“Where have all the kids gone?” read the headline. It was September, 2014. The school year was starting and Detroit’s High Schools were looking for football players. Detroit Western head coach Andre Harlan told Soo Detroit that “[the] majority of the teams in the league have struggled with low numbers.” His counterpart at Pershing High School had scheduled a summer practice only to have seven kids show up. So, the headline asked, “Where have all the kids gone?”

One answer to that question is that the kids and their parents have left Detroit.

In 1950, Detroit’s population peaked at 1,850,000 residents. The city’s booming auto industry offered its employees generous wages and benefits, allowing their families to cement their position in the middle class. During its heyday, Detroit stood out as the embodiment of a functioning industrial city.

The Motor City now has 688,000 residents. Carmakers long ago decamped to other cities or, in the case of Studebaker and Packard, ceased to exist. Over 90,000 lots sit vacant. Calls for ambulances sometimes go hours without being serviced. Last year, Detroit became the largest city to ever file for bankruptcy. Any day now, four in ten Detroit residents could have their water shut off.

As Detroit’s football coaches are learning, the struggles of a game and of a built environment can be one and the same. When groups fall apart, as teams in Detroit’s PSL have, people start to ask what is happening and what can be done to bring the disappeared back. But first they ask where these people have gone.

///

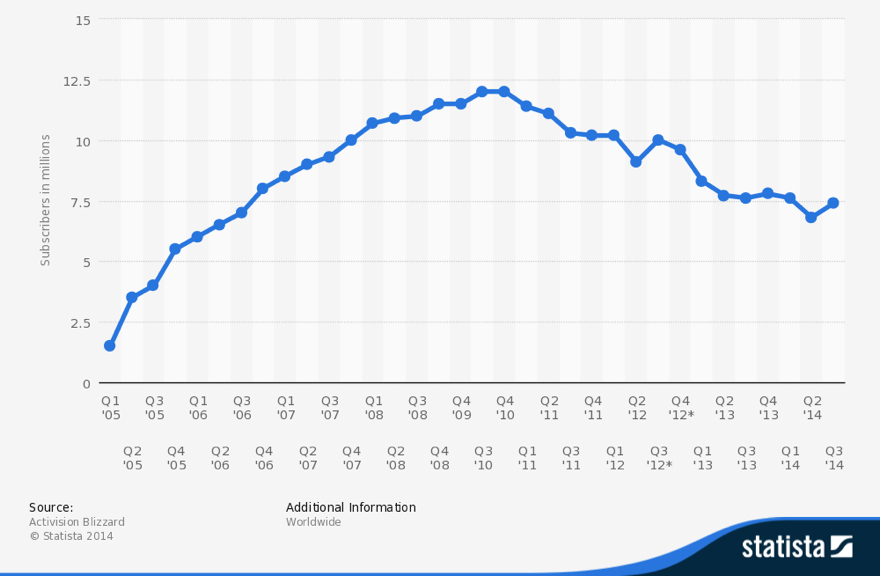

If tomorrow morning a giant tidal wave swelled in the Gulf of Mexico and washed away every resident of Louisiana, America’s population would decline by the same amount World of Warcraft’s has in the last four years. 4.6 million subscribers have left the shores of Azeroth in that time. In what passed for a good quarter, only 100,000 were washed away in the fall of 2013. Between March and May 2014, a staggering 800,000 subscribers disappeared beyond the horizon.

Only a game of World of Warcraft’s size could experience such losses. In October 2010, Blizzard Entertainment’s flagship game counted 12 million subscribers. After a two-year wait, the game’s second expansion, Wrath of the Lich King, had just been released in China, adding the continent of Northrend to the game world. In the world of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs), World of Warcraft redefined “massively.” Only WoW has reached these heights; only WoW has lost so many subscribers.

Since World of Warcraft’s subscription numbers started to tail off, only two quarters have bucked the downward trend. In September 2012, Blizzard released a fourth expansion set, Mists of Pandaria. That fall, World of Warcraft added 900,000 subscribers. This resurgence proved to be short-lived. World of Warcraft’s population shrank in each of the next seven quarters. World of Warcraft’s latest expansion set, Warlords of Draenor, was released on November 13, 2014. The quarter leading up to this release saw the game add 600,000 subscribers.

The outlook for World of Warcraft is therefore murky. When compared to other pay-to-play MMOs, it remains astonishingly popular and lucrative. Yet its audience and revenue have been declining for years. These two realities cannot coexist forever. Warlords of Draenor will either usher in a lasting resurgence or have as fleeting an impact as Mists of Pandaria. On the occasion of its tenth anniversary, World of Warcraft is waging a battle against the ravages of time that few games live long enough to face.

Warlords of Draenor introduces a new map to Azeroth but the world of gaming offers few points of reference for understanding what it all means. World of Warcraft’s predicament, however, is not unheard of. The struggle to reverse declining population and revenue figures is a common one. So too is the question of whether to make up for an exodus by attracting newcomers or urging the diaspora to return. This question leads to another: towards what ends should scarce revitalization resources be allocated? The questions Warlords of Draenor must answer are, in other words, the same questions Detroit has been struggling to answer for decades.

