Acclaimed animator Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) is a story of learning to live in harmony with nature—without destroying it. It’s whimsical and heartfelt, an unmatched adventure fantasy unlike any other animated film of its time. Nausicaä predated the continued magic that animation powerhouse Studio Ghibli (co-founded by Miyazaki) has produced over the years, including Miyazaki’s consistent environmentalist-focused fantasies and the low-key realism of Isao Takahata works. It stands as one of the single-most influential animated films of all-time. In the first full-trailer and gameplay footage of Nintendo’s highly anticipated The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, its style looks homeward.

While comparisons to the Western Elder Scrolls series are apt (regarding the game’s widened scope and new crafting focus), the new Legend of Zelda’s visual style remains anew. Not quite as adorable and strongly cel-shaded as the remarkable Wind Waker (2002), nor as bleak and drab as Twilight Princess (2006). Instead, Breath of the Wild finds its stylistic footing somewhere in between—similar to Level-5 and Studio Ghibli’s heartwarming RPG, Ni No Kuni (2010).

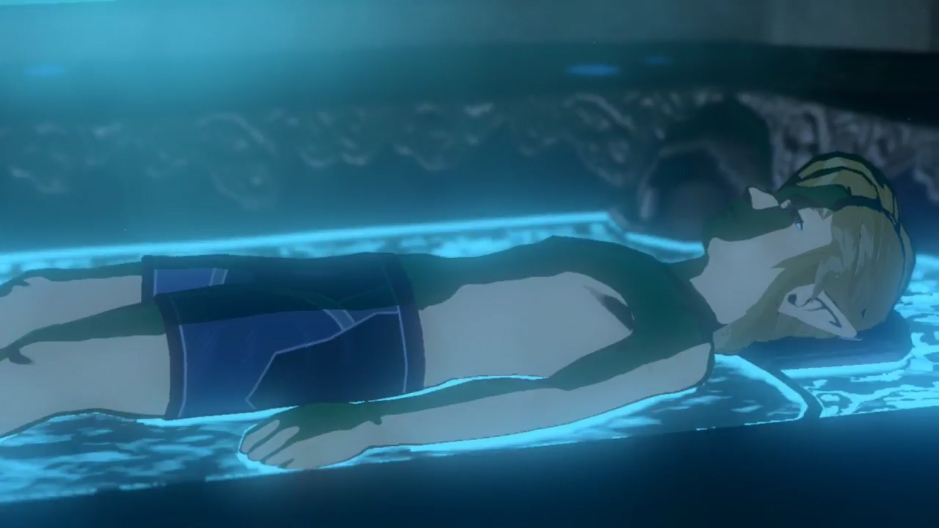

In the first lengthy footage revealed from Breath of the Wild, we see Link waking up (as he always has). But instead of resting in a bed, Link’s in a bizarre pool of sorts. Dressed only in bare boxer briefs, Link awakens in this ominous navy-hued shrine. From the get-go, this scene draws similarities to the mystical qualities of Nausicaä’s environment-endangered world. Link’s new world isn’t the Hyrule we’re used to—there’s new creatures and fantastical qualities at play. As Link emerges from the shrine, he views a full panorama of his volcano-inhabited surroundings. And boy, is it gorgeous.

One of the primary species in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind are that of the feared and endangered Ohmu. The humans in Nausicaä fear the Ohmu, but the titular princess does not. She travels to the Toxic Forest the Ohmu reside in in an effort to find a way the two species and co-inhabit the Earth in peace. In the first peek at Breath of the Wild footage, not only do environments appear Nausicaä-esque, but even characters themselves do. Perhaps most notably: the tentacled “Guardian” (which will also become an Amiibo when the game launches next year).

Among other aestheticized similarities to Nausicaä are the stylistic simplicity in the game’s Japanese logo, and in the Joe Hisaishi-musings of the game’s piano-keyed soundtrack. Breath of the Wild seems most keen to rest its roots in the massive open-world environment that’s promised. Link must craft, scavenge, and hunt to survive (even if the last is optional). Link must fully respect his environment—or respect the breath of the wild, as the game is titled—to reside in it, just as Nausicaä did. So maybe, just maybe, the implied Nausicaä-ness of Breath of the Wild isn’t just an outlandish surface comparison after all.

Nonetheless, The Legend of Zelda series has always been rooted in fantasy. But with each installment, Nintendo bends just what that fantasy entails. Link and Zelda can reside within parallel realities of the ever-changing Hyrule, just as they can in skyward islands where giant birds are the primary mode of travel. The Legend of Zelda has no rules to adhere by per game. Just that there’s Link, there’s Zelda, and there’s an evil to be eradicated. And I’ll probably cry at some point.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, releases on Wii U and NX in 2017. But will we ever find out what the NX is? I’m doubtful.