Davey and Stanley have been living together for about five years now, and lately, they’ve started getting on each other’s nerves.

“Stanley is this thing that I desperately need,” Wreden says. “It’s responsible for some of the best things in my life now, but at the same time, I need to get rid of it, to move on.”

The creator of The Stanley Parable has an intimate and conflicted relationship with games of all kinds, especially his own. “Maybe if I’d watched films every day growing up, I would have found a way to express what Stanley Parable is about through film,” he mused. “But I played games.”

The short-short version of his story: Wreden started working on his first videogame, the original Stanley Parable, at the end of his undergraduate course in USC’s film school. Inspired by the Dear Esther mod to try his hand at modding, he started playing around with Valve’s Source Engine, designed and wrote Stanley within it, found the perfect mix of charm and terror for the narrator in Kevan Brighting’s voice, and released something poetic and affecting that blew up online a few weeks after graduation. Now, unintentionally following in Dear Esther’s footsteps once again, Wreden and the Galactic Cafe team are on the brink of releasing The Stanley Parable as a standalone title this October, five years after its inception.

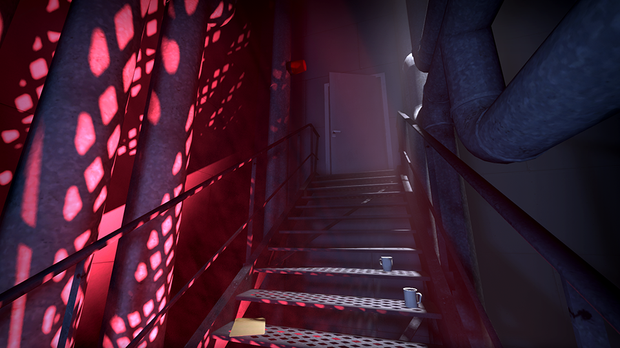

Explaining what The Stanley Parable is can be difficult, even for its creator. Like Bastion, there’s a narrator who explains the player’s actions in specific detail. But, unlike Bastion, where the narrator describes what you just did, a Stanley Parable player can choose whether to obey or disobey the narrator, who describes what Stanley should do, and then responds to the player’s choice. It’s been called a metanarrative and a metagame, but when you’re playing—the narrator directing you, repeating scenes with different outcomes, improvising when the opportunity presents itself—it almost feels like experimental theater.

Because the game really can’t be elevator-pitched, Wreden and Galactic Cafe designed a standalone preview of the game just for PAX that, amazingly, gives a feel for the game (and its designer’s work) without spoiling a thing.

In the beginning of the demo, the player—after having waited in line on the PAX floor for their turn—enters a digital waiting room and must take a number. The narrator promises to show the player The Stanley Parable Demo if they would kindly wait motionless for twenty minutes. Waiting in a real line only to wind up waiting in a digital one reads like a cruel joke, so, when the player inevitably breaks from the waiting room toward the just-out-of-reach demo itself, the narrator intervenes, checking to make sure the disobedient player really understood the instructions so that they can continue waiting their twenty minutes. After disobeying and attempting to see The Stanley Parable Demo time and time again, the narrator relents, letting the player go into the big tempting room they’ve been trying to get into in order to start The Stanley Parable Demo, only to find themselves back in the waiting room, fulfilling the narrator’s prophesy from the Demo Status room: “This device tells you whether or not you’re inside a videogame demonstration. Somewhere around there, there’s also a device that tells you whether or not you’re inside a device that tells you whether or not you’re inside a videogame demonstration.”

All this—including the metagame taking place on the PAX floor—encapsulates both the experience of dislocation central to the The Stanley Parable and, by extension, Davey Wreden’s philosophy of writing and design.

In a certain way, playing The Stanley Parable feels like how I imagine playing World of World of Warcraft might: half puppeteering, half existential crisis. Wreden’s game is so deeply aware of its own artifice that it ceases to be artificial, forcing the player to reflect on the choices, interpretations, and assumptions that define the way they play not just this game, but all games.

I asked Wreden about (very minor spoiler alert!) the decision to let players see Stanley in the opening cutscene. Why separate the player from Stanley, I wondered, in a game where he’s clearly supposed to be us?

“Isn’t that a little self-important of you?” Wreden shot back, smiling. “What if he’s not? What if Stanley is his own person? What if it’s not about you role-playing Stanley, seeing yourself as him, getting talked to by the narrator, but that’s all just what you need from games, what you’re bringing to the table? What if it’s just you and your assumptions and The Stanley Parable and that’s it? People build up these little tepees—these preconceived ideas about games—where they feel safe. But we don’t even know what games are or can be! This is the game fighting back, knocking those ideas down, responding to how you play. That’s your mirror.”

Wreden’s been questioning the assumptions we bring to the media we’re consuming for years. His student film project, “A Film By Davey Wreden”, is about the process of writing and casting and filming a film about Davey Wreden, which is itself called “A Film by Davey Wreden,” which was written by and stars Davey Wreden, which etc.

Having put himself to this task of tearing down tepees for a few years, Wreden’s identified a few of the tools and patterns he uses as an author and designer. “After doing Byrdr”—which was the social network/ARG spoofing Twitter in Ridiculous Fishing that Wreden wrote—“and looking back on my work as a whole, I realized that there’s this pattern to the things I write: funny thing, funny thing, funny thing, emotional thing, inappropriate ending.” But it’s always that ending that turns the lens back on you, asking, “What were you expecting?” without waiting for a reply.

The Stanley Parable is a binary system. You go left or you go right; you obey or you disobey. But that seemingly simple structure opens up a garden of forking paths, opportunities for the player and the narrator to subvert their own expectations. In the best case scenario, Wreden says, “the words turn to ash in your mouth” after you play. You can’t quite explain what’s happened to you while you were playing the game because most of the language we have only describes things we expect. “Sometimes, after someone had finished playing the game, their eyes would light up, like really light up. Especially when they get it, they can’t put it into words. And that’s how I know they got it.”

Like the best satires and satirists, both The Stanley Parable and Davey Wreden are motivated by a belief that their medium can be better if it thinks more critically about what it’s doing, how it’s doing it, and what its audience expects it to do. “I created The Stanley Parable as the kind of game I wanted to play,” Wreden said, though even he still can’t quite explain what that game is because “the language isn’t there.” When it comes out later this month, you’ll be able to see for yourself, Stanley.