When he turned it on the usual faint smell of negative ions surged from the power supply; he breathed in eagerly, already buoyed up. Then the cathode-ray tube glowed like an imitation, feeble TV image; a collage formed, made of apparently random colors, trails, and configurations which, until the handles were grasped, amounted to nothing. So, taking a deep breath to steady himself, he grasped the twin handles.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—Philip K Dick

///

In Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which inspired Blade Runner and so is one of the many mitochondrial Eves of all cyberpunk art, Mercerism is the religion du jour, designed for an age of simulation. In Mercerism people across (what is left of) the world are united through “empathy boxes”—consoles that link each individual to one single, shared experience. That experience is the Sisyphean climb of Wilbur Mercer up a mountain of dirt, pelted by stones from unseen attackers. Followers of Mercerism can share in the pain of each stone as it hits, the desperate crawl up the dirt slope and the feeling of being a single entity among a vast, displaced struggle. By becoming one with Mercer they also become linked with every other human who is, at that time, connected to their own empathy box, in their own apartment, in their own city, surrounded by the same post-apocalyptic wasteland. Empathy is the deciding human attribute, preach the followers of Mercerism, the one that will save us all in a world of inauthenticity.

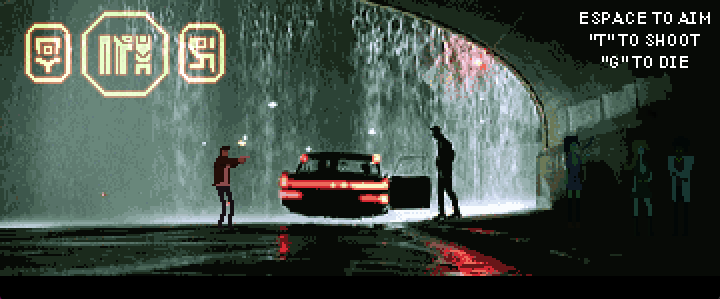

The Last Night is a videogame that is 120 seconds long and was made in 6 days. It was the winning entry of a cyberpunk game jam. In it you take control of a man as he performs the assassination of a target; you can take two minutes to play it here. It begins with its leather-jacketed, blue-jeaned hero arriving at a train station. The player walks this everyman to the right and he is greeted by another man who claims that the hero is late. It doesn’t matter how long you take to walk over to the man at the train station—he will always pronounce you late. You can idle as long as you want on the train platform, enjoying the ambient electro soundtrack, the sputtering rain and the pixel art backdrop. You can watch the cities’ citizens chat, and enjoy their 80s throwback clothes and even loose as many shots from your handgun into the back of their heads as you wish. They will just continue to smoke their cigarettes under flickering streetlights, the distant rumble of thunder preserving the rich atmosphere, as if the whole game was embalmed.

///

Despite being a central element of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Mercerism was excised from the film Blade Runner. Over its multiple drafts and rewrites, Blade Runner’s script slowly shed the artificial animals, the overt religious symbolism, the concept of kipple (a cover-all word for waste) from the book. The film instead focuses most of its screen time on the texture and colour of its cyberpunk world. Like many contemporary science-fiction films, this was a film made to immerse its audience in a new universe. This future vision is drawn so successfully that William Gibson, one of the fathers of cyberpunk, was afraid that readers would think he had stolen the aesthetic of his first novel, Neuromancer, from the film. It’s hard to imagine that now—watching Blade Runner today is an odd experience, the images it presents being both powerfully seductive and categorically used-up.

The Last Night lists Blade Runner among its headline influences. Mentioning the film (and its game adaptation) by name feels like a pointless gesture, especially in the case of a cyberpunk game jam—The Last Night is indebted absolutely to Ridley Scott’s landmark movie. The endless rainy night, the neon-drenched mega-city, the protagonist’s brown jacket: each image is carefully gathered from Blade Runner and its countless imitators. Cleaned up and kipple-free, The Last Night appears like the epitome of cyberpunk, efficiently boiled down into a couple of dense minutes. For a game played in a letterbox strip on a browser, it exerts a powerful hold on a player’s attention, the enforced slow walk giving a rhythmic cool to every action. This pace invites the player to linger in its crude pixel art world as if it was Ridley Scott’s Los Angeles, but without cinema’s ceaseless forward movement. Just as Blade Runner shed Mercerisim in its pursuit of atmosphere, The Last Night sheds the themes and symbols of cyberpunk in pursuit of moments of catharsis, carefully orchestrated through sound and image. Here technology presents no problems, only opportunities for the audience to disappear beneath its screen-thin surface.

///

But the dreams came on in the Japanese night like live wire voodoo and he’d cry for it, cry in his sleep, and wake alone in the dark, curled in his capsule in some coffin hotel, his hands clawed into the bedslab, temper foam bunched between his fingers, trying to reach the console that wasn’t there.

