Killbox is a game about drone warfare; about the experience of killing, of dying, and of the yawning expanse between the people doing those two things. It’s also a collaboration between US-based activist Joseph DeLappe and Scotland-based game designers Malath Abbas, Tom Demajo and Albert Elwin—one they hope will leave its mark on the people who encounter it.

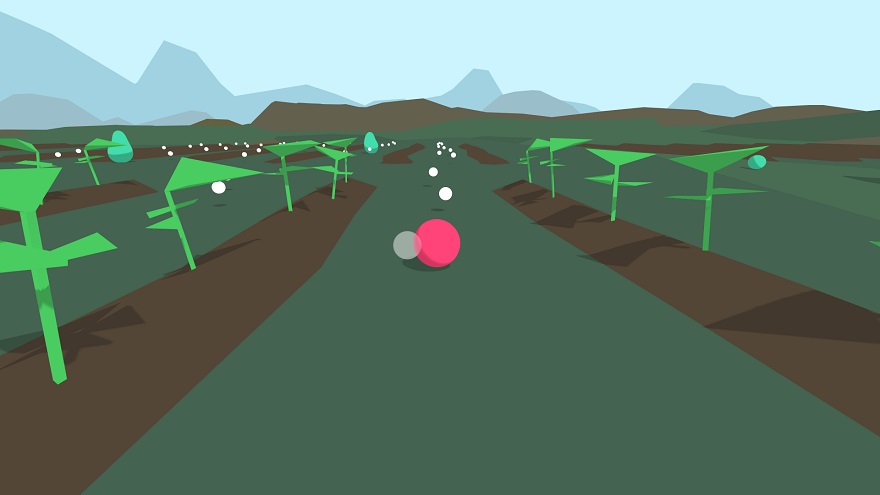

“At IndieCade we had a number of players cry once they realized the consequences of the in-game actions,” Abbas explained to me. Having played it I can see why. Killbox tries to get under your skin immediately, before you have time to put your emotional defenses up, before you have time to distance yourself from the subject like so many of us have. At first, the breezy controls of a pastel-colored sandbox caught me off guard, unraveling my cynicism. Later the chilling casualness of fragmented comms chatter filled me with dread, eventually breaking my heart.

Drone warfare is built on a series of sinister contradictions. The actual aircraft is unmanned, even as the number of people needed on the ground to support automated warfare swells. It’s most effective only on the weakest targets, requiring massive asymmetries in the military capabilities between those involved. And despite the people involved being thousands of miles apart, their interactions distorted and obscured by layers of technology, the drone strike itself is insidiously personal.

“The more research we carried out the more duality would come up as a key thread for me personally,” said Abbas. “I am fascinated by the human-to-human connection created through the physical and digital technology utilized in a drone strike: As a pilot presses the trigger this sends a physical signal that traverses the globe digitally and ultimately launches a chunk of explosive metal and technology that makes direct physical contact with another human being on the ground with devastating consequence.”

