Jack de Quidt talks about videogames as if they were made out of a fine silk. He describes how they feel to touch, how they smell, and what tastes they bring to the tongue. De Quidt doesn’t just play games but seems to absorb them through his every orifice.

His main interest in the medium isn’t its mechanics or narratives, but in its textures and onomatopoeia. He’s previously spoken fondly of the crunch of snow under boots and the rough feeling of corn against the fingers, stating that in the games he makes the “currency is nostalgia” (not the usual 8-bit videogame type), and also explaining that his fascination with textures is in how they connect us with memories.

This idea is on full display in Castles in the Sky, which was the debut game of UK-based studio The Tall Trees, formed of de Quidt and 10 Second Ninja creator Dan Pearce. It’s a game about childlike wonder, innocence, and dreams, all emerging from shapes in the springy clouds that propel you upwards. It’s short and certainly sweet at just 10 to 15 minutes long. In that time it percolates like a lullaby, leaving a gentle residue upon you in the same way a Boards of Canada song might.

///

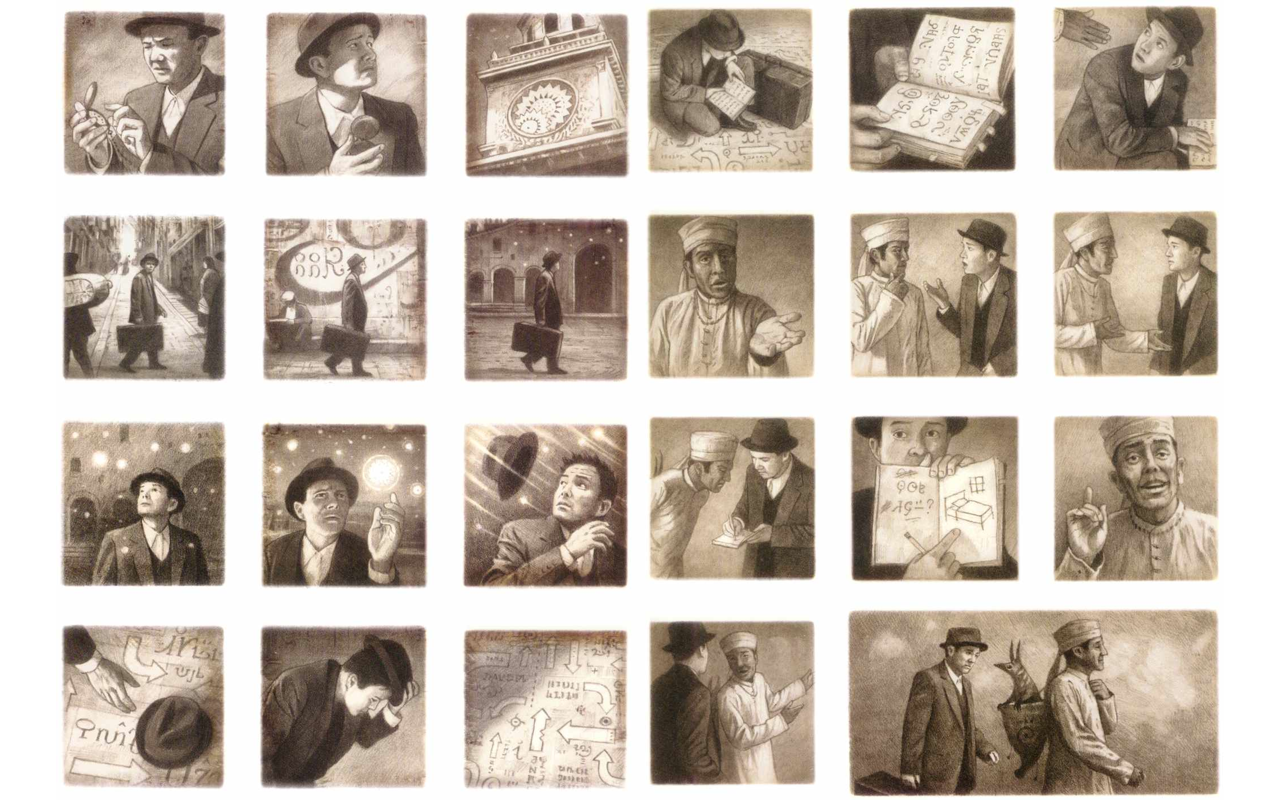

“There’s a phenomenal picture book by Shaun Tan called The Arrival. Really, anything he makes is great, but this is a wordless parable about an immigrant arriving in a fictional, fantastical city, and how he finds himself becoming a part of it. It’s a huge inspiration to me, both in its world design and its non-standard treatment of the medium.”

///

I’d arranged to speak to de Quidt about his latest creation that he describes as a “guidebook game” and that he calls Veracity & Purpose. It was made as a gift for his friend Austin Walker, but is available to all those interested in a “written museum guidebook for an exhibition on a fictional 17th Century Painter.” It focuses on an intimate examination of the paintings and how they relate to their creator, but spans further into something more personal to the fictional character reading through the guidebook. It almost becomes sinister.

“I wanted to make something about art galleries, which are wonderful, surreal spaces in which people walk (generally silently) and stare at paintings for a period of time,” de Quidt says. “There’s something uncanny and magical about being in a gallery, especially on your own, and I hoped to pull some of that out into the story.”

You can play Veracity & Purpose for yourself, but to understand what the game is doing and what it’s about seems to require getting to know de Quidt. He’s young, at 21-years-old, but has spent a lot of time with his head in music and books, especially after being bullied at school. Primarily, de Quidt is a writer and composer and has entered videogames from those fields. De Quidt comes at games from a similar angle as composer David Kanaga, then, whose original scores have given character and variety even to those games largely devoid of it.

