoNation’s not as birds, but as the (human) personalities they parody, the experiential weirdness starts to deflate like an aging balloon and the game becomes the very thing it was intended to parody. Underneath its avian gimmick, Hatoful Boyfriend just another dating simulator.

It didn’t have to be this way, of course. Written differently, Hatoful Boyfriend could have disguised a deeper inquiry into the very nature of love. The game offers little insight into the love we feel, or don’t, for other humans, but even less about what it would be like to love a bird (or to have a bird love you). In videogames, love is often a goal, if not an achievement in the literal sense. But what if a game didn’t simply assume that that such connections were the goal of having relationships with other beings? Indeed, what if the game didn’t assume that such connections were even possible, but instead probed the depths of their possibility?

Under these terms, Hatoful Boyfriend wouldn’t be a game about a world in which we humans can take pigeons as our lovers. Instead, it would be a game that forces us to ask ourselves if and how one might learn to love a being utterly unlike one’s self. Such a game would have less in common with the dating simulators Hatoful Boyfriend ultimately fails to lampoon, and more in common with David O’Reilly’s Mountain. This game would plumb the unthinkable question of what it’s like to be anything that’s not yourself. It would wonder what a life connected to alien beings, animal, object, or otherwise, would feel like. Never comfort nor intimacy, but estrangement made bearable by curiosity and wonder. Whether there are thousands or just one, what does it mean that there is such a thing as a pigeon?

Hatoful Boyfriend could have been that game, but it’s not, which makes it emotionally familiar and conceptually inert. There’s a lot to like about Hatoful Boyfriend––the couple of hours I’ve spent in the PigeoNation were both jocular and surprisingly affecting––but it’s hard not to think about what it could have been. There are moments when Hatoful Boyfriend teases us with passing observations on the difficulties of connections between beings that are alien to each other. In one scene, your character is prohibited from participating in a three legged race on account of your physiology. In another, a date to a fireworks show goes horribly wrong when your companion “succumbs to his feral instincts” and flies into the explosions above. Moments like these, when the experimental chasm between two beings is made most apparent, are when Hatoful Boyfriend is at its best, but they are by far the exception and not the rule. When it comes down to it, there’s nothing especially alien about these particular birdies. Deep down, under feather and fluff, they are just like us: human, all too human.