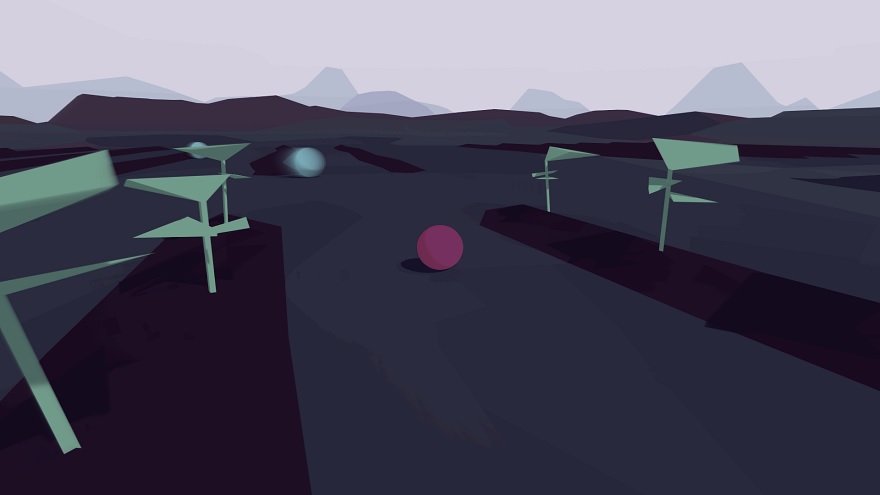

This led the team to focus on a multiplayer mode with one player hopping around a carefree, abstract space on the ground, and another analyzing data from above through a drone’s camera feed. As a result, the two come at these dualities from both ends, potentially recovering something from the wreckage in the middle. “From my perspective,” said DeLappe, “the hope is to create a visceral experience that utilizes the attractive nature of a game-based project to draw participants into what is truly a discomfiting experience.”

Killbox’s sound design is crucial to shaping how each player interacts with the game differently. The pilot has absolute power but no freedom, and the villager has absolute freedom, but no power. “The pilot is watching and listening through a technologically mediated experience and the villager is right there,” explained DeMajo. “We wanted the pilot to feel constrained and alert, and the villager to feel free and relaxed.”

The two experiences are connected by what DeMajo calls “parallel sonic threads,” however. “The ambient base for the pilot is a close and persistent machine hum, irregularly punctuated by distorted chatter and occasional machine beeps. From the villager’s perspective, there is the distant and unsettling sound of the drone itself, but this is punctuated by the birdsong and playful interactions.”

In “Phenomenology of a Drone Strike,” Nasser Hussain writes, “In the case of the drone strike footage, the lack of synchronic sound renders it a ghostly world in which the figures seem unalive, even before they are killed. The gaze hovers above in silence.” For the observer below, this relationship is inverted. “If drone operators can see but not hear the world below them, the exact opposite is true for people on the ground.” For residents of the areas targeted in Pakistan, the “low-grade, perpetual buzzing” has become synonymous with death from above, with the psychological terror that results well documented. Drones are “Mostly invisible to the people below them,” notes Hussain, “But they can be heard.”

In many ways, this is the relationship Killbox is trying to capture, one which grows out of encounters based around incompletes. “Killbox’s most dramatic juxtaposition, as far as sound is concerned, is the experience of the strike itself. The pilot hears nothing but sees everything,” said DeMajo. “For the villager on the ground, this is the loudest and scariest moment of their experience.”

What makes these contrasts so stark, however, also makes them tragically complimentary. “The pilot is inside a monophonic and monotonic soundstage that feels one dimensional and inescapable, whereas the villager is in a deep and expansive 360-degree sound space, offering freedom and encouraging exploration,” explained DeMajo. “For the pilot, the continuous and distorted voices make the player feel unable to claim their own personal space—the pilot is a voyeur visually, but in the sound domain it feels like they are being monitored themselves. The villager on the other hand is surrounded by natural and unthreatening sounds, and friendly noises are created by the player themselves as they interact with other characters.”

Killbox is a political project as much as an interactive installation, but whatever questions it asks, whatever activism it invites, are abstruse and free of righteous monologuing. Instead, it’s enough that the game, in Abbas’ words, “crosses and connects physical, cultural and virtual spaces.”

It’s an approach similar to the one taken by Paolo Pedercini and Jim Munroe for Unmanned, a 2012 project about a day in the life of a drone pilot. Players choose how to respond to their environment by crafting the thoughts in the protagonist’s head. “When we were making it the lack of gameplay consequences bothered me a bit,” said Munroe, “but after watching people hover over these choices and really consider them made me realize that just asking the question and getting people to answer was really the important thing.”

By adding a little bit of interactivity and coming at the question of drone warfare sideways, Unmanned proved engaging beyond the surface provocation of its conceit. “When an issue is already out there and extensively debated, artists and cultural producers should think about what they can bring to the table,” Pedercini added. “Way too many socially-engaged artists just ‘put a drone on it’, to paraphrase Portlandia, using the drone as an iconic, evocative, troubling readymade.”

Find out more about Killbox on its website.