De Quidt’s formative experiences with the medium came from playing a lot of early Splinter Cell and the first two Thief games. He says it’s these meticulous and tense stealth games that helped him establish that videogames are as much about the “intangible feel of the place” as they are about mechanics.

“Splinter Cell and Thief have this great feel to them, a sort of soupy ambience that perpetuates through all the levels, through everything the player does,” de Quidt tells me.

Again, it all comes back to a sensual feel that pours out of the fabric of videogames, and it’s this that comes across in the words de Quidt uses in Veracity & Purpose.

“The level of detail is initially quite extraordinary. You can make out the lace on the sister’s bodice, the small studs on one of the dog’s collars,” reads a typical line from the game.

De Quidt is inspired by authors such as John Steinbeck for his prose on beauty and humanity, Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino for their “repeated ideas of spaces” that are important in a lot of level design in games. “I’m fascinated by picture books and guide books and ephemera, and I love how those authors play with those media,” de Quidt says. Unsurprisingly, Castles in the Sky could quite easily fit into the category of an interactive picture book, and we already know that Veracity & Purpose is intended as a fictional guide book. These are de Quidt’s attempts to emulate this merging of media forms that he so admires.

///

“Andrew Bird recently released an album called Things Are Really Great Here, Sort Of, in which he re-arranges and performs songs by The Handsome Family. There’s a song on it called ‘Tin Foiled’ that I’ve been listening to a lot recently, and it evokes a sort of pleasing mundanity/everyday feel while still having really evocative, strange imagery.”

///

For all his fascination and enthusiasm for these works, de Quidt struggles to pin down quite what it is that grabs him. I press him, and he tries to explain it as best he can: “I love the idea that the things that we leave behind, the things we discard as useless, are very telling about ourselves and the society we live in. Gone Home demonstrated this really beautifully, although even then the documents were direct letters and notes from one character to another. We can learn a lot from a calendar, or a form half filled in, or the arrangement of books on someone’s desk. If we knew that our culture was crumbling or was vanishing, sure, at first we’d grab records of ourselves and our cities. I think it’d only be a matter of time, though, before we were including postcards, cereal box commercials, little books of stamps.”

This attention to what de Quidt goes on to call “fiddly detail” that reveals the “real beauty in mundanity” strikes me as being similar to the laborious processes that Stanley Kubrick went through when researching for a film he intended to make. Recently, I watched Jon Ronson’s documentary Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes, which is about the thousands of boxes that Kubrick mounted up full of research—location photos, screen tests, notes to his assistant—kept in complete and delicate order as alphabetical files. It’s revealed in the documentary that for his last film, Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick had asked for photographs of “the detritus of people’s lives.” He got very excited about what objects were placed together and how they were arranged on bedside tables, atop dressers, and sprawled across lone chairs in the corners of rooms, exclaiming that no art director could ever come up with how bizarre it all was.

De Quidt draws the lines more directly still: “Mundanity is where most of us live our lives. My life is almost always mundane. It’s not necessarily an unpleasant place to be, but it fascinates me exploring and revelling in the sort of quiet stories that mundanity and its trappings can bring.”

De Quidt’s approach is a highly unusual one in videogames, or in any creative industry, really. It’s the opposite of what those with the money want to be made, or are willing to take a risk on. They want it quick, fast, and by the numbers. We’re rushed through areas by waypoints and checklists in most videogames. But what de Quidt talks about is an elegance and slowness; giving people time to take in the virtual spaces and the objects kept inside. This allows for an atmosphere to emerge in the virtual air by engaging all your senses in this one drawn-out moment. Kubrick and de Quidt aren’t the only artists that take this approach, and those that do have their creations speak in this esoteric language are among my favorites.

///

“I’m re-reading Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino at the moment, a series of descriptions of fictional cities, as told by Marco Polo to Kublai Khan. They’re very short, barely a page apiece, but the amount of world building and beauty and strangeness and normalcy packed into each one is stunning.”

///

J.G. Ballard, especially in Crash, stops time and zooms in on every visual grotesquerie of bloodied car crashes and the feelings they arouse in James Ballard. The beginning of Ridley Scott’s Alien has us pan slowly across the workspaces of space engineers and all their throw-away decoration as the silence of the Nostromo is disturbed by its waking passengers. Practically everything that Andrei Tarkovsky ever made tells its story through the way the wind blows through the grass, the curves of snowfall on the ground, or how water drips down from a rooftop; the contours and behaviour of the surroundings are just as big as the characters on screen. Zdzis?aw Beksi?ski was incessant in how he drew decaying biology, hellish flesh, gaunt and dusty skeletons with such terrifying empathy. I’d even allow similar credit to the simultaneous multiplicity and minuteness of the world-building in BioShock Infinite, before you get a gun in your hands. Although, if a videogame example is to be used here, the rough and up-close textures of early 3D games have a more overbearing presence than anything since them.

In all of these media, we’re encouraged to dwell on minutiae, to scrutinize and acquire the feel of a place through long shots or extensive passages of detailed text. It’s this that de Quidt brings to his videogames. I’m not saying he’s the next Kubrick, but that he is one of the few who speaks this rare artist’s language that transcends mediums, as he’s proving by bringing it to videogames. He’s not the only one either: it’s exciting for me to see it appear in shades elsewhere in videogames, in the textures of garments in The Witcher, in the blowing sands of Journey, and the corpse water walls of Dark Souls. It’s an idea and an aesthetic that fits the lurid and attentive interaction that videogames allow for especially well.