As a transgender girl growing up in the American Midwest, childhood was a lonely experience for me. I was still questioning so much of who I was, and at the time, there weren’t many resources out there to help me work through it. Transfeminist literature like Julia Serano’s Whipping Girl (2007) had yet to be published, and I had to resort to older and more unhelpful narratives instead, like a 1998 book a mother wrote about her daughter’s transition titled Mom, I Need to Be a Girl.

Finding myself in a real-world culture that was unwilling to talk about LGBT issues for fear that they were somehow inherently “too adult” for me, I instead turned to the internet in my bid to put words to the feelings inside. Finally, on a few backwater websites with conflicting information and often unreadable fonts, I got my first glimpse of the trans community. It was scattershot and reflected an era when the term “transsexual” was more popular than “transgender,” but its Geocities and Xanga stylings were the first to tell me “You are not alone.”

In her comic Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy, transgender artist and game designer Merritt Kopas describes her own experience of finding herself online, going all-in on a childhood not formed on football fields or even in 7-11 parking lots, but rather through obscure internet forums, blue-haired anime pretty boys, and French ROMS of Japanese fighting games.

The comic, a collection of seven poems illustrated by 28 different artists, opens with a diverse group of blue stick people each living within their own individual red box, which are then connected together by a series of tubes. Their personalities vary from welcoming to decapitated, and it’s an apt representation of the kinds of online environments where many of us spent our formative years. What follows is a coming-of-age story about stumbling upon the forbidden corners of the internet and for the first time being exposed to a culture outside of the real-world that is so often unhelpful to the queer and questioning.

Like Sailor Moon transforming into new outfits, Kopas tries on new identities based on the internet culture around her, making them her own with each morphing sequence. Throughout the course of the comic, she is a shoujo heroine, a half-beaten Saiyan warrior (who kind of likes it), an anthropomorphic dog person, a forum user with a perverse taste for the report button, and a blue-haired anime girl role-playing her way to submissive fantasies she didn’t know she had. For someone desperate to be anyone other than what their culture has assigned to them, the internet is a powerful tool.

