I don’t know precisely when it was I realized that I suffered from depression, but it certainly wasn’t from playing a videogame. Maybe it was from watching a red-haired, mecha-piloting girl mentally tear herself apart under the weight of her own expectations, and feeling a similar sense of despair in my own weighty ambitions that I failed. Maybe it was from re-reading the same fantasy novels about a particular boy wizard over and over again, feeling that the only escape I ever had from reality was in those books. Maybe it was from listening to early 2000s emo bands that obviously listened to a lot of The Smiths, and were the soundtrack to some of my most socially anxious years. Though most likely it was just the feeling of melancholy creeping up on the most unexpected of days, far beyond my teenage years, feelings I had earlier misguidedly ascribed to “just puberty.”

Depression is seldom implemented successfully into videogames. As a mental illness, it’s difficult to accurately emulate both for those who suffer from it and those who want to understand it better (not to mention being prone to trivialization if not handled with care and knowledge). Strangely, one of the most successful depictions of in-game depression comes from an unexpected, non-autobiographical place: the Japanese arcade title The Idolm@ster, which released in 2005.

Japan’s Idolm@ster is a bunch of different games wrapped into one tidy package: part raising simulator, part rhythm game, with bits of visual novel sprinkled in. You are a “Producer,” who, with dialogue and training, raise the “tension” meters of the roster of idols (Japanese pop stars). This tension in turn grooms them into fun-loving, do-it-all celebrities. That is, except for the quiet and somber Chihaya Kisaragi. Chihaya is an anomaly among the other girls—she’s a reluctant idol. She dances but hates practicing. She grows frustrated when prompted to change into a different outfit. She half-heartedly grins in the presence of her shadowy, omnipresent Producer, afraid to disappoint you at every turn. She’s asocial, and hardly hangs out with her peers or finds enjoyment in other hobbies (outside of listening to classical music). Instead, she focuses on singing, her only passion in the realm of her broadly defined career as an idol. In an earnest declaration, Chihaya believes that if she could no longer sing, she’d rather die. Singing keeps Chihaya alive. This is because Chihaya suffers from chronic depression, onset by witnessing the death of her younger brother as a child and her parents’ subsequent divorce. While Idolm@ster never takes the step to explicitly label Chihaya’s suffering as chronic depression, it doesn’t need to. The signs are all there.

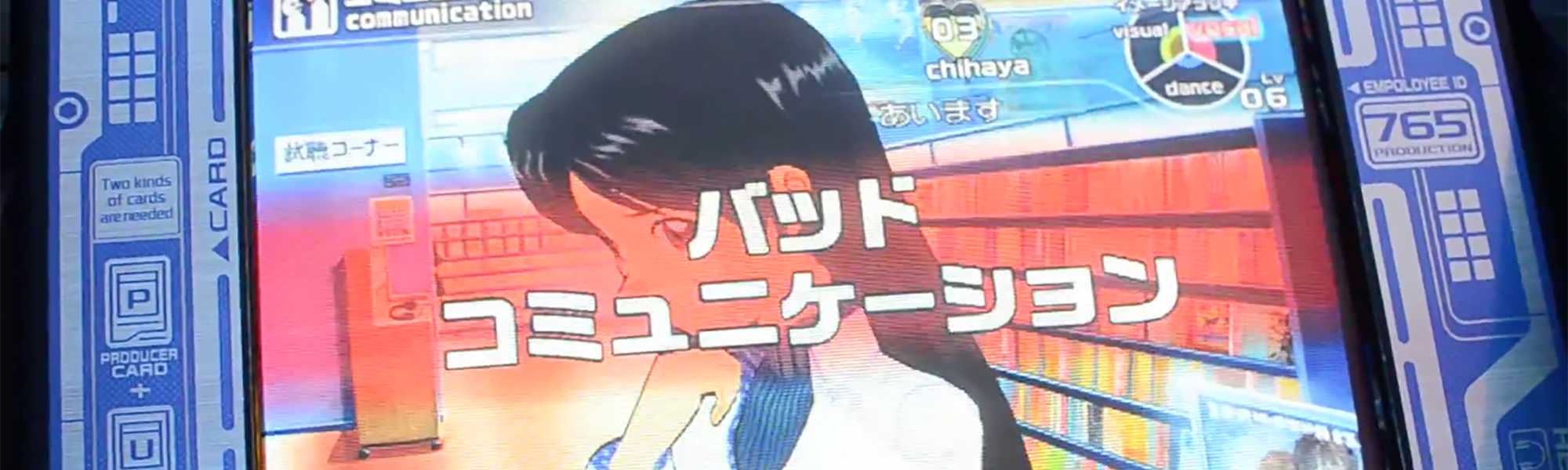

In The Idolm@ster series, you group specific idols from the 765 Productions team together for training sessions. Where some members’ talents complement each other per song more than others, you, as the ever-vigilant Producer, must be flexible in the choices you make. Most girls are balanced in their skills, but Chihaya is different: her Visual and Dance stats are abysmal. Yet her Vocal stats are maxed out—exemplifying her stubbornness when it comes to being a self-proclaimed vocalist first, idol second. Her “tension” meter barely snails along, even at its best, and plunges dramatically if she doesn’t clear a song with a good score. If you fail to greet her, or don’t respond to her in a way she anticipates, you must idly watch as her self-esteem and desire to sing plummet. You try and try again, insensitively wanting her to do whatever you ask. Eventually her tension can drop to a low state indefinitely, as she sinks into a state of despair. Abstaining from her typical idol-activities, you become relegated to a bystander rather than someone actively sculpting Chihaya’s day. Your encouragements never befall any miraculous resolution. You become obsolete in this act, a mere witness to Chihaya’s battle with depression, unable to “save” her in any way. Idolm@ster fans have dubbed this series of events as the “Chihaya Spiral,” the rare permadeath of the rhythm game variety. This is Idolm@ster using Chihaya’s personal struggle with depression as an astoundingly accurate in-game function.