Neuromancer—William Gibson

William Gibson’s cyberpunk, despite appearances, is very different from Blade Runner. Like Philip K. Dick’s vision of Mercerisim as the religion for a world where technology’s presence comes hand-in-hand with God’s absence, Gibson’s cyberspace is the conduit for every undercurrent he observed in society. In Gibson’s Neuromancer, technology is a drug, a high, something to disappear into. In Neuromancer’s sequel, Count Zero, voodoo gods and goddesses have started appearing in cyberspace, the gap between artificial intelligence and omnipotence closed into a self-serving loop. Meanwhile the titular character’s mother disappears into virtual soap operas, barely existing in the real world at all. In Gibson’s work the reader is not the one being absorbed into the world, the characters are, struggling at the fringes of a society that resembles our own, their fantasies and dreams digitally connected to a system which is ruled by streams of money, power and corporate paranoia.

///

The world of The Last Night is a shallow one. In reality, playing the game is like jacking into a soap opera: it is cyberpunk as a series of disconnected cliches. Its transition from transport hub-to alley-to nightclub-to balcony is like a musical score, inevitable in its progression, but enticing in its familiarity. The similar rhythm of arrival, acquiring an objective and then executing that objective is perhaps even more recognizable for players, written as it is into almost every “cinematic” game of the past 5 years. The result is satisfying, each gesture and action huge and significant, the game empowering the player to be Harrison Ford himself. The Last Night, like the “sit down and shut up” cinema of Blade Runner, is an exercise in the enjoyment of doing what you are told. The game’s world is seductive because it is dissimilar to our own. It is impossible to escape into a world that is a constant reminder of the compromises, corruptions and crossed wires of our real lives. The Last Night may only be a two-minute escape, but, like choosing not to shoot the hinges in Call of Duty: Black Ops, idle a little and the timescale of the game suddenly stretches out. This is a city you can live inside, basking in the neon and the rain, slipping into the fantasy. On the final balcony, before taking your last shot and lighting up your consummating cigarette, you can spend a lifetime standing opposite your target, looking out at a sky the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.

Cyberpunk has been pronounced dead many times over. One of the central figures of the movement, Bruce Sterling, made the claim as early as 1985, before Count Zero had even been published. These pronouncements have come as often as Blade Runner re-cuts, and in some ways have been just as unconvincing in their finality. The imagery of cyberpunk may appear more often in the form of parody and pastiche, but its reimaging of science fiction as a method to observe and anatomize societies has lost none of its potency. Gibson is perhaps the most successful in this regard—he observed society rather than technology, and filled in the gaps beneath the obsessions and between the power-structures with cyberspace. His relevance is a matter of content, not of style. Call me paranoid, but don’t we too exchange our human vulnerabilities with systems of terrifying ubiquity? Don’t we find ourselves addicted to unreal experiences, escaping through the ethernet cable of least resistance?

///

The Last Night is cyberpunk as a museum piece, cleaned up for modern consumption. As the winning entry of the 2014 cyberpunk game jam it is a telling artifact of a denatured genre, and as a game it is an equally strong evocation of the rise of the cinematic, immersive experience—but it is in the combination of the two that it feels particularly timely. Unknowingly, its creators have, in six frantic days of game-making, presented a manifesto for one of the great dead ends of game design. Cyberpunk has the potential to be one of the most important influences on videogames. It presents worlds that are hypnotic to enter into, and yet cut-through with a radical view of the society that surrounds them. Yet in The Last Night cyberpunk is just noir with a palette swap—the same old story of a man with a gun who has to kill another man. Apart from its hard-man walk, the only other action the game presents the player with is kill. This design vocabulary shares the same sense of constriction with its aesthetic vocabulary, strong-arming you into believing in the game and your agency within it. The Last Night is not a bad game, it just displays the symptoms of a genre that has lost its way. Like the lifeless future that Blade Runner’s perfectly sculpted aesthetic eventually led cyberpunk into, The Last Night’s only future vision is not one of mega-cities and wastelands, but of hollow experiences masquerading as being vital.

The TV set continued, “The ‘moon’ is painted; in the enlargements, one of which you see now on your screen, brushstrokes show. And there is even some evidence that the scraggly weeds and dismal, sterile soil—perhaps even the stones hurled at Mercer by unseen alleged parties—are equally faked. It is quite possible in fact that the ‘stones’ are made of soft plastic, causing no authentic wounds.”

“In other words,” Buster Friendly broke in, “Wilbur Mercer is not suffering at all.”

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—Philip K Dick

///

Of course, Mercerism turns out to be a hoax, a fake. The footage of Mercer climbing the hill of dirt was shot in an LA studio backlot, the role of the hero being played by an old drunkard. This short bit of footage is endlessly looped for its captured audience, plastic rocks causing them simulated pain that the man climbing the mountain never felt. For us, reading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? almost half a century after it was written, this barely registers as a revelation. Our “empathy boxes” have never been pointed at a real destination, only towards the age of simulation. Like cyberpunk’s many consoles and interfaces, our equipment of choice allows connections and disconnection in equal measure. It’s difficult to say which the followers of Mercer were truly experiencing in their climbs. Seen from the outside they were committing ever more time to a pointless task, scaling an endless hill of dirt that, ultimately, was never even real. Yet each individual, firmly gripping the handles of their console, walked among the others, sharing in their distant thoughts and feelings. In the end all that can be said for sure is that they were human, and that they felt something.