The best game music transcends the console. People who have never picked up a controller can hum the theme from Super Mario Bros. Portal 2’s soundtrack is a creative triumph, and I still listen to it on its own. Orchestras around the world perform music from Final Fantasy and Zelda because of their quality and their broad popular appeal.

Frequently, however, the use of music in video games is cinematic in the best and worst senses – it can shape the mood of a game, but the reverse isn’t often true. Listening to game music as an album in iTunes underscores the fact that when I’m playing the game, I’m listening to the same unchanging sound files, the musical equivalent of a cutscene. Music in games is more often manipulative than manipulated.

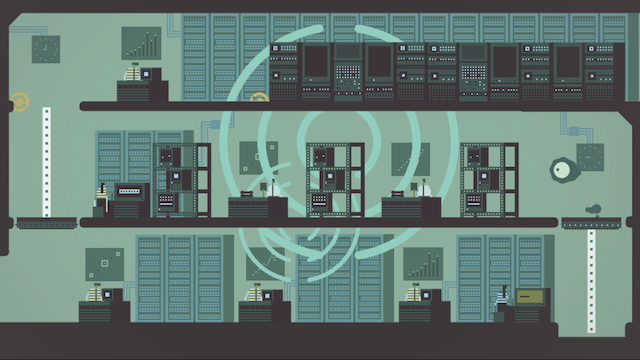

It doesn’t have to be this way. According to Queasy Games designers Jonathan Mak and Shaw-Han Liem, one of the motivations behind the 2D platformer Sound Shapes was to create a game in which the music was more than just a backdrop.

“We were trying to put musical power in the hands of the person who is just playing the level,” says Liem. “Beck writes a song, and in a normal game, that’s it. You just hear it. In Sound Shapes, you’ll never hear the song that Beck made. You make the song happen, so you’ll only ever hear your version of that song, and every time you play it the arrangement will be slightly different.”

The primary mechanic at work in Sound Shapes is participation.

Designers, says Mak, “take for granted this great feeling of making something. It’s not complicated to write music. Everyone can have this great experience. It was important to choose a genre like the 2D platformer that’s kind of universal, as a way to stealthily add in this musical aspect.”

“Interactive” can mean very different things across the variety of gaming experiences, and there are really great games that basically offer the player no choices at all. Most platformers fall into this latter category, and rely more on skill challenges and collectibles to drive player interest.

In Sound Shapes, there’s no real score. And while completing a level lets you access its design elements in the level builder, the dots you collect throughout a level adon’t serve any purpose outside the level, and the musical elements they generate only last for a few screens within the level.

The levels themselves are not especially difficult. There are challenging sections, but as a whole, the design wants to move you forward through the level rather than to keep you from progressing.

Rather than either difficulty or collection, the primary mechanic at work in Sound Shapes is participation.

Hazards and other environmental items often act as rhythmic or musical elements. Quadrilaterals explode in time. Platforms sing the words “move a little, break a little, hurt a little” as they move, jumble, and grow deadly red spikes. Rolling across a line of boxes can create a cascade of notes. The level editor allows players to create their own compositions from whole cloth, but by forcing the player to add each element individually in real time, even the included “campaign” levels (organized into albums, natch) make the act of play a musical performance.

“The level itself is like a interactive animated musical score,” said Liem, “where the screens represent an arrangement through time. By looking at a level you can see exactly how that song is put together, it’s like looking at the score of the music. As you play you’re actually literally looking at instructions on how to make the music.”

“You can experiment with going part way through the level and then going back, or just getting the bass notes but never getting the drum hits. There’s no correct way to complete the level, and it gives you a way to experience the music where you’re taking part in it.”

Sound Shapes gives the player a seat at the table with the designer and the composer, controller in hand, remixing as you go. It a new way for game music to transcend games.