It begins with the blankie. Mother isn’t able to comfort you all day every day, and your developing brain is rapidly attuning to that fact. But you also aren’t able to comfort yourself, not yet, not entirely; the feelings are too strong, language and notions of cause-and-effect relationships too nascent. And so the blankie.

It is, by all accounts, an ordinary blankie. But in your tiny hands it possesses a special power, one that until now has been the exclusive purview of your mother, which is the power to comfort. Of course, even your young and elastic mind can appreciate that this blanket is not really your mother, and that it’s not really alive. Yet it’s not not alive, because you have given it life. When you’re scared, the blankie soothes you. When it’s accidentally left behind at a restaurant, you go into conniptions. The blankie grants safety—hence the phrase “security blanket”—but even more important is the source of that safety: by imbuing a mundane object with humanity, you have built a bridge between the outer world, where your mother lives, and the inner world where you alone reside. This is what psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott recognized when he identified the blankie as one instantiation of a much broader phenomenon that he called “transitional objects.”

Early transitional objects, be they blankets or teddy bears or imaginary friends, are private. They hold great power in the eyes of their creators but appear ordinary to everyone else. These objects often take on primary emotional functions: they calm when scared, soothe when upset. As time goes on, however, we begin to share our transitional objects, and their purposes become more varied and nuanced.

Consider the following: Two children are in a park, running around. One picks up a small stick and says to the other, “I am an evil wizard. This is my magic wand and I cast a freeze spell on you.” Without missing a beat, the second child stops motionless in her tracks.

How do we understand such an extraordinary turn of events, which in fact is the kind of typical play behavior anyone who spends time with children will see on a daily basis? The stick is not a magic wand, it’s a stick. But one child has decided to bring it to life and, in turn, grant her the ability to control others. Even more remarkably, the second child chooses to see what the first child sees, and allows herself to be controlled. They are sharing a transitional object, but between what and what are they transitioning?

In infancy, the blanket serves to move the child from being comforted by the mother to being comforted by the self. The children in the park, on the other hand, are transitioning deeper existential notions into their conception of self, trying on powerful feelings for size within a safe and temporary playspace. Together they can explore what it’s like to be strong and weak, sadistic and kind, good and evil. Most likely after a few minutes, the roles will switch: the first child will hand the stick to the second and say, “Okay, you be the evil wizard now.”

Our capacity to animate the inanimate is, according to Winnicott, one of the foundations of play, and play is the activity that rests at the core of human socialization and creativity. The use of objects to safely explore overwhelming aspects of living is relevant throughout the lifespan, and can help us to understand why play remains important to us into and throughout adulthood, even as the nature of play can take on subtler or more unexpected forms. We explore with issues of aggression and mastery through trying to make a ball go through a hoop. We view the world through one another’s eyes by debating what a bronze sculpture “means.” And sometimes, as reported by The New York Times, six million teenagers start flipping plastic water bottles and going absolutely berserk.

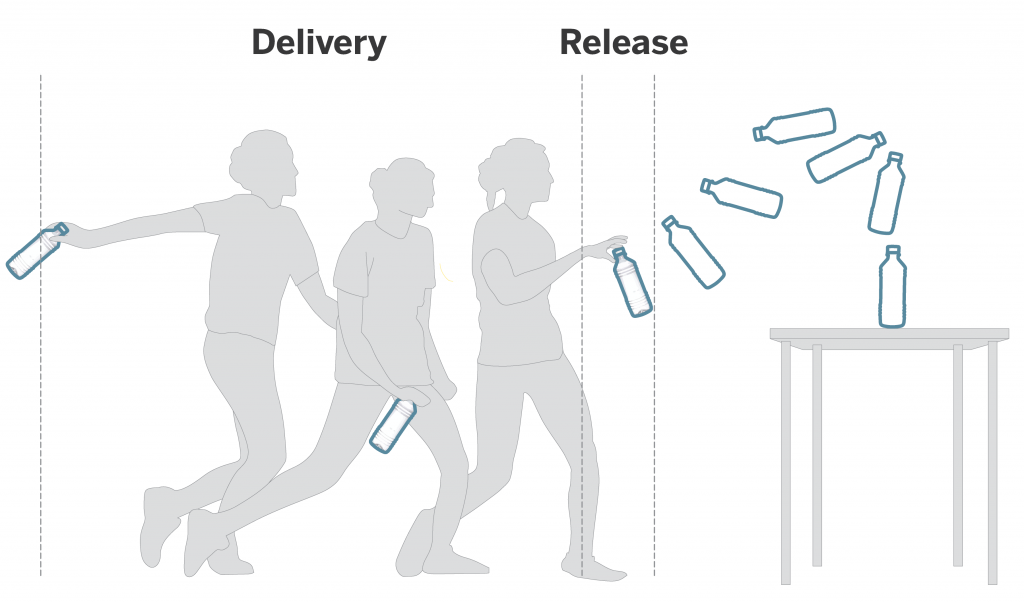

The Times piece presents this “craze” predominantly as an annoyance for parents, something they do not understand. Here is the transitional object at work, the animus that only some can see. To the average grown-up, it’s just a water bottle: it crinkles when their child grabs it, sloshes as it’s tossed in the air, and clunks as it lands (hopefully) right-side up on the table. In short order this sound loop becomes extremely irritating because, to the parents, it is meaningless: crinkle-slosh-clunk over and over for no reason, like a form of torture.

Play is wholly a matter of perception: for it to work, participants must agree that they all see the same thing. If someone breaks the illusion, transitional objects lose their vitality and play is spoiled. Say you were to go up to those kids in the park and shout, “Hey stupid, that’s just a stick!” In effect, you would be forcing them to either justify their version of reality, creating a split between your subjectivity and their own, or abandon the object entirely and quit their game. (Note: please don’t yell at children.) While younger kids are likely to become overwhelmed under such pressure, adolescents are at a developmental stage marked by the transition from childhood to adulthood, and so rebellion against the perceptions of authority figures can be regarded as most welcome. The baby thinks, “This blanket has some of my parents in it” and feels safe; the teen thinks, “This water bottle has none of my parents in it” and feels liberated.

The virality of social media has upended any notions of playspace that Winnicott might have predicted in his mid-20th century heyday: one high schooler bottle-flipping in North Carolina can energize peers the world over. “It makes you feel accomplished,” said a teen named Alex in the Times piece, which (pardon the pun) holds water: notions of accomplishment and success are exactly what we would expect a 17-year-old on the precipice of social and legal independence to project onto a transitional object.

But flipping bottles also, I would imagine, makes Alex feel connected. He may be doing so alone at his kitchen table, but on some level he knows countless others are doing the same thing at the same time, near and far. His water bottle is just one instantiation of the communal water bottle being flipped, which makes him part of a monumental play experience that links him to his peers, and sets him in juxtaposition to his mom who just doesn’t get it.

The “craze” is so-called by adults, because they don’t understand and see the pastime as mindless. But there’s nothing crazed about it. In fact, bottle-flipping teens are demonstrating to all of us the unique powers of the transitional object: its capacity to defy time and space, and transform even the most ordinary thing into an expression of one of the deepest human drives, the drive to play together.