Idolm@ster isn’t the only game to implement depression into its core mechanics. Probably the most widely known game to emulate the illness is the 2013 text adventure Depression Quest, an interactive journey through (you guessed it) navigating life with depression. There are no happy routes or endings in Depression Quest, only the thoughts that plague your mind while trying desperately to maintain a semi-normal life. Depression Quest is not alone in its stark depiction of mental illness. There’s a plethora of other recent, likeminded “empathy” games (perhaps better regarded as interactive “tools”) seeking to help players both cope with and understand depression. There’s Macrodepression (2014), which explores the feeling of being trapped within the familiar prison of one’s own room. 2013’s Actual Sunlight (warning, spoiler:) follows the mundane day-to-day life of one man, ominously leading to his apparent suicide. The upcoming Healing Process: Tokyo aspires to simulate a Tokyo-based surgeon’s battle with regaining happiness, having lost his wife in a tragic accident.

While not namely focusing on depression, a game mechanic of grief is implemented to the 2013 adventure game Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. Throughout the game, you are controlling two brothers: one using the left analog stick, the other using the right. During a climactic moment—spoiler alert!—one of the brothers dies, and you effectively lose half of your mobility as a result. Having played the game entirely to this point with the two characters, the loss of one half resonates powerfully in a way that wouldn’t have been the same if it were merely a story beat. You, the player, have lost your other half, and you feel it.

While these games seek to ease you into the experiences of the characters’ suffering, they differ from The Idolm@ster’s outsider perspective. Being Chihaya’s boss (the Producer), you hope to be perceived as Chihaya’s friend. Through the mechanics of not being able to shape Chihaya as you normally would with the other idols, her emotions are given more weight; she feels singular in her actions. In another raising sim/rhythm game like Project Diva F (2012), you can feed a Vocaloid, such as Hatsune Miku (another digital idol), a food they don’t like, and they simply pout in disgust. Whereas in Idolm@ster, Chihaya grows increasingly emotionally unstable at the turn of a conversation or after a bad training session or concert, and the reality of her ongoing interior suffering dawns on you, time and time again.

Idols beyond the digital world have long been a symbol of all things cute in Japan. They smile brightly, bend and twist into coy poses for photo ops. Their wholesome, adorable image is reinforced by their saccharine singing, dancing, and television appearances. Idols embody more than just being musicians: they’re the everygirl’s role model. The underdog who was able to make her dreams come true. Though in some cases, this outside sunny demeanor is just an elaborate facade, a mask to hide behind in hopes of building a marketable career.

Perhaps most notable of this complex professional existence is that of 1980s teen pop idol Yukiko Okada, who committed suicide when she was just 18 years old. Okada was young during her rise to fame, winning the top prize of a televised talent show in 1983, which propelled her into Japan-wide fame. Okada went on to sing jingles for commercials, top the Oricon charts (essentially Japan’s Billboard) and even star in a Japanese drama series—then she leapt from the seven-story Sun Music Agency building. Okada was not vocal prior to her death about her now-speculated struggle with depression, yet her suicide singlehandedly shattered the “perfection” that idols were seen as in the industry. Her shocking death was one of the first to shed light on the staggering trend of depression and suicide in Japan.

As a popular idol in the peak of the 80s “idol period,” Okada wasn’t given much room to be herself at all, and only existed to the public as the smiling teen dream her management sculpted her into being. Chihaya, like the other idols in Idolm@ster, is in contrast given a personality behind the idol facade, and given her own sense of agency in the behind-the-scenes nature of the game. She exists beyond the title of just being another interchangeable idol, as so many popular idol groups (such as the massive AKB48) are seen as today.

With Chihaya’s gameplay arch, Idolm@ster builds a new narrative, defying the depression recovery narrative that plagues many films and television shows of today. In the overwrought depression recovery narrative, victims can eventually “overcome” depression. Whether the “cure” is through medication, therapy, or just good ol’ epiphanies, it’s almost always followed with a shoulder shrug of the bout of depression merely being a mark of “past” suffering, never looking to the future. Idolm@ster looks to the future, the past, and the present of living with a mental illness. It doesn’t sugarcoat Chihaya’s disposition, it simply presents her pain as one part of an unbridled look at a human being. Chihaya’s depression, like all depression, is all encompassing.

Despite the existence of the Chihaya Spiral, it’s important to note that Chihaya isn’t perpetually in despair. When she succeeds, she still inches forward, her tension meter snails its way upward. She has her good days, just as she has her bad days. Chihaya is not solely her depression. She exists beyond her illness with the admiration and respect she feels deep down for her peers, for her late brother, for her craft. While the anime counterpart of Idolm@ster narrowly sidesteps the trope of “overcoming” her depression, Chihaya effectively channels the grief she feels for her late brother into her music, culminating as a powerful song. In the later, non-arcade Idolm@ster games, there’s no game-crushing Chihaya Spiral, though she does remain one of the harder idols to train to perfection. She’s relatable in the sense of the duality of her personality. She suffers, but she shines, just as I do and everyone else that suffers from a mental illness. It’s a clear example of the power of an interactive and playable medium, versus film or literature, and its ability to transport players into a situation they would not otherwise find themselves—or happen to live everyday. Depression will always be around for Chihaya, but in eventually opening up, she feels at least a little more free.