///

The Motor City has spent the better part of the last fifty years attempting to reinvent itself. In 1967, over the course of five bloody days of rioting, the city’s longstanding economic and racial tensions came to the fore. The Army and National Guard fought in Detroit’s streets. 42 people died, 1,189 injuries were reported, and more than 7,200 arrests were made. At least 2,000 buildings were destroyed. Shortly after the riots died down, Detroit mayor Jerome Cavanagh visited their epicenter and observed, “Today we stand amidst the ashes of our hopes.” Thenceforth, construction gave way to reconstruction.

In the riot’s aftermath, the city’s leading businessmen banded together to form a development organization messianically entitled Detroit Renaissance. Led by Henry Ford II, they moved for and financed the construction of the Renaissance Center. Billed as a “town within a great city”, the Renaissance Center was composed of five towers that rose from a pedestal that housed shopping and entertainment facilities. Four office towers encircled a hotel tower that, when it opened in 1977, was the world’s tallest hotel. Seeing as the Renaissance Center was meant to symbolize Detroit’s rise from the dead, it is only fitting that Jimmy Hoffa’s corpse is rumoured to be buried in its foundations.

Much as World of Warcraft points to its still-large subscriber base, a promotional video released by Detroit Renaissance in the 1970s highlighted the city’s status as the world’s fourth-largest financial centre and 31 colleges and universities. “Detroit’s pace and tempo are like that of any great city,” the narrator cheerfully intoned. The video sold a bright future by downplaying a difficult present.

The promotional video epitomized Detroit Renaissance’s failure to architecturally and intellectually engage with the problems they sought to fix. As a self-contained ecosystem, the Renaissance Center allowed its occupants to stay well clear of the city it was meant to revive. It therefore did little to reverse Detroit’s (primarily white) urban exodus. Its design reinforced this sense of hostility towards the urban environment. The skyscrapers cowered in fear on their pedestal. The four office towers surround the hotel, shielding its occupants from the city’s streets. Artist and native Detroiter Mitchell Cope describes the complex as “a modern-day medieval fortress” in his essay Fortification in Downtown Detroit.

Who would buy property next to Noah’s Ark if it were equally feasible to run for the hills? The Renaissance Center, like the biblical craft, was a life vessel that doubled as a harbinger of imminent doom. It is a reminder that revitalization is about optics as well as physical realities. Its construction did as little to bring Detroit’s expatriates home as Mists of Pandaria did to bring World of Warcraft’s former subscribers back into the fold. Building a large edifice is not the same thing as building a bright future.

///

The Renaissance Center’s struggles stemmed from a problem that Detroit and World of Warcraft still face. Revitalization schemes, for all of their lofty rhetoric about new construction and the future, take place in environments that have long and complicated histories. The hands of planners and designers are tied by decisions made years ago. There is no such thing as a fresh start, only reckoning with the past.

So it was with the Renaissance Center, which was built to bring people back to Detroit but existed in a city that was designed to facilitate egress to the suburbs. Starting in 1959, construction on the Chrysler Freeway tore through Detroit’s Black Bottom neighborhood, paving a route out of the city and displacing many of the black residents who lived in its path to 12th Street, the eventual hub of the 1967 Riots. This sequence of events created the climate that triggered the riots and the infrastructure that allowed white flight to rapidly accelerate after 1967. Then and now, Detroit’s problems were structural. No building could reverse decades of urban policy decisions.

World of Warcraft is as wedded to its past as Detroit. This is not a romantic marriage so much as one where two people stay together because it’s easier than figuring out how to divvy up the assets. “[Warlords of Draenor] isn’t a time travel expansion,” WoW lead designer Ion Hazzikostas told CNET, “we don’t get into any weird timeline continuity stuff.” In theory, Blizzard could throw continuity and caution to the wind. But doing so would erase much of what has made World of Warcraft popular over the last decade. In game design as in urban planning, there are no mulligans.

The structure of World of Warcraft is largely set at this point. Most MMOs are now free to play, generating revenue from in-game microtransactions but World of Warcraft remains a pay-to-play offering, as it has always been. Its timeline, as Hazzikostas explained, is largely set. Expansions need to be fitted around past installments. The same is true spatially; Wrath of the Lich King added a continent to the game world. It is always easier to build on the periphery than in the center.

The comparative ease of construction on the outskirts is the story of Detroit as well as World of Warcraft. The homogeneous communities that white Detroiters fled to after the 1967 riots could easily be built from scratch. As the Renaissance Center proved, building in the city takes time and is unlikely to change the larger urban fabric. It takes a long time to unwind decisions made in the past. Revitalization, by its very nature, is a piecemeal process.

///

Who, in 2014, are World of Warcraft’s target audience members? Many of the subscribers who played the game during its pomp are now gone and those that remain have grown up. “The person who picked up the game in 2004 who was a student with tons of free time is now a career person with a family,” Hazzikostas told CNET. “They’re [now] trying to fit in 60-90 minutes of game time after the kids go to bed at night.” If this core demographic has evolved, should World of Warcraft adapt to their needs or look elsewhere?

