Lucas Pope teased his Papers, Please follow-up Return of the Obra Dinn back in May, with little more than a GIF and some sparse hints to illuminate exactly what this game would be.

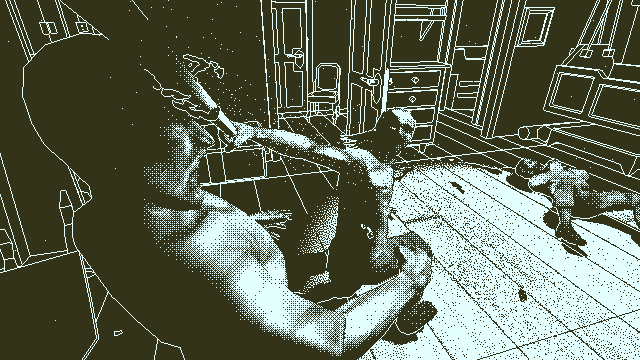

But today Pope released the first build of Obra Dinn for free. It’s a ten-minute slice of the game that reveals its central interactive hook, and how surprisingly well the whole “1 bit rendering” thing works in motion.

You’re an East India Company insurance adjuster aboard the ghost ship Obra Dinn, and you have to find the captain’s logbook. However, despite the workaday throughline with previous Pope protagonists like “immigration inspector” and “surveillance operator,” he told me that “the insurance adjuster part of Obra Dinn is honestly pretty thin. I guess I just like building mechanics from mundane tasks, and then using those to construct a narrative.”

That fascination with tedium is the hallmark of Lucas Pope’s work. And lest that sound pejorative, consider that nitty-gritty fetishism is what colors the work of, say, David Fincher and Flying Lotus. Not a bad group to find oneself in. Pope’s procedural predilictions made Papers, Please a ludic peer to the aforementioned artists, throwing the player into a richly-realized world whose moral complexities gradually revealed their terrible contours.

And, if he has his way, Return of the Obra Dinn will be a completely different game. Where Papers, Please was ripe with sociopolitical subtext, Pope says that there’s no larger idea he’s angling for with Obra Dinn: “It would be nice if something larger grows out of it—this is what happened with Papers, Please—but it’s not a consideration at the moment.”

Instead, Obra Dinn is a straightahead mystery. Strewn about the ghost ship are skeletons, and using a magical pocketwatch you can bear witness to each character’s final moments in order to fill out the logbook with their causes of death.

It’s immediately gripping. The unique black/gray visuals, the shockingly great voice acting, and the delightful decision to have your first-person avatar’s hand extend toward usable objects—in lieu of a “use” prompt—give it serious heft.

As for the paradoxically vivid death-tableaux that accompany each flashback—a pistol suicide caught in an instant of bursting blood, a cold body in a bunk—Pope intends only for the player to bear witness. “The death moments will be strictly non-interactive. You’ll have no control over the past and no power to affect anything—just passing through to take a few notes. I like the simplicity of that kind of rule.”

Simplicity does seem to be Obra Dinn‘s remit, but that’s not to say the full picture of what happened to the vessel and her crew will be a cinch to put together. “Some identities will be obvious or given easily and others will be much more difficult to suss out,” Pope said. “For example, of the characters in the demo, you won’t find out who one of them is until near the very end of the game. So the challenge is remembering how this guy died when you finally figure out who he is.”

Somewhat lost in the (rightful) exhortations of Papers, Please‘s ethical torsion was how dang fun that game is. It moves with real momentum, all its parts aligned toward the same ends. Return of the Obra Dinn strips away the meat until all that’s left is the skeleton: people meeting sad, violent, triumphant, outrageous ends, and you as the working stiff pulling at the strands until the whole thing unravels. It puts the burden directly on you with as little mechanical density as possible. The Company’s counting on you to return accurate figures.