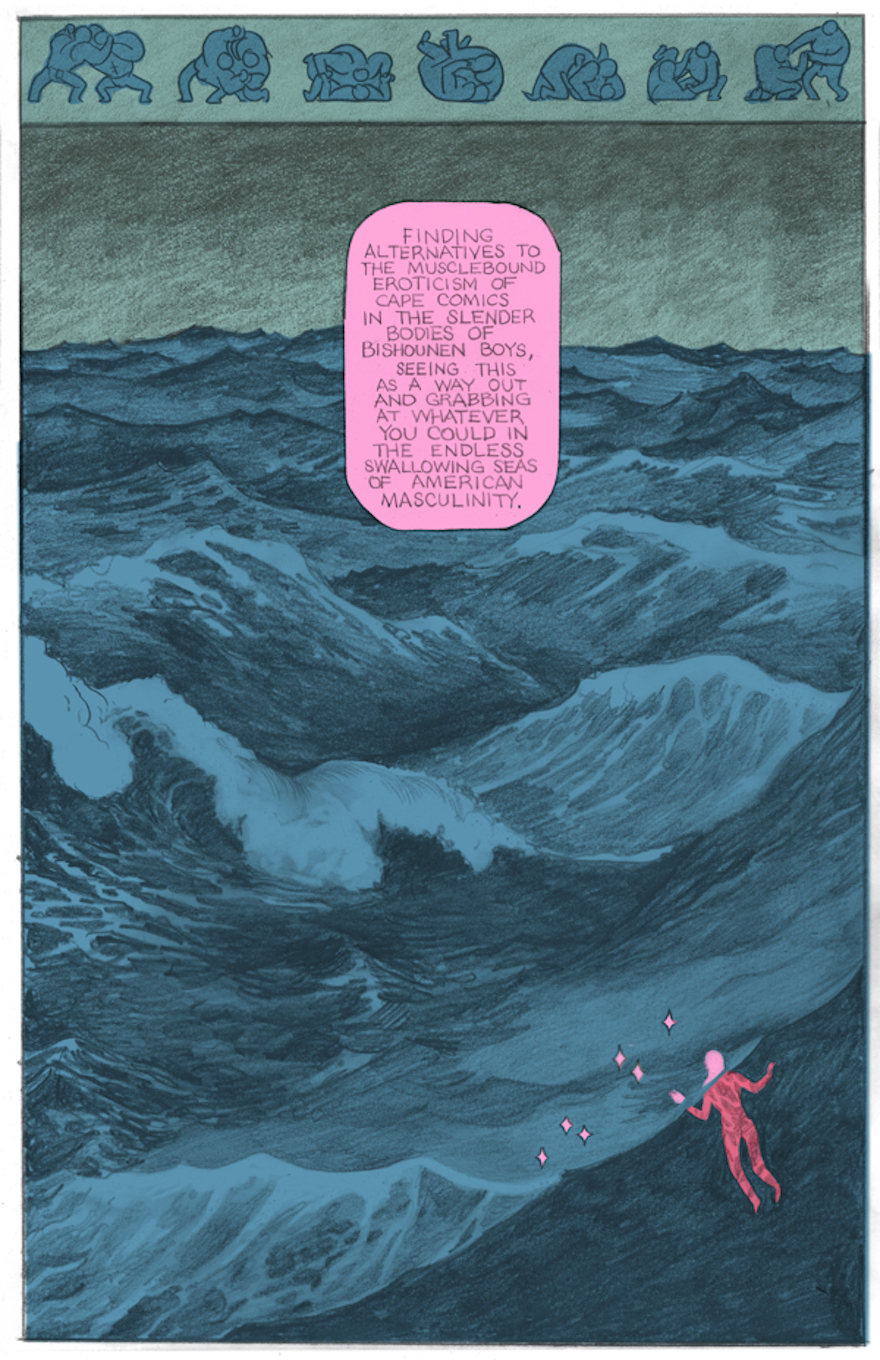

That said, few of the sites Kopas visits are directly related to being trans. Overtly trans themes are peppered throughout the comic, but its most prevalent aesthetic is one of anime. There’s a splash page with an original fan-character pulled from the collective sophomore study halls of a million weebs, a pencil-drawn sketch of a blushing fox boy in a kimono, and always a helping hand from anime poster-boy Goku when times get rough. In “A Bishie Saved My Life,” Kopas dives deep into how the soft-featured, long-haired, androgynous men of anime gave her an avenue to explore her own burgeoning femininity.

“Finding alternatives to the musclebound eroticism of cape comics in the slender bodies of bishounen boys,” she writes. “Seeing this as a way out and grabbing whatever you could in the endless swallowing seas of American masculinity.” Here, Kopas fires back at a culture that often likes to ignore its own sexual subtext with raw sexuality of her own, refined through fansubs and manga scans adopted from a series of islands an ocean away. At the same time, she is an outsider looking in, playing into classic orientalist themes by exoticizing small and unrepresentative scraps of Japan’s culture, and she recognizes this. At a certain point, she had to go back home.

The comic ends with a riff on Blade Runner’s (1982) famous death scene as Kopas recounts her visits to the congealed cumrag of id that is 4Chan. She talks about coming across other trans girls posting nude selfies for the boys to fap over. She wants to embrace them, worried that they have “moulded themselves into subhuman sex dolls,” knowing that it was because “it felt like the only route to intelligibility.” She wants to save them from a community that’ll praise them as sexual objects but refuse them basic dignity as human beings. She’s no longer some scared kid making the text smaller to hide it from dad. She’s an internet senior ready to take the new batch of froshes on tour.

With its many open browser windows and instant messenger clients, reading Kopas’s comic is reminiscent of diving through Nina Freeman’s desktop in Cibele (2015). But if Cibele is a drama about failed romance, then Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy is straight pornography. It’s vibrant, it’s taboo, it’s brazenly erotic, and it’s an open-book look at some of the lesser-discussed “pastimes” that we all had as teenagers (wink wink). For queer audiences, it holds special value as a representation of where many of us first found ourselves—I’ve even put it on my OkCupid profile alongside an “it me”—but it also points to the more general internet Wild West of the ’90s and early ’00s.

As an adult living 16 years into the new millenium, I now spend most of my browsing time on clean, contemporary, “safe” sites like Facebook and Twitter. But as a kid? I frequently sneaked into my family’s computer room at 3:00 a.m. to stream illegal fansubs of terrible body-switching anime from sites that had a 50/50 chance of giving me a virus. My family would have been mortified if they knew, but there’s something to be said about letting the shield down and allowing kids to tread out into dangerous waters now and then. It was there that I learned to swim.

You can buy Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy on Kopas’ itch.io. All proceeds go to her surgery fund.