Prominent urban theorists have encouraged communities to stop pining for old residents and start importing new, desirable demographics. In his book, The Rise of the Creative Class, Richard Florida argues that attracting members of the “creative class” — artists, bohemians, tech-types, musicians, gays, lesbians — is the key to urban regeneration. Florida decries “building generic high-tech office parks or subsidizing professional sports teams.” Instead, he notes “location choices of the creative class are based to a large degree on their lifestyle interests.” A city that wants to attract members of the creative class, which, in Florida’s estimation, is any sensible city, must appeal to those interests.

Last fall, after a year of construction and $4.2 million in tax credits, Detroit’s first Whole Foods opened in Midtown. Dressed in full regalia, a marching band entertained the eager customers who had started lining up three hours before the scheduled opening. In the video of the event released by Whole Foods, a man in the crowd wipes away tears of joy. At 9:00 am, instead of cutting a ribbon, the assembled dignitaries and employees literally broke bread—a long, multicolored, braided challah loaf, to be precise. “This is a new beginning,” proclaimed Mayor Dave Bing.

The Midtown Whole Foods was but the latest in Detroit’s long line of new beginnings. This claim to fame had previously belonged to the Renaissance Center in the 1970s, the Republican National Convention in 1980, the new stadiums built for the Detroit Tigers and Lions in the 1990s, and the hosting of the Super Bowl in 2006. In all of these cases, public funds were invested in flagship downtown developments in the hope that businesses and ex-residents would follow their lead and return to downtown Detroit. In addition to being failures, all of these projects can be described as Richard Florida’s worst nightmare.

Now, Detroit, like many of America’s struggling industrial cities, has thrown in its lot with hipsters, gentrifiers, and tourists. It now has a Whole Foods, a yuppy beacon in a food desert. Other new developments include a museum of contemporary art (MOCAD), microbreweries, cafés, and a restaurant that serves a tasting menu where each course is paired with a track from Radiohead’s Kid A. In recognition of these developments, Fodor’s compared Detroit to Brooklyn when listing it in its “Go List” for 2014.

///

Buzzworthyness has a tenuous connection with revitalization. A new microbrewery is not actually a sign that a city like Detroit is regenerating; it is simply proof that the city has another microbrewery. The conviction that such developments have deeper meaning is sometimes decried as “hipster capitalism.” The historian Thomas Sugrue calls it “trickle-down urbanism.”

Sugrue was raised in Detroit and went on to write The Origins of the Urban Crisis, an account of his hometown’s decline and the many efforts to revive it. In Sugrue’s estimation, the opening of a Whole Foods and ongoing hipsterfication of Detroit is a continuation of the thought process that led to the Renaissance Center being built in the 1970s. “Efforts to remake the downtown as a convention and entertainment zone,” he writes, “did nothing to stem the demographic and economic forces that were devastating the city.”

Revitalization efforts of either the Richard Florida or Detroit Renaissance varieties, Sugrue argues, tend to be purely cosmetic: an office complex here, a bike shop there. “It has become commonplace today to gauge the health or success of a city on its visible gentrification,” he decries, “even if there is little evidence that these islands of prosperity do much to transform the urban economy or benefit the majority of the population.”

Sugrue’s critique of urban regeneration is fundamentally concerned with inequity. He notes that the gentrification of Detroit has prioritized the needs of small white communities in a city that, in 2010, was 82.7% black. These new businesses may create some low-paying jobs (70% of Midtown’s Whole Foods’ employees live in Detroit) but offer few opportunities for advancement and can never be expected to replace the city’s former industrial base. No aesthetic tweaks can overcome these structural problems.

///

Detroit is not Azeroth. It cannot be rebooted or spun off, as World of Warcraft was from the Warcraft games. The underlying mechanics of a city, unlike a game’s graphic engine, cannot easily be upgraded every few years. Municipal governments are positively byzantine when compared to development studios. All of these factors make it harder to revitalize a city than a game.

But if it was so easy to revitalize video games, why aren’t there more stories of games that have come back from long period of decline?

The language of urban regeneration is also the language of videogame revitalization. The context shifts but words and concepts remain the same. Revitalization, wherever it happens, is about construction and constraints. It is the study of possibility tempered by historical realities. The questions revitalization efforts raise are similar. Who should an expansion set serve: die-hard players, newcomers, or the returning family man? Who should Detroit’s regeneration efforts serve: the urban underclass or incoming hipsters?

In games and cities, revitalization efforts allocate resources to address certain needs and demographics at the expense of others. Ideally, regeneration programs would tend to everyone’s needs. But neither Detroit nor Azeroth fit that billing. Both iconic communities wish that the masses would return but have yet to prove that they can bring them back.

Warlords of Draenor may yet buck that trend. Blizzard claims to have added 3.3 million subscribers since the end of October. For the first time in four years, World of Warcraft could grow in consecutive quarters. If this happens, Detroit may want to take a few lessons in revitalization from the likes of Ion Hazzikostas. Yet history suggests that Warlords of Draenor will be another Renaissance Center or Whole Foods, a temporary achievement that fails to make a lasting impact.

MOCAD image via Joe Wolf.