You could very easily dismiss The Magic Circle as too “niche” after hearing its premise. As a videogame about an unfinished videogame, set in a world where your only weapon is videogame development, I can see why some might just start tuning out.

But you’d be missing a Halley’s Comet of interactive stories if you did—one of those rare and almost mystical instances where a videogame actually speaks to the lives of real people. Not superbeings, cyborgs, or impossibly cute anthropomorphic animals, but human beings with flaws and contradictions. Because while, technically, The Magic Circle is about a broken videogame, the crux of its tension lies in the brokenness of its creators—and the industry that spit them all out.

As ex-Irrational and Arkane Studios veterans, the four-person team behind The Magic Circle have an intimate understanding of what the words “development hell” mean. And while a dark, satirical comedy about their past experiences might sound like an excuse to air petulant professional grievances, their intentions come from a much more reasonable place.

“It’s true that living through five or six collective decades of AAA work lead to our desire to express some of those experiences,” Jordan Thomas, designer and writer, explains. “I guess the idea of being an entity in a game world while we, the designers, made terrible decisions about it from the sky just always struck me as a joke worth telling.”

Lead artist Stephen Alexander agrees that “this certainly isn’t about our resentment or a parody of a particularly bad experience we’ve had. These are introspective jokes, where we laugh at ourselves and all the mistakes we’ve made—will keep making. We’ll be the first to admit that, hey, we had to get a game done too. We made mistakes, cut corners. You could call us hypocrites. But this is what we’ve internalized about the development process, an expression of our own faults. And hopefully, there’s some universality in that.”

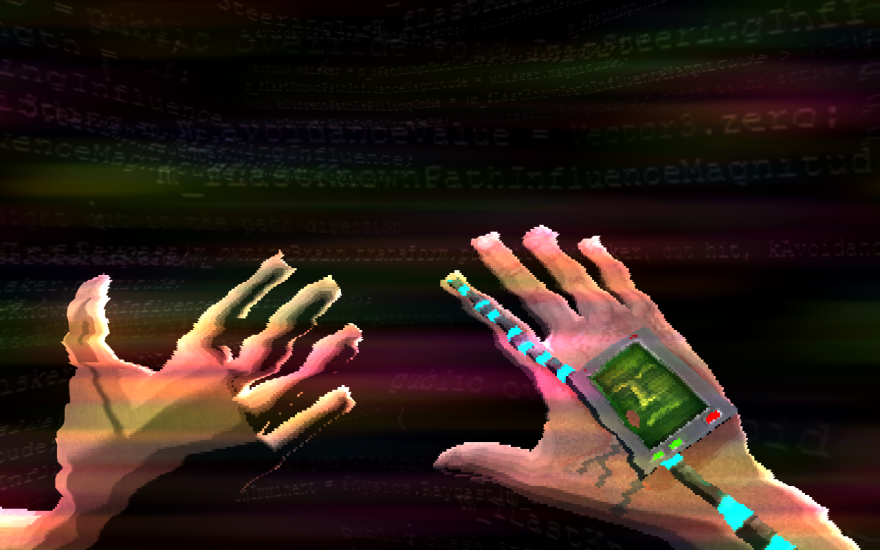

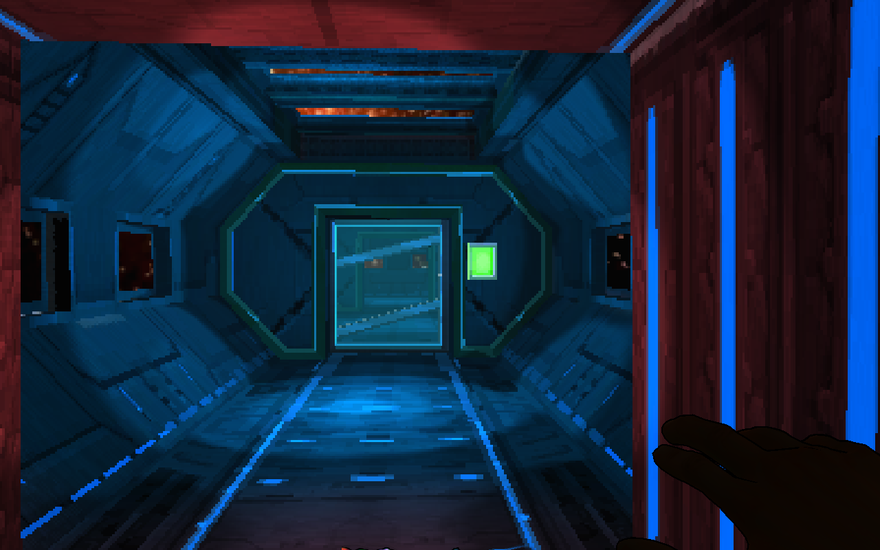

Recently released on Steam Early Access, The Magic Circle drops players into a videogame that’s fighting to gain control over its own world by wrestling power out of the hands of their game gods. As the player (or “playtester”), its up to you to get through the dilapidated virtual world crumbling with glitches by hacking into the game’s own systems, and altering the behaviors of enemies and objects to solve puzzles.

