Your adventurers battle a band of goblins upon a paper field. This would traditionally occur on a tabletop in a game store or someone’s home, a troupe of roleplayers managing to finally get together, huddled around their lengthy character sheets and stacks of rules books. But more and more, people are roleplaying online. And developers are finding ways to make more accessible games with simpler rules that leverage the reach of the Internet to get that thrill of miniature battle anytime, anywhere.

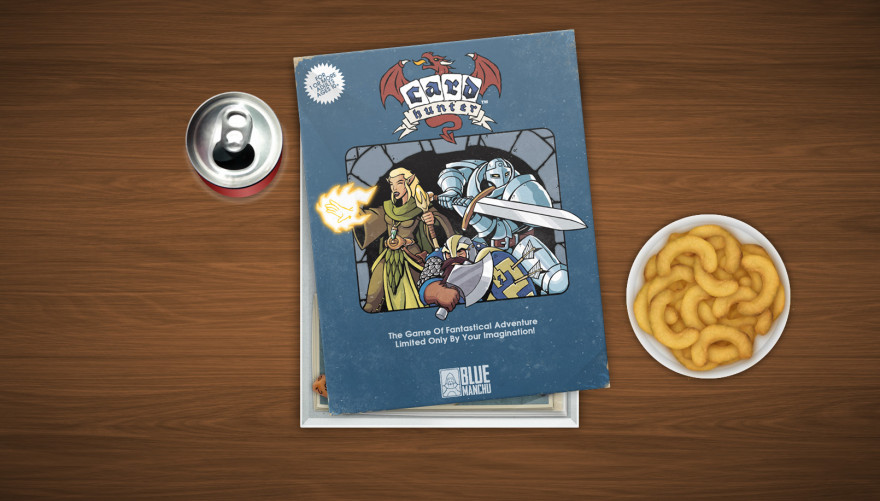

The newly released Card Hunter does just that, but rather than play to the conventions of a videogame RPG, it weds online browser-based play to the mechanics of a collectible card game. You and your opponent take turns playing cards on a wood-grain table. Snacks are illustrated on-screen; dice move around the table depending on who used them last.

There’s also a campaign mode with D&D-esque adventures and online multiplayer, complete with leaderboards. The result is a hybrid that feels equal parts Magic: The Gathering, Shining Force, and actual, in-person Dungeons and Dragons. It scratches several itches at once, and all it requires is a web browser.

The creator of this melange is Jon Chey, one of the writers on the original Bioshock. After helping to revitalize the first-person action-adventure game, he wanted to try to fix another genre: the online card game. His goals were threefold. “Firstly,” he said, “to make a collectible card game where you could win cards by playing the game instead of just buying them. Secondly, to develop a new card gaming system that would present a fresh set of tactical and deck-building challenges. And finally, to put in a level of UI polish that I thought was lacking in existing games in the genre.”

He spent years working out the gameplay, enlisting former colleagues that worked on Bioshock to his new studio Blue Manchu. The first prototypes were made with actual physical cards. “I used plastic figures I had lying around and printed cards,” he told me. “I’d invite friends round and we’d play the game on my tabletop to try to get a sense of whether it was an interesting idea at all.”

As the design process continued, Chey enlisted game consultancy Three Donkeys, which is when when Richard Garfield came to the table. Garfield is a veteran of card games, board games, and a handful of videogames, but he is best known as the creator of Magic: The Gathering, the venerable collectible card game that continues to thrive 20 years after its release. Garfield would work on how the various cards (equipment, spells, skills) work together and allow different strategies.

Even from the initial prototyping stage, Card Hunter’s creators were able to reap the benefits of a hybrid card/videogame. “Prototyping is easier with paper. The constraints of a paper game force you to be very focused and disciplined about the mechanics you use,” said Garfield. “You have a lot more freedom with a computer game—freedom which is easy to overindulge in and can burden the game with unnecessary complexity.”

Being a videogame, rather than a physical game, also made it easier to teach to new players. Garfield said, “Having the computer hold your hand through a tutorial, highlighting your options and not allowing you to select illegal options, makes it much easier to teach a game.”

Likewise, the computer can automate a lot of the tedious minutia that is annoying in real life. The game involves bundling cards together and using them as equipment, so equipping and un-equipping them could involve a lot of management in real life. Instead, that can happen automatically. “Computers are great for handing off boring tasks to,” said Chey.

Skaff Elias, another Magic: The Gathering alum and designer at Three Donkeys, celebrates the digital medium’s capacity for “matching people across the world to play against each other, and the ability to put out new content much easier than with a card game due to real-world distribution challenges.” The convenience of online play lets players who otherwise can’t get a gaming group together on a weekday indulge themselves.

Still, there’s something to be said for the tactile quality of playing cards, not to mention all the snacks and ephemera that the game lovingly recreates. For his part, Garfield believes the fact that the computer handles busywork like calculations, shuffling, or die rolling will win them over. “Converts to online gaming say they can’t go back because the gameplay is so much faster online,” he said. “When they do go back, they will realize they missed the feel of the actual cards, and that may bring them back from time to time, but it isn’t generally as crucial as they first imagined.”

But there is a benefit to tactility beyond actually playing the game. After all, it is tricky to be a “Collectible” card game if everything is virtual. Elias said, “It’s much easier to become a collector in the physical world. The physical object has some inherent, visceral value that a computer card doesn’t. And friends at school can simply hand you a few cards to start—and that’s historically been a very powerful point of entry for card games.”

So with a videogame providing a virtual table, a virtual Game Master, and virtual cards, are actual card games doomed to go extinct? “Definitely not! I don’t think that we will ever replace the social interactions that you get in a face to face play session with other people,” said Chey.

Garfield said, “The social element of being in the same place as your friends and playing together is something cards, and board games, do very well. That said, games like Card Hunter show what computers can bring to traditional game players in a way that traditional computer games never have.”