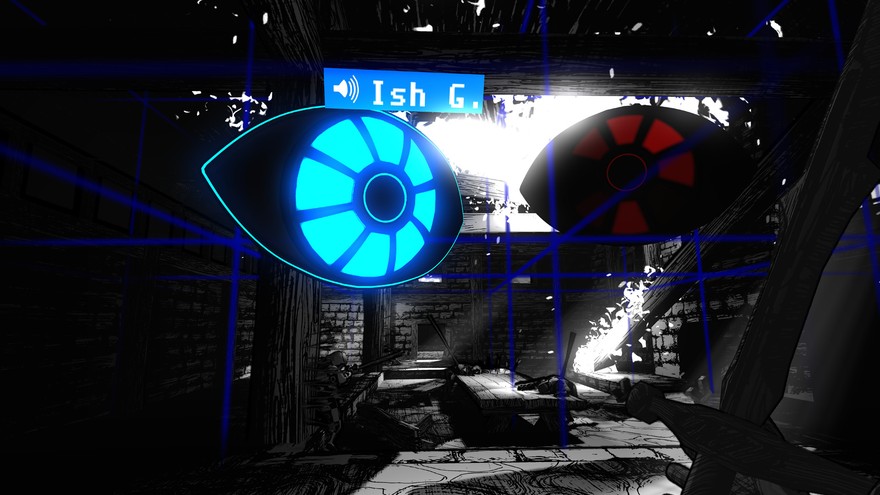

The two bickering lead developers responsible for this Frankenstein’s monster narrate throughout the game, their clashing visions causing most of the dramatic tension. And while its true that both developers seem to embody polarities of the game designer spectrum—with one, Ish, being an egomaniacal writer hell bent on making his narrative central, and the other, Maze, a pragmatic systems-person who thinks cutscenes are garbage—their characters never cross the line into caricature.

“As a writer, I just tried to make sure every character stayed true to some voice I had inside my own head at some point,” Jordan says. So while their philosophies oscillate between neat polarities, each of their individual foibles remains grounded and specific.

“For us, a big part of this project is trying to show that the people who make your games are…well, just people,” Stephen says. Most of us probably remember that moment while growing up, when you realized these enormous, magical, expansive worlds we loved so much were actually created by regular human beings. Kain Shin, the third member of Question and designated “tech guy” on The Magic Circle, says, “I still sometimes struggle with seeing my game developer heroes as people, actually. It lingers to this day.”

Because when we’re not disregarding the human beings who created our game world altogether, we’re idolizing the individuals we mythologize into to videogame-making demigods. “I bought into the game god thing for so long,” Jordan admits. “As a kid I’d think, ‘Oh! That one person must have shat this thing out of their head whole!’ Now, after seeing what it’s actually like, we wanted to explore the notion that these gods we worship have always had feet of clay.”

But more than just an exploration of the game developer as human being, The Magic Circle helps bring some of humanity back to being a player in itself. Rather than acts of destruction, The Magic Circle‘s system-based gameplay requires you to engage in an act of creation in order to “defeat” enemies. To progress, you must alter and remake rather than search and destroy. As Stephen points out, “there are already so many Let’s Play videos of people purposefully circumventing designer-built walls. So it just made sense to leverage the systems in our story, since its a game all about that in the first place. It felt right: to reduce limits and bring down those barriers as much as possible.”

“For me personally,” Kain continues, “there’s just very little difference between a super-fan and game developer, a lot of the times. You create something together. And working on this game felt like a way to bridge that gap and, at the end of the day, say: we’re all just people. We’re flawed, and make flawed things.”

As a modern twist on the mythic trickster-who-steals-fire-from-the-gods archetype, Jordan explains that “having a linear story, where players were asked to just passively accept power, would’ve been a broken metaphor. We needed to make it so that, overtime, you became better than the gods who had forsaken you and the game—not because I told you so in the script, but through the language of games itself.”

But it’s been an uphill battle, working on a game that satirizes the many open wounds that remain fresh for the industry at large. And while The Magic Circle doesn’t present itself as an answer to the suffering rampant in the game development process, the team describes the catharsis of expressing it as “therapeutic.”

Though all three of the Question team believe their game ends in a hopeful manner, they found it important not to shy away from any of the harsh realities that come with game development. “I think our game is an optimist, but with a boot knife,” Jordan says. “In the sense that there’s hope, but there’s a pretty strong note of realism, too. But, if you go through all of this, and come out the other side still wanting to make interactive stories, good for you, because we brought our best weapons to bear along the way.” Jordan smirks, while the others chuckle at this. “I guess the game just makes you go through hell, before you can start to imagine what a new heaven might look like.”

You can download The Magic Circle on Early Access for $19.99, on PC and Mac. The finished product (though very close to the Early Access build), is slated to come